Last week, Michael Gilson, the former editor of, among others, the Belfast Telegraph and The Scotsman, wrote in Press Gazette that financial support for UK local news should be directed to smaller publishers rather than the large legacy players.

Now David Higgerson, chief digital publisher at Reach, argues that staying relevant for the majority of readers is a far more pressing issue for local media than debate over ownership models.

It’s an argument almost as old as the internet itself: local journalism would be fine if it wasn’t for those big corporate firms buying them all up.

The publication of Enders’ recent state-of-the-nation report into local journalism in the UK was always going to bring this argument up again, because it’s brilliantly simple in logic – but also utterly flawed upon closer inspection.

Michael Gilson, the former editor of the Belfast Telegraph, Scotsman and Brighton Argus, was a vocal proponent of this argument in his article in Press Gazette. As a journalist, it was fascinating to read. Who wouldn’t want a world where public interest journalism was produced in abundance, with funding secured for every significant public figure to be held to account on every decision he or she took?

Sadly, the answer to that question often is: the general public. There is precious little evidence that the public at large are actively pursuing public interest journalism, on a scale and frequency which would sustain it on its own for the long-term. Which is absolutely not to say they don’t value it or need it, or that publishers shouldn’t make it a priority, but it would be false to say that the average consumer is knocking down anyone’s door for it every day.

Despite these admittedly hard-to-swallow truths, many hopeful media commenters, Miichael among them, persist in believing that it’s only a matter of time before the public “corrects” its view of local journalism and hankers for it again.

But hope won’t secure the future of local journalism. Dealing with reality head on, will. We’ve been here before, when our industry saw a proliferation of King Canutes convinced that online news consumption could never replace the printed paper. It did, yet still the chorus of “it was better in my day” continues to hum through many debates. Better for who? Certainly not the reader.

The flip from print to digital broke the bundled model of content which had served us so well for generations. By us, I mean journalists. We realised it hadn’t served the reader so well when, by and large, newspaper circulations fell and repeated efforts to set up paywalls around bundled packages of stories failed online. It was then that the need to drive a profit margin began to drive innovation, the need to show revenue improvements forced change to realign with readers.

The higher purpose of journalism had to become entwined with the business necessity of, well, staying in business. And that happened right in the heart of the newsroom. No longer was bringing in the cash somebody else’s problem.

Today’s local journalists ‘know their audiences better than any to have gone before’

Painting local journalists working in large media organisations as a gang of somehow hapless unfortunates locked up against their will, as is often suggested by those who no longer work in newsrooms, or never have, does those who do work in our industry a huge disservice. The current generation of reporters and editors know their audiences better than any to have gone before them. We may not always like what we hear when audiences tell us what they want, but ignoring them is not an option.

Local journalism needs to be – as it always has been – about far more than the public interest journalism that often takes the spotlight in debates about the future of local journalism. Public interest journalism is, of course, essential. And it’s most potent when it is widely read too. But we shouldn’t underplay the role local journalism needs to play in delivering breaking news, providing local, reliable information, and helping people live their lives. Just as local journalism always has.

The real challenge that all of us in local journalism face isn’t ownership structure, it’s the need to find that new role in people’s 21st century lives. It can be achieved, as many of the titles owned by big companies have shown.

In a 24-hour, always-on world, we need a local media which is near-enough always on, ready to inform, involve and inspire people about their local communities, and their daily lives.

If we want to have a serious debate about local news, we need to start with the aim of understanding how we find a place in the lives of as many people as possible – not just those with a passion for local news, or those who can afford to pay for local journalism, or worse still, those with a vested interest in local journalism remaining just so.

Local journalism debate should be about its role in our lives, not who runs it

The debate around local journalism shouldn’t be about who runs it, but the role it needs to find for itself in daily life in the 2020s. Print vs digital (how about let the reader decide), free vs subscription (why not a bit of both), high brow vs mass market (actually, lots of the titles I work with show that it’s possible to do both) are all examples of debates our industry loves to indulge in, but are based on the reader as a means to an end, rather than being treated as our reason for being.

Frequently, it is argued that big companies owning news brands are guilty of short-termism. But they also happen to be the companies which have continued investing in local journalism. There are many, many easier ways to turn a profit than to invest in news every year, yet they still do.

They are also the companies which have kept alive the titles which were once owned by smaller publishers. Companies which were historically happier to tolerate thinner margins as classified advertising moved to new online homes have, in many cases, been sold. CN Group in Cumbria for example, or North Wales Media, the Romanes Group, even the Rotherham Advertiser recently. Were it not for the investment of Lord Iliffe, where would the Stratford Herald, the Newbury Weekly News or several newspapers in Scotland be?

Let’s imagine a world where big corporates disappear. Who would fund journalism locally then?

What could other alternatives be? Something involving university journalism departments is one idea, but who is that really serving? A demand from local people or a university’s need to shift £9k a year journalism courses? Blind trusts funded by well-meaning local authorities? I’m sure there are some in public authorities who’d support that – but my council is struggling to afford to empty the bins at the moment, let alone underwrite accountability journalism. I struggle to see a time where any politician will argue putting money to one side for local journalism.

Or are we relying on the old argument of “the reader must pay?” Must they? A decade of evidence shows that, in the UK, and in the main, they won’t. Some will, some can. But local journalism as a luxury for those who can afford it feels like a backward step to me.

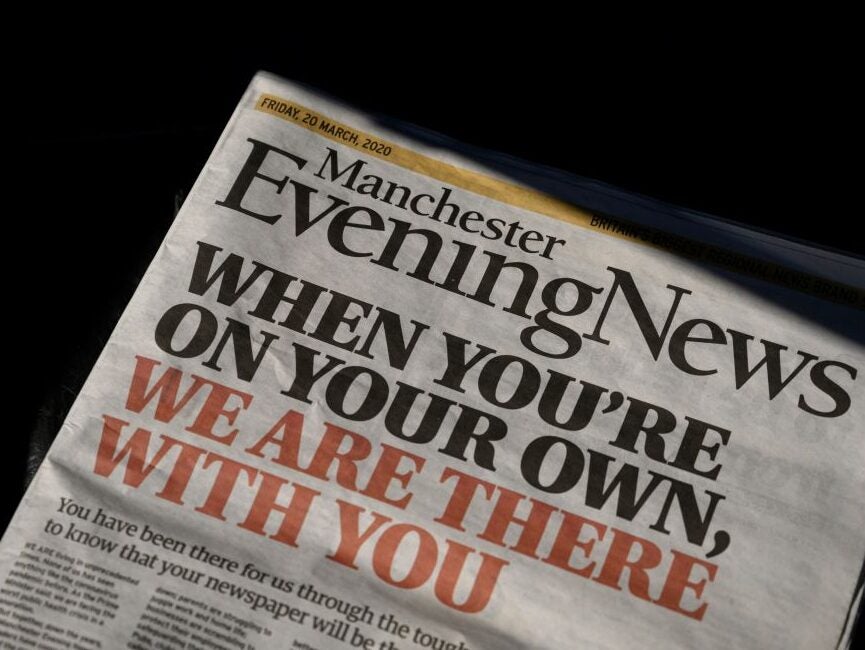

The ability of the Manchester Evening News to round up 170,000 signatures and change housing laws after uncovering the scandal of Awaab Ishak’s death in a matter of months shouldn’t be taken for granted. Telling people they have to pay for that doesn’t wash.

Local journalism needs to be more outward looking, and ask itself why it doesn’t look more like the communities it serves. Answer that question with positive actions and a huge leap towards being more relevant to more people can be achieved. We need to avoid financial blockers – be that university-only routes into journalism or insisting you must pay to be informed – that will serve only to weaken local journalism, at a time when information is so freely available elsewhere.

The reality is that so much of the other information available doesn’t come with the research and commitment to accuracy that stories produced from professional, regulated, newsrooms do.

Locking local journalism away from people who can’t afford to pay for it, and failing to remove the financial blockers which prevent many from even considering a career in journalism, will ultimately turn local journalism into a plaything for those with the cash to indulge in it. It might work for some, but it won’t work for most readers, and it kills what local journalism can do at its best.

Living as part of a large organisation, a local news title has to face the facts its prospective readers shares with it: what they want, how they want it, and how they’ll pay for it. It also has many upsides – the strength of a large company to fend off attacks to journalism, for example, or salaries which generally out-pace those of smaller operations, a point drawn out at last summer’s DCMS hearings into local journalism.

A commitment to diversity and welcoming all cultures is another, the chance to train and progress, various HR-related support if and when required. Most of these are taken as expected in a large organisation, and rightly so.

Reward companies investing in journalism – not tech platforms

I’m not here to argue for big companies vs small ones – I firmly believe you need both, and the more local journalism, the better. It’s one of the reasons I was so keen for Reach to play a part in the local democracy reporting scheme – the reporters housed with us produce stories which are used way beyond our titles, but only made possible by the collective efforts of our newsrooms to make sure safe, trustworthy public interest journalism is produced.

Whenever I see someone setting up a local news operation, I hope they will succeed. Whether it’s my own personal cup of tea is not the point – if an audience is well-served by an outlet, that’s a good thing.

There are many, many more hyperlocal and independent titles than there were a decade ago. It’s inspiring to listen to people who launched titles like the West Leeds Dispatch, the Bedford Independent, the Armargh I and Social Spider’s titles in London, and I admire and respect the great work done by Richard Osley and his team at the Camden New Journal, which blazed a trail 40 years ago. And, of course, the many hyperlocal and small-band operations which exist as part-time endeavours, attempting to fill a void.

There is also a simple solution to sustaining publishers big and small.

It’s this: reward the people who invest in content creation in the first place. It’s what used to happen, but as the tech platforms have taken hold of people’s attention, they’ve taken the revenue too. The distributors keep the cash on the back of the efforts of the creators. The government can solve that at a stroke, benefitting publishers big and small.

Simply put, there’s enough advertising to go around to sustain free-to-air local journalism in a way which keeps shareholders, journalists and readers happy. But as we’ve seen in Canada, the tech platforms are very keen for that never to become the norm.

When we’ve had the chance, we’ve invested heavily in local journalism at Reach. This year has been brutal but we continue to have more local journalists than we did in 2019. Of course, I want us to have even more journalists in the future, but to do that, we need to find a way to sustain their roles.

It’s easy to paint a gloomy picture about digital local journalism in the UK. It’s arguably desirable for some to do so. (Ironically, I was once told it drove clicks). But let’s not kid ourselves that the solution is as simple as waving goodbye to the very organisations which employ most of the UK’s local journalists. Hope won’t save the day, but listening to readers will.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog