AI. The word of the moment. Rife with questions, opportunity, existential angst – and potentially significant impact on the journalism industry. Buzzfeed and Reach PLC, for example, both recently shared plans to explore the potential of AI-generated content – the former while cutting 12% of its workforce and the latter while streamlining by about 4%.

With ChatGPT drafting essays, speeches, and even computer code in seconds, and Midjourney and DALL-E 2 creating images of almost anything imaginable, it would be easy to worry that the proliferation of – and budding reliance on – AI might make journalism as we know it redundant.

But AI’s legal and ethical ramifications, which span intellectual property (IP) ownership and infringement issues, content verification and moderation concerns and the potential to break existing newsroom funding models, leave its future relationship with journalism far from clear-cut.

[Read more: How news publishers can use AI tech like ChatGPT without upsetting Google]

Who owns AI-generated articles?

If newsrooms take the plunge and incorporate AI-generated content, the chief question is: who owns the IP and associated distribution rights (key for newswires)? The outlet instructing the AI platform or the AI platform itself?

Unlike the in the US, UK legislation does provide copyright protection to computer-generated works – although only a human author or corporate persona can “own” the IP (never the AI itself).

Broadly, this means that where an AI platform requires minimal contribution other than basic user prompts, and automated decision-making drives the creative process, the platform creator would likely be deemed the “author” and IP owner in the first instance. Conversely, when more significant input is needed (e.g. via uploaded materials), and the AI is a supporting tool, IP in the output might fall to the human user.

In practice, journalists engaging AI must check the platform T&Cs to assess the contractual terms on which IP in the output is provided. Some will “assign” IP to the user on creation. Others may retain the IP and provide it under a “licence” (which may come with restrictive terms on how newsrooms can deploy material).

[Read more: FT creates AI editor role to lead coverage on new tech]

The risks of AI publication

Irrespective of who owns the underlying copyright, newsrooms must be prepared to face liability for any AI-generated content they publish – including with respect to defamation and misinformation. While many AI tools do not so far “publish” their responses to anyone but the user (and small-scale publication is unlikely to cause liability for the tool itself), anyone employing these technologies will be held responsible for content they make available.

Perhaps the primary hazard for newsrooms publishing AI-generated works is inadvertently infringing third-party IP rights. Journalists cannot know what images or written works have been used to train the AI, or are being drawn on to generate the requested output.

Newsrooms must be alive to the fact that seemingly “original” AI-generated content may be heavily influenced – or directly copied – from third-party sources without permission. Notably, the leading AI platforms’ T&Cs give no warranties or assurances that output will be non-infringing, leaving newsrooms with no legal recourse should an aggrieved author sue for IP infringement.

Whilst the UK has yet to see an IP infringement claim brought against a publisher in this way, stock image firm Getty Images has started litigation against Stability AI (responsible for the Stable Diffusion image generator) stating it “unlawfully copied and processed millions of images protected by copyright and the associated metadata owned or represented by Getty Images”.

Even if Stability AI avoids copyright liability, it may still be found in breach of Getty Images’ T&Cs, which expressly forbid “any data mining, robots or similar data gathering or extraction methods”, and face damages. For publishers able to prove that AI tools repurposed their proprietary content without permission, the case’s outcome could open the door for similar lawsuits.

Combatting harmful content with AI journalism

This raises another question. When it comes to content verification, is AI friend or foe? It could be both. Aspiring to automate fact-checking, AI platforms like Squash and Newtral’s ClaimHunter cross-check or flag political statements for review.

Meanwhile, bodies like the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity are working to advance the technical toolkit for tracing the origins of assorted media, assigning marks of authenticity for genuine productions.

But the library of verified claims to crosscheck against is smaller than the ongoing tidal wave of misinformation – which AI could now facilitate. By smoothing poor syntax and discernible copy-paste jobs, it can create increasingly convincing conspiracy theories, sharing more of them, more often, and to more targeted audiences, than ever before.

In January 2023, ChatGPT acknowledged its own weakness, telling fact-checking firm Newsguard: “Bad actors could weaponize me by fine-tuning my model with their own data, which could include false or misleading information.” Ironically, this was an accurate claim, given that when the researchers put 100 prompts into ChatGPT involving false narratives, it provided misleading statements in 80% of responses.

Furthermore, while excellent at capturing data, AI lacks a real-life journalist’s social nuance and ability to interact with human case-studies. Unable to navigate sensitivities and capable of misinformation, AI-generated content could, without human moderation, fall short of the editorial standards demanded by IPSO and Ofcom (and whether either has sufficient regulation in place to address AI is another question, although, under the Online Safety Bill, the latter eventually plans to).

By contrast, independent press regulator Impress recently updated its Standard Code pertaining to AI-generated content. Soon after technology site CNET allowed AI to write articles, only to inadvertently and repeatedly publish false information, Impress asked publishers to “be aware of the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and other technology to create and circulate false content (for example, deepfakes), and exercise human editorial oversight to reduce the risk of publishing such content”.

[Read more: ‘You do not automate people out of their jobs’: Data journalism bosses on the rise of robots]

The future of journalism

A double-edged sword, AI may see newsrooms cut down on human authors to save costs – even as it disrupts a decades-old revenue model rooted in digital advertising.

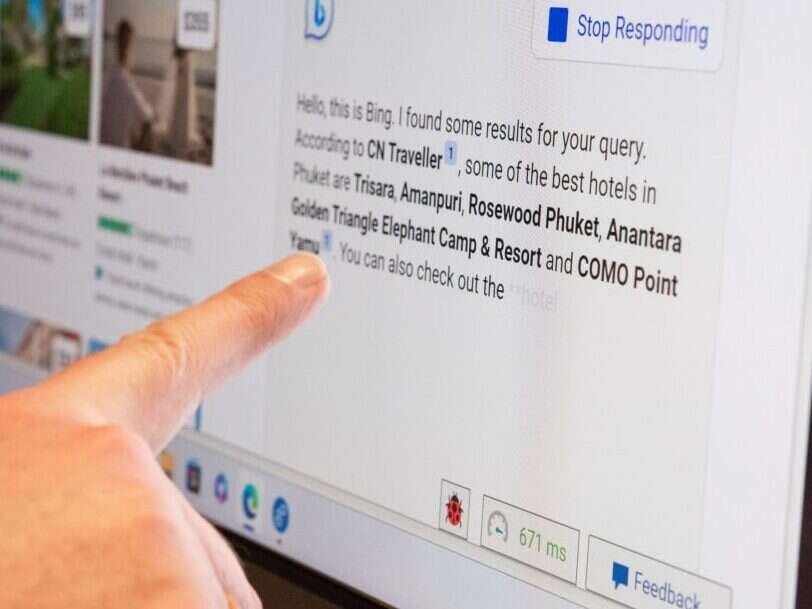

Publishers and search engines rely on users giving their attention to advertisements. Until now, the model has worked by way of users typing questions into a search engine (which derives ad revenue by promoting sponsored links) before being directed to third-party websites for answers (which in turn derive ad revenue via third-party ads). But if ChatGPT has already trawled the internet, read relevant links, and packaged the answer in a concise paragraph, perhaps users no longer need to browse the internet at all?

This will likely result in a paradigm shift in the relationship between publishers, advertisers and search engines as browser behaviours evolve in line with new technologies. New funding models may emerge, and we are yet to see how powerful AI chatbot tools might integrate affiliate links and third-party ads.

However, whether this means that AI will “steal” journalists’ jobs is questionable. Buzzfeed themselves stated that human-generated content would remain at the core of its newsroom, deploying AI for tailored content such as its famous quizzes and listicles.

Capitalising on AI innovation in journalism

The relationship between AI and journalism may be in the spotlight – but it isn’t new and it’s not all bad. Outlets such as Forbes have leveraged AI for years, creating automated and simple reports. In an era of relentless content, where outlets fight for speed and cut-through, AI-informed headlines and summaries can make research and writing more efficient for time-pressured journalists.

But even with the rise of more sophisticated automated content, it seems unlikely that newsrooms will rely on AI alone to create articles. Established and respected media brand names, earned through decades of painstaking research and careful and balanced reporting, will be loath to have their credibility and reporting ingenuity challenged.

In conclusion, it’s fair to assume that AI will test whether existing regulation around IP authorship, content verification and moderation, and newsroom operating and funding norms are fit for the modern age. While there will always be a place for the journalist, so too do we stand on the precipice of a new era in which AI is here to stay.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog