The phone records of a Daily Mirror journalist were being snooped on as part of two separate investigations into leaks being run simultaneously by the same police force.

Mirror North East correspondent Jeremy Armstrong has been told by Cleveland Police that it used the Regulations of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) to monitor calls on both his work mobile and landline over nine days from February 20, 2012.

The fresh revelations come after the Mirror contacted Cleveland Police about its targeting of Armstrong’s mobile phone over four months, from 1 January, as part of a probe to find the source of three stories leaked to the Northern Echo in April the same year.

In that instance, Armstrong’s mobile phone number was put next to the name of an Echo reporter in what police have claimed was a “mistake” on the RIPA application, which they signed off themselves.

The phone records of Echo journalists Julia Breen, Graeme Hetherington, former Cleveland police officers Mark Dias and Steve Matthews, and a lawyer were also targeted by the force on this occasion.

Last month, Dias and Matthews took their case to the Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT), which rules on police abuse of surveillance powers.

Judges made clear they would find the police acted “unlawfully” by grabbing the pair’s phone records, with a final judgement set be released within weeks.

Armstrong told Press Gazette he had no idea that police were spying on him until he was contacted by Dias in November last year, ahead of the hearing.

He said: “It’s shocking that they have gone to those lengths to try and take down sources on a story – I was taken aback by it.”

Cleveland Police has since apologised to Armstrong for its actions. But, while the force’s police chief claims to have personally contacted Echo reporters to apologise about the matter, Armstrong said his only contact with the force was through a letter sent to the Mirror.

Police told the paper: “In 2012 the force made a mistake and wrongly associated a reporter’s phone number with an investigation into police leaks. When the error came to light in November 2016 the number and all associated information was destroyed and the individual informed.

“The number, and another belonging to the same reporter, was – back in 2012 – part of a separate investigation into leaks and this may be how the mistake happened; however this is still being looked at and we can’t say for certain. We are keeping the individual updated.

“We are very sorry for the mistake and the review into it forms part of a big piece of work taking place now to make sure nothing like this happens again”

Armstrong (pictured below with Mo Farah) said he found the notion that the police had erred in putting his number next to the wrong name in the snooping application “rather difficult to believe if I’m honest”.

“There are two possibilities,” he said. “There’s been a cock up, which is their version of events, or there’s been a conspiracy, and conspiracy is rather dark in this particular instance because you have to ask yourself who is going to benefit from this information?

“We have got to ask the question, do the powers really justify that level of intrusion and I don’t think they do. What they are talking about is not even an arrestable offence. It isn’t even a criminal offence. But they are using laws which have been brought in to fight terrorism and corruption and fight crime.”

He added: “Best case scenario is we have got two sets of officers at the same police force unlawfully accessing my data in order to prove something that won’t be a criminal offence were it proven.

“And what they were looking for they got completely wrong. The premise was wrong, the reasons were wrong. It makes me want to see if these powers have been used on others by other forces and if they are aware of it because I wasn’t aware of it for four years.

“I do struggle to see how they could [make the mistake] really, to be honest. Because when you ask for phone records you have got to be so clear about what you are asking the telephone company.

“If you give them a number, it’s going to show up as a belonging to a company at the very least because my bills were paid for by Trinity Mirror. The police are going know reasonably swiftly that it isn’t the Northern Echo paying the phone bills.

“It begs the question, was it done for a different reason? Was it done for subterfuge? Were they doing it to make it seem like they were looking at the Northern Echo when in fact they were looking at something else?”

Armstrong said he had been writing stories on Cleveland Police around the time both probes into his phone records were being carried out simultaneously.

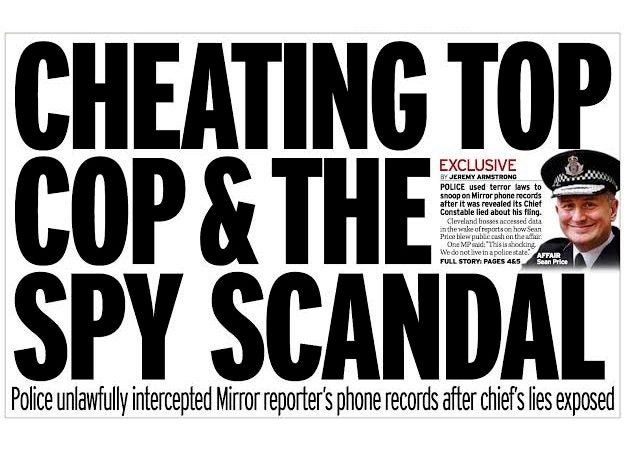

The Mirror exposed its then Chief Constable Sean Price as having an affair with his chief staff officer Heather Eastwood and later wrote about his dismissal for gross misconduct over lying and bullying allegations.

Said Armstrong: “There were a number of stories because he [Price] was at the centre of a scandal and was arrested. There was intense interest in what he was doing while he was in office. That’s what I was writing about at the time [police spied on my phone records]…

“When I look back at the stories we did in that period and also the FoI requests to Cleveland, it becomes then even more difficult to believe that the stories I was doing at the time weren’t the motive for [them spying on me].”

He added that while police had targeted his work phone, it was the only mobile phone he owned.

“I was getting calls above and beyond work just as anyone does on any work phone,” he said. “It’s a bit weird because they are spying on incoming and outgoing calls to my phone. It’s a weird thought to think that they can look at where you have been if they wanted to.”

Armstrong, who has been at the Mirror for 25 years and began his journalism career in 1988, said learning of the police surveillance had made him rethink his approach to his job as a journalist.

“It makes you immediately think ‘do I have to review how I work in future?’,” he said.

“It makes you think about how you set things up for stories, where maybe I wouldn’t have analysed it that much deeply prior to this happening. It makes you think if they could do it in this instance on something so trivial, could they do it for something else?

“We deal with people all the time who maybe need protecting because of what they do and the information they have got and we really have to think about how we look after them.”

Armstrong said that telecoms records surveillance, now covered by the Investigatory Powers Bill, “should be done only in the most extraordinary and extreme circumstances and in this instance – and I think it’s true of not only me but with the Northern Echo reporters – it just didn’t justify that level of intrusion.”

Under the new legislation requests to view telecoms records made in order to identify a journalistic source must be approved by a judicial commissioner (but are made in secret to telecoms providers).

A Trinity Mirror spokesperson said the publisher was “considering our legal options” over whether to pursue the matter at the Investigatory Powers Tribunal. It is understood no decision will be taken before the verdict is delivered on the Dias and Matthews case.

Armstrong said he didn’t believe pursuing the matter would achieve anything more than has been achieved already.

He said: “The police have already admitted what they have done. It’s been aired in court. We have got a story on it. Part of me thinks what would it achieve? I’m not sure we would know a lot more.”

But, he added: “It does shine a light on how arbitrarily these RIPA powers are used. The application went in and before I knew it they had four months of my call data.”

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog