Independent journalism appears to have been a victim of the Ukraine invasion following the passing of the Russia fake news law.

Numerous domestic and foreign publications have suspended reporting in Russia or closed altogether. Meanwhile in Ukraine, five journalists have been killed apparently as a result of deliberate attacks by Russian military forces on the media.

The new law criminalises the dissemination of “false information” about the Russian military.

The least serious punishment the crime levies – for those found guilty of passing “deliberately false information” off as “reliable reports” – is either a fine of between ₽700,000 (£4,800) and ₽1.5m (£10,000), “compulsory labour” for up to three years, or “corrective labour” for up to one.

The same act deemed to have been carried out “by a person using his official position” – presumably including any journalist working with an established outlet – produces a fine between ₽3m (£20,600) and ₽5m (£34,000), imprisonment for up to ten years, or compulsory labour for up to five.

Finally, should someone using their official position to spread falsehoods about the Russian military and its campaigns also be found guilty of causing “grave consequences” – a term undefined in the law itself – the imprisonment period rises to as high as 15 years.

Formally an amendment to Article 207.3 of the Russian Criminal Code, the law passed quickly through the Russian legislature on Friday 4 March 2022. The text of the law in Russian can be found here.

Although it is unclear whether anyone has yet been prosecuted under the law, outlets around the world have pre-emptively tried to protect staff from prosecution.

Press Gazette recaps below the effects the law has had so far on some publishers reporting from Russia. The list is partial – please bring more cases to Press Gazette’s attention by emailing pged@pressgazette.co.uk.

Russia’s fake news law and the information war with Ukraine

Novaya Gazeta

In a brief article published on Monday 28 March, Novaya Gazeta said it would halt publication online and in print until the “special operation” in Ukraine had ended. The outlet said this followed a second warning from Roskomnadzor, the Russian government’s mass media and telecommunications regulator.

The well-known opposition newspaper, which is edited by 2021 Nobel Peace Prize winner Dmitry Muratov, had earlier said on Friday 4 March that it would remove material from its website that covered the invasion of Ukraine.

It subsequently began referring to the war obliquely to avoid falling foul of the law. An article about Russian rock music, for example, replaced references to the word “war” with “[special operation]”, the Russian government’s preferred term for the invasion. A sentence in an interview with a Russian emigrant was transcribed in Russian as: “I was morally knocked out by the very fact [of actions that are forbidden to be named by Roskomnadzor]”.

The New York Times reports that Zelensky gave a 90-minute interview to four prominent Russian journalists on Sunday 27 March. One of the journalists, Mikhail Zygar, reportedly asked a question on behalf of Novaya Gazeta – but, in light of the “fake news law”, the publication was not among those to publish the interview.

Muratov told the NYT: “We have been forced not to publish this interview. This is simply censorship in the time of the ‘special operation.’”

Novaya Gazeta journalist Nadezhda Prusenkova told US state-funded broadcaster Voice of America on 11 March: “When the law on fake news came into effect, almost 30 media outlets were blocked, closed or destroyed. Journalism has been lost in Russia — it just doesn’t exist anymore. Independent journalism, at least.”

Channel 1

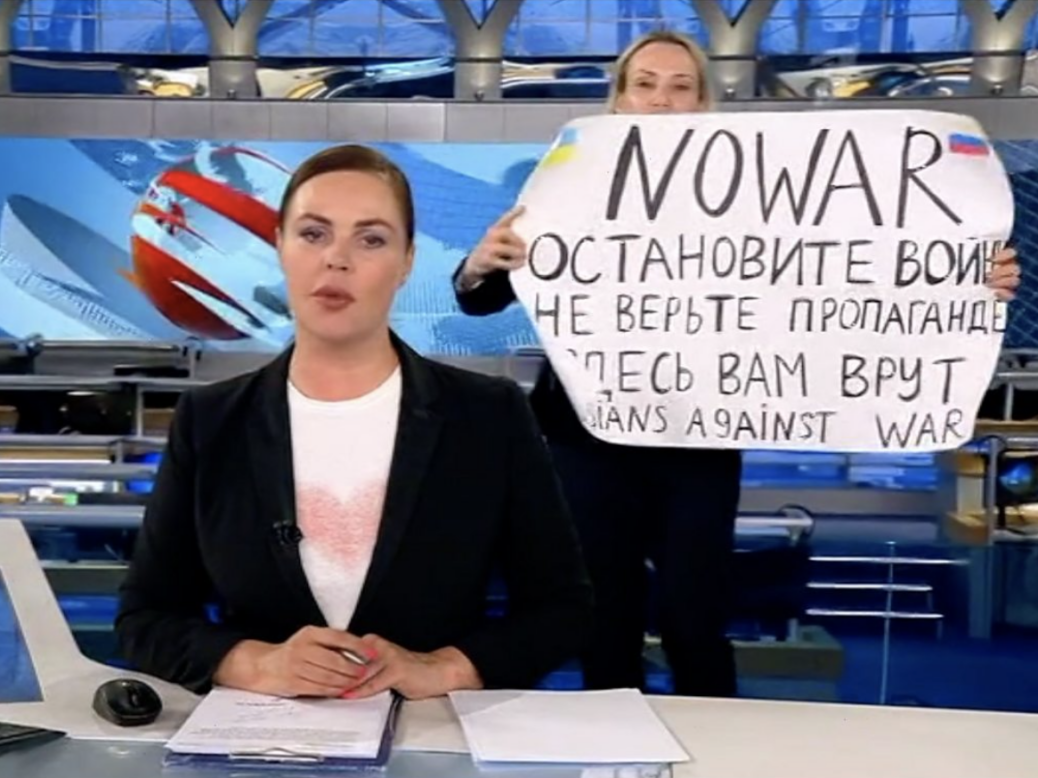

Marina Ovsyannikova, an editor with Russian state broadcaster Channel 1, on Monday 14 March crashed a broadcast of the evening news with a sign reading “No war, stop the war, don’t believe the propaganda, they are lying to you here.”

(In line with its approach to the censorship law, when reporting the incident Novaya Gazeta blanked out the words on the sign.)

В эфире программы «Время» за спиной ведущей Екатерины Андреевой появилась девушка с плакатом, содержание которого нам запрещают передать Роскомнадзор и Уголовный кодекс.

По неподтвержденной информации, это редактор Марина Овсянникова.

В настоящий момент она задержана. pic.twitter.com/TdpkscVpuS

— Новая Газета (@novaya_gazeta) March 14, 2022

Beforehand, Ovsyannikova recorded a video in which she explained in Russian that her father is Ukrainian, said she was ashamed of having worked for the broadcaster, and called for anti-war protests.

Unaccounted for overnight, a picture circulated the next day depicted Ovsyannikova apparently in court alongside lawyer Anton Gashinsky. She told reporters that she had been questioned for 14 hours during this period.

The BBC reported that Ovsyannikova was charged with organising an unauthorised public event, rather than an offence in the “fake news law”. She was fined ₽30,000 (£214) for her video message.

Meduza

Latvia-based Russian and English-language news site Meduza had its website blocked in Russia on 4 March, prior to the fake news law’s passage through the Russian legislature. Much of the publication’s Russia-based staff fled the country following the passage of the law.

Meduza investigative editor Alexey Kovalyov tweeted on 5 March that he had left Russia, “crossing the border on foot in the middle of the night, with my panic-packed bags on my back and my dog in tow”.

The reader-supported outlet has launched a fundraising effort in a bid to continue publishing. The initiative is being supported by western publications including Mother Jones, Krautreporter, the Center for Investigative Reporting, the Center for Public Integrity, Buzzfeed News, Grist and Huffpost.

The Moscow Times

Online newspaper The Moscow Times announced it was suspending its Russian-language reporting because of “a new repressive law, which actually introduces censorship prohibited by the Constitution of the Russian Federation”. English-language coverage continues.

It’s My City

Like Novaya Gazeta, Yekaterinburg news site It’s My City said on Telegram the day the law passed that it would be removing content about the war, saying: “In the current situation, we cannot put journalists at risk.”

[Read more: Ukrainian publishers increasingly using secure app Telegram to reach readers]

The Bell

Another independent news site, The Bell, said on Telegram that following the passage of the law “we have decided to completely stop covering the ‘special military operation'”.

Znak.com

Yekaterinburg-based independent outlet Znak.com suspended operations altogether “due to a large number of restrictions that have recently appeared for the work of the media in Russia”, according to a note on the now otherwise blank site.

TV Rain

Youth-oriented television station TV Rain (also known as Dozhd) was shut on Tuesday 1 March, before the introduction of the “fake news law”. The channel ended its final broadcast by showing old footage of a performance of Swan Lake.

Deadline reported: “The Swan Lake bit was an inspired, highly-evocative gesture, especially for Russians who could recall the coup of August 1991 when, unable to actually report the news, stations simply played footage of the ballet for three days nonstop.”

Ekho Moskvy

The Russian prosecutor-general’s office also ordered independent radio station Ekho Moskvy off air. On 3 March the channel’s board voted to liquidate the outlet, according to Radio Free Europe.

Russia’s fake news law: Impact on foreign media

Numerous English-language outlets have suspended coverage or removed their journalists from Russia as a result of the law. Several, including the BBC, Voice of America, Radio Liberty and Deutsche Welle, already had their websites blocked in the country earlier on the day the law was passed.

-

- The BBC became the first major publisher to suspend its coverage from the ground in Russia on Friday 4 March; it continued to broadcast in Russian to the country, however, and promoted deep web editions of its foreign-language editions to help readers evade detection. Four days after the suspension the corporation announced it was resuming coverage – one of few outlets to do so. The BBC said of the resumption: “We have considered the implications of the new legislation alongside the urgent need to report from inside Russia.” (The BBC clarified after the publication of this article that field coverage from Russia was only resuming in English.)

- Canadian national broadcaster CBC/Radio-Canada followed the BBC on 4 March, announcing it too would freeze reporting from Russia: “In light of this situation and out of concern for the risk to our journalists and staff in Russia, we have temporarily suspended our reporting from the ground in Russia while we get clarity on this legislation.”

- Bloomberg News also suspended coverage from Russia on 4 March. Editor-in-chief John Micklethwait said: “The change to the criminal code, which seems designed to turn any independent reporter into a criminal purely by association, makes it impossible to continue any semblance of normal journalism inside the country.”

- CNN said in a statement on the night of 4 March that it would “stop broadcasting in Russia while we continue to evaluate the situation and our next steps moving forward”.

- CBS News announced their suspension the same night, telling Deadline it was “not currently broadcasting from Russia as we monitor the circumstances for our team on the ground given the new media laws passed today”.

- Deadline also reported on 4 March that ABC News had suspended coverage in Russia. A spokesperson told the outlet it was “not broadcasting from the country tonight. We will continue to assess the situation and determine what this means for the safety of our teams on the ground.”

- The Washington Post did not suspend its coverage from Russia, but on 5 March said it would be removing its journalists’ bylines from some Russia stories as a precaution.

- The New York Times on Tuesday 8 March became the first major outlet to announce it would be removing journalists from Russia altogether.

- Conde Nast chief executive Roger Lynch said on 8 March in a memo to staff that “we have decided to suspend all of our publishing operations with Condé Nast Russia at this time”.

- Open-source investigation outlet Bellingcat was blocked inside Russia on 16 March.

Many of the above outlets continue to report from from Ukraine.

Read more:

How UK news organisations have committed staff to cover war in Ukraine

US news media coverage of the war in Ukraine

How journalists have come under attack by Russian forces in Ukraine

Picture: Channel 1 via BBC News

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog