When Press Gazette meets Hassam Eesa, co-founder of an underground network of citizen journalists reporting from inside the besieged Syrian city of Raqqa, he’s not slept a wink.

The former law-student has been making the most of his short stay in London with what appears to have been a thorough exploration of its nightlife after attending the One World Media Awards the night before.

His group, Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently, was given the Special Award for their work exposing the atrocities being carried out by Islamic State (also called Isis) and the Bashar Al-Assad regime in the city through their news website and social media profiles.

I almost don’t notice him when he walks into the lobby of the central London hotel where we arrange to meet. He looks so much like a Londoner in skinny blue jeans and a black sports jacket.

Sat in Hassam’s hotel room, it feels rather like Citizen Four, the Edward Snowden documentary that involved interviews in similar surrounds with the world’s most famous whistle blower.

While Hassam and his colleagues don’t have the US government on their tail, their lives, particularly those of the 18 citizen journalists working for RBSS on the ground in Raqqa, are fraught with peril.

The group has been declared an enemy of God by Islamic State and two of its members, Ibahim Abd al-Qader and Al-Moutaz Bellah Ibrahim, have been killed by the terrorist group within the last two years. They are among 27 journalists and media workers killed by Islamic State since 2013, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. Another 11 are missing and feared dead.

Hassam says of the group’s beginnings: “We were all of us working against the Syrian regime. Then when Isis came and controlled Raqqa they began to make a new law in the city, like Sharia law, and we decided to do something for our city, our country.”

That something was starting an account on Facebook and Twitter called the Raqqa Blog which, in April 2014, turned into news website Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently.

“We decided to make Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently because no-one around the world could see what was happening in Raqqa and at this time Isis were arresting people, killing them,” says Hassam. “There were executionsin the street. And no-one could take a picture or video to publish it to the world to see.

“We decided on the name because at this time Raqqa was being silenced. No-one was hearing about Raqqa and no-one can imagine what happened in this city. So we chose that name and we published Isis crimes, executions and flogging and everything in the city. Also, we covered the people, the civilians, how they can live and buy something or pay the tax for Isis.”

He says that when Isis began to emerge in 2013, he and his friends thought they would be like any other terrorist group in Syria. Another Al-Qaeda or Al-Nusra and the like who would probably disappear in a few months. “But with time we saw things were different,” says Hassam.

“Isis started a lot of things like floggings – putting people in the street for three days – and executions – putting people’s heads in the street – and taking the children to the camps and pushing the people to marry their daughters to fighters. Everything changed.”

A report by the Syrian Centre for Policy Research puts the death toll from the conflict in Syria at 470,000. An estimated 11.5 per cent of the country’s population have been killed or injured since the crisis erupted in March 2011 and nearly half of the population, which pre-war was more than 22m people, has been displaced, which in turn has fueled the ongoing migrant crisis in Europe.

Hassam tells me he had to flee Raqqa, the city where he was born and raised, following his attempts to document Islamic State’s early acts of brutality with a smartphone camera. He now makes up one of ten RBSS staff working outside of Syria.

“I filmed a guy who was being flogged by Isis because he sat with a girl in a garden,” he says. “From this moment I was a wanted man so Isis tried a lot to arrest me because I filmed this for two minutes with my phone and I made a report with the guy.”

Hassam was forced to flee Syria after receiving a message from a friend in Raqqa who told him: “Isis now know you and have more information about you. You have to go. You have to leave.”

He adds: “Our work is undercover and we’ve got risks but we decided to be against Isis because we knew if we didn’t do something, no-one would do it for us.”

Like most of his friends – now also his journalism colleagues – Hassam had been a university student. He studied law in Damascus, Syria’s capital city. None of the members of RBSS had been journalists of any description, he says. So why did they decide to fight Isis in this way?

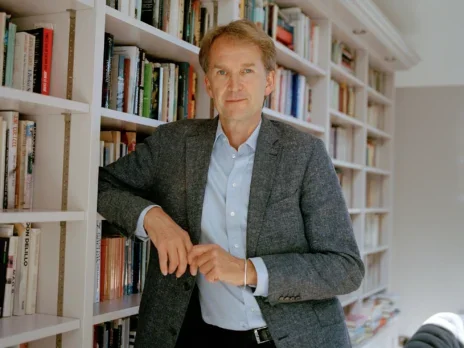

Hassam Eesa, co-founder of Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently, collects the Special Award at the One Wold Media Awards

“We believe that this way is the best way to fight these groups. Not just Isis, because in Syria we have ten or maybe 20 groups like Isis but Isis is the most famous one and the most powerful. All of us are students who believe that we can fight them with pens, with cameras and fight them in the same way they use it to push people to join them.

“We have family and none of us wants to see his sister or brother with Isis. And also we don’t want anyone in Europe, or the whole world, to become an Isis fighter, so we had to do something and we decided to fight them in this way because we don’t believe in weapons.”

Hassam tells me that living under Isis is “like going back 2,000 years”. “There’s no water, no electricity, no anything. You have to pay a tax to Isis, and you have to just be silent. You cannot talk, you cannot think. The girls have to cover everything. The men have to grow a beard.”

Isis has put modern technology at their heart of its campaign of terror with social media in particular playing a big part in propaganda and recruitment. “We use it the same way to fight them,” Hassam says.

He reveals that while Twitter and Facebook are useful tools for sharing stories, they can be hacked by Isis “who have a lot of people who are smart” so are not suitable for private message sharing. RBSS has gotten around this problem by engineering their own secret messaging service.

“We use our own programme – like a Whatsapp or Viber,” Hassam explains. “Our friends helped us to make it. The guys from Raqqa send us a message and sometimes videos or pictures and then delete it automatically from their device.

“They would face arrest if they were caught. Because of that we don’t use Facebook or Twitter to send messages between us. Once it’s outside we publish it online.”

The group’s website is under daily attack from Isis hackers, he reveals. An NGO, who Hassam says must remain anonymous, helps the group to keep it up and running and aids in the translation of news stories from Arabic into English.

He said the group’s reports have helped, at least in part, to reclaim Raqqa’s online reputation from the rampant ideology of its extremist captors. “If you googled Raqqa in 2014 you just saw Isis material, Isis ideology, photos from Isis, videos from Isis,” he says. “Now if you google Raqqa you will see a lot of journalists, a lot of media, talking about Isis. I think in the first few results you will see our material.”

As for how the western media has been handling the conflict in its reports, Hassam is modest and claims he’s not a “professional” and so cannot pass judgement, except to say that in general the media are “doing a good job”. But he does express frustration at the west’s obsession in reporting on acts carried out by Isis over other terror groups and the actions of President Assad’s regime.

“The media here and in Europe needs to focus on the other groups in Syria, not only Isis,” he says. “Assad has used rockets and also chemical weapons against civilians and no-one talks about that, but if Isis kills a man in the street you will see a lot of media talk about it.

“No-one in Syria wants any civilians to die but when we see for example the last terrorist act in Orlando and the US there were about 50 civilians killed and all the newspapers were talking about the guy who was shooting inside the club. Every day in Syria, 100 civilians are killed but no-one talks about that.

“The most important thing in my opinion is covering all of Syria, all of the terrorist groups, not focusing just on Isis.”

In a chilling reminder of how the conflict is far from ending, Hassam tells me: “At this moment there are 1,000 children in Isis camps. Just imagine these people after two or three years of Isis training and ideology, when they grow up then we will have a big problem and another group that I think will do more crimes and more bombings and more terrorist acts in the world.”

So how can they be stopped? “We are fighting in our magazine,” says Hassam.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog