The local news problem is simply stated: fewer people want newspapers because their phones are better at providing them with information on demand. And the economics of providing local news digitally are all but impossible: local audiences are too small to generate the page views needed to fund them via advertising.

As a rule of thumb, an individual reporter needs to drive millions of page views per month to generate enough ad revenue to cover newsroom costs. And even if a local publication could get that level of traffic, local advertisers don’t have big enough budgets to sustain them.

The result: hundreds of local newspapers have closed in the UK since 2009 and in the US, two local newspapers close every week, on average.

Yet a small number of digital-only local newsrooms are starting to thrive and grow.

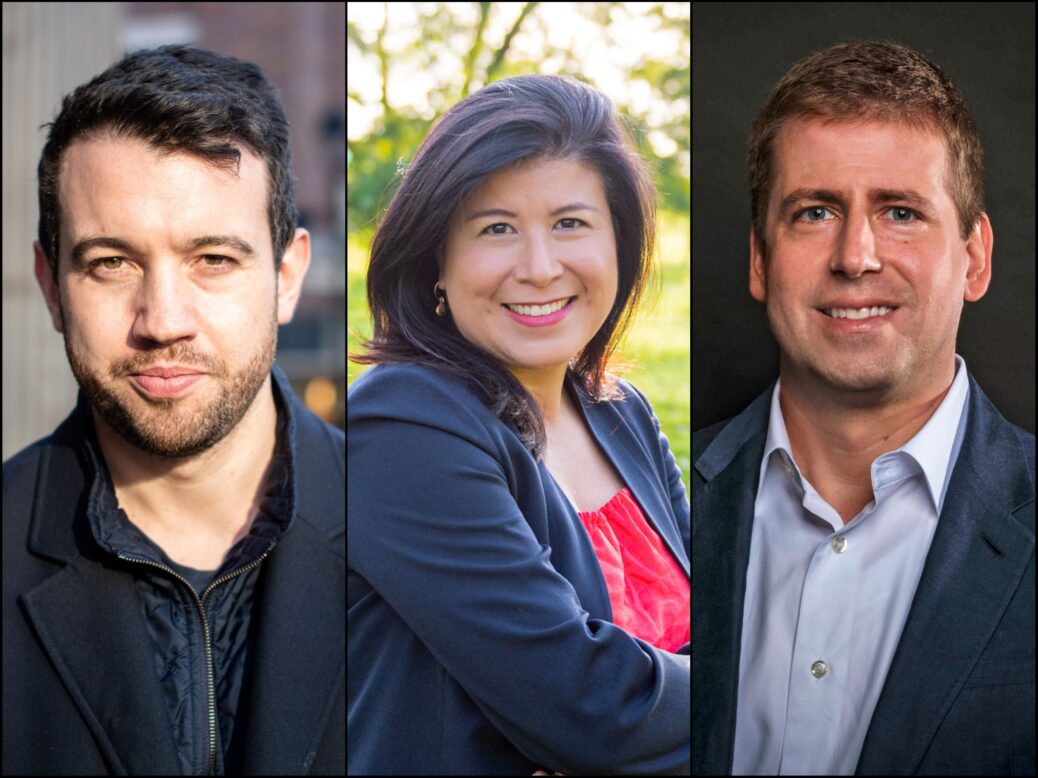

We talked to three bosses at flourishing local digital newsrooms — Axios editor-in-chief Sara Kehaulani Goo, who runs 30 Axios Local news brands in the US; Joshi Herrmann, editor of The Mill (Manchester), The Post (Liverpool) and The Tribune (Sheffield); and Scott Brodbeck, founder of Local News Now (LNN), which runs three sites in Arlington, Fairfax and Alexandria, all in the US state of Virginia — to ask them how they succeeded where everyone else seems to be failing.

In our conversations, a set of themes emerged: the financially stable future of digital local news will probably be small, highly focused, and based on email, they told us. And although the finances are sustainable, the margins are thin.

‘Reader habits die much harder’

LNN’s Brodbeck summed it up: “It’s a notoriously shitty business. I probably would be a lot wealthier if I just owned a series of Airbnbs or something.”

That said, LNN’s three sites — ARLnow, FFXnow, and ALXnow — get about one million page views a month and generated about $1.25 million in revenues last year. He’s pacing 10% ahead of that this year.

Brodbeck estimates 75% of his revenue comes from direct sales to clients and 20% comes from programmatic. Some 36,000 readers subscribe to his emails, and he has just ten employees.

Crucially, his top source of traffic is neither Google nor Facebook, both of which have dialled down the presence of news in their rankings. Rather, it’s direct: people pulling up the homepage from their bookmarks or tapping into it from an email newsletter.

“What Vice and Buzzfeed were doing was relying on social algorithms to get people to their sites and that worked for a time,” Brodbeck says. “But obviously, when you do that, you’re at the mercy of those companies and their algorithms, and there’s no guarantee that that’s going to last. Reader habits die much harder.”

Axios Local is much bigger: it has 30 local email newsletters with 1.6 million subscribers, served by 100 staffers. The top six cities have more than 100,000 readers on each list. All of Axios Local’s revenue comes from ads in those emails. Axios Local booked $8.6m in revenue last year and $7.5m through May of this year, the company confirmed.

“What we are seeing is progress in terms of building an audience and building revenue. And we definitely are confident now that we’re two and a half years into it that it will work if you just play out the numbers and the scale over time,” says Goo.

Both Axios and LNN run incredibly lean operations: typically, they employ no more than two reporters per city. Those writers focus closely on what readers want and what they can actually deliver. This has had some counterintuitive results.

Traditionally, local papers in America heavily cover high school sports because parents love seeing their kids’ names in the paper. But Brodbeck has banned youth sports coverage from his sites because he was irked by the number of reader complaints it generated.

“We used to get all these emails [which said]… ‘why aren’t you covering my kid’s team?’ And with all that aggravation didn’t come a ton of readers to the stories we were publishing. So, I figured out pretty early on that that it was pointless to try to cover high school sports,” he says.

Page views metric has ‘disappeared from my life’

Likewise, the mantra at Herrmann’s The Mill is to reduce quantity and focus on quality.

“My hunch was people probably would get on board with local journalism again, and reading it and trusting it and paying for it, if they were given extremely high-quality stuff but in very low volume,” he says.

The Mill doesn’t even send its newsletter every day. On the days it does, there is often only one story in it — and that story might be 3,000 words long. For instance, The Post recently published an investigation into why Liverpool began building a bridge in a park which no one seems to want and discovered that one city councillor seems to have a conflict of interest in its construction.

“We’ve just reached 5,000 paying subscribers overall at three cities,” Herrmann says. He’s on course for £400,000 in annual revenues, with eight people on the payroll. The Mill has 35,000 subscribers, The Post 16,000 and The Tribune 17,000. He’s looking to open titles in Birmingham and Leeds next.

The audience and revenue numbers at these companies would look like rounding errors at somewhere like News Corp or Gannett. But there is evidence that the future of local news will indeed be small, focused, and based on email. Earlier this year, Reach relaunched nine of its local brands as newsletter-first properties.

And there’s another revolution on the horizon: None of these brands care about amassing traffic to their websites. Instead, it’s the number of paying and registered users who sign up for an email, because that is what drives their revenue.

“I never look at traffic,” Herrmann says. “I don’t look at page views so that metric has just completely disappeared from my life. We all look at one number, which is paid subscribers. How many new paid subscribers do we have?”

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog