State interference, harassment and obstructive US tech platforms are some of the challenges facing BBC World Service journalists.

Some 310 BBC World Service journalists, approximately 15% of the total, are currently in exile due to restrictions on press freedom and bullying by authorities.

Earlier this month the BBC hosted BBC World Service Presents, a three-day event in the lead up to World Press Freedom Day to highlight the challenges experienced by its journalists.

The BBC World Service provides independent news to 318 million people weekly, across 42 languages.

It aims to deliver unbiased, objective news to audiences around the world, particularly in countries where media is state-owned and controlled. In many cases, there is a focus on counteracting misinformation.

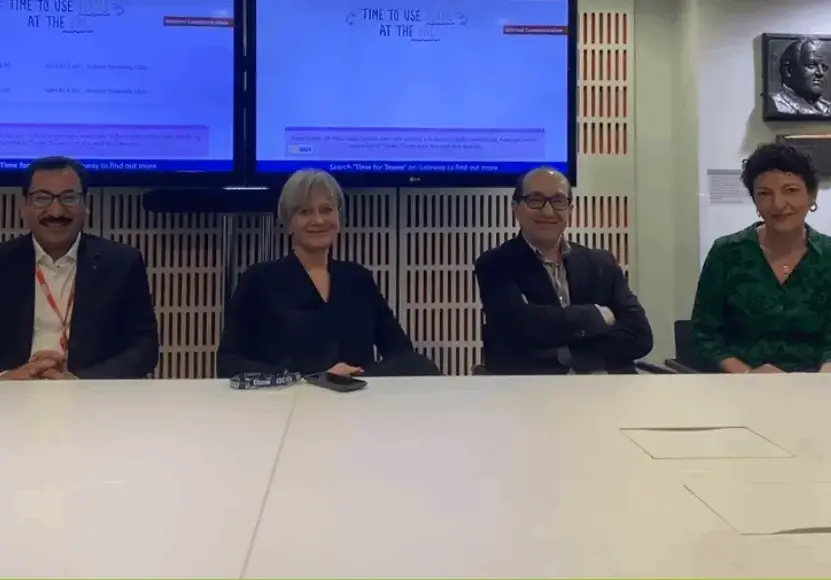

Press Gazette spoke to BBC Russian’s Jenny Norton and Famil Ismailov, BBC Persian’s Rozita Lotfi, and BBC Arabic’s Ashraf Madbouli.

They discussed the role of training, international advocacy and technology in overcoming the challenges they face bringing unbiased news to the world.

BBC Russian: A game of cat and mouse with the censors

BBC Russian has worked in exile since the beginning of the war in Ukraine when it relocated to Riga, Latvia, after its website was blocked by Russian servers.

BBC Russian now relies on Telegram and YouTube to reach its weekly audience of five million.

Facebook is deemed an “extremist organisation” in Russia so is increasingly difficult to access.

News via social media is in most cases, only possible through virtual private networks (VPNs) which establish a connection between your computer and a remote server. Personal information is then encrypted, and users can get around website blocks and firewalls.

The BBC World Service now actively advises people in certain authoritarian states on how to access BBC websites via VPN and the dark web.

Head of BBC Russian Jenny Norton described the process of VPNs being blocked by the state and then reinvented to avoid the blocks as a “cat and mouse chase”.

BBC Russian news editor Famil Ismailov explained why Telegram has been the primary communication platform to Russia: “Number one, it’s difficult to block because of its design.

“Number two, Russian government organisations and pro-Russian government bloggers benefit massively from the existence and reach of Telegram.”

Norton added: “There hasn’t been a Russian domestic chat app that’s had the same reach and influence, and for that reason, everybody’s on it, so it would cause a lot of inconvenience and upset to all sorts of people if Russia were to shut it down.”

All social media algorithms have a say in whether journalistic material is picked up.

Ismailov said: “Social media companies need to be held responsible for what information they prioritise and promote.

“We’ve seen Facebook downgrade news content, we know that Google and other search engines control what they serve first.”

Despite relocating to Latvia, exile has not meant an end to harassment. Last month, BBC Russian correspondent Ilya Barabanov was branded a “foreign agent” by Russia, which he must declare on all publications.

Norton added: “Our own staff were involved in a strange incident in Riga at the beginning of the year when someone threw a firecracker into a bar where they were gathered.

“It may have not been connected to the fact that they were in there, but it certainly contributed to a sense of nervousness and feeling of vulnerability.”

When asked about the role of international pressure, Ismailov said: “President Biden, Lord Cameron, leaders of democratic countries, they should be reminding the leaders of authoritarian states that journalism is not a crime.”

BBC Persian: Journalists banned from going home

BBC Persian broadcasts Persian language service to Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikstan and its journalists have always worked abroad. They were banned from visiting Iran for family events or holidays in 2009.

With 60% of Iranians under the age of 30, often tech-savvy, and bilingual, access to non-Iranian media remains high.

But the use of VPNs could be criminalised in Iran, potentially limiting the reach of BBC Persian.

International advocacy is vital to protect journalists, argued Lotfi, highlighting how BBC Persian had requested that the UN condemn abuse of national security and counter-terrorism laws against its journalists.

Lotfi added: “In 2009 our TV channel launched, and the authorities started to jam the signals, which they temporarily stopped due to international pressure.”

Lotfi explained the escalating persecution of BBC Persian journalists, with 152 staff members or contributors having their assets frozen in Iran in 2017.

Lofti said: “In 2022 after the start of the protests, the Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs put BBC Persian on a list of sanctioned organisations.

“Quite recently, we found out through leaked data by a hacktivist group, that back in 2022, a court in Iran had convicted a number of BBC journalists in absentia and without their knowledge.

“They had been sentenced to one year in jail under charges of propaganda against the Islamic Republic.”

Of the BBC News Persian staff, 60% of survey respondents reported being harassed, threatened, or questioned by Iran.

She continued to explain the attack specifically on female journalists, some of whom have withdrawn from the profession due to deteriorating mental health.

In a mini-documentary screening at the BBC Radio Theatre, Lofti’s colleague, Farnaz Ghazizadeh described how an image of her face edited onto a pornographic photo was sent to her teenage son.

Gendered harassment is far from Persian specific, with a recent survey revealing that a fifth of women have considered leaving the UK media as a result of feeling threatened or unsafe in their profession.

BBC Arabic: Journalists face bullying and harassment

Members of the BBC Arabic team still work on the ground in the countries they cover, but at some risk – according to Cairo bureau editor Ashraf Madbouli.

Madbouli said: “We need to make sure that journalists are getting the support they need, when they need it, because the bullying will continue.”

He added: “We need to train journalists in how to deal with bullying, to keep them stay solid and steadfast against any kind of harassment towards them or their families.

“But when I say training, I do not mean an organised lesson, I mean a notion in the mind of big media outlets.”

When asked about provisions and support for journalists, Madbouli said: “The duty of care we talk about should also extend to citizen contributors, those who fill the shoes of reporters when journalists are sent into exile.”

He added: “Israel says that Gaza is not safe for journalists to enter independently.

“But I would say that the safety of the aid workers, who are allowed in, is like the safety of the journalists, who are not.”

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog