Anyone with a news app installed on their phone would likely have noticed that news publishers are not shying away from push alerts.

Press Gazette’s own analysis of mobile app push alerts sent between 16 September and 1 October (which included the Queen’s funeral on 19 September), found that the 27 international, national and local publishers at which we looked together sent over 2,300 alerts.

Data from mobile app specialists, Airship supports these trends. In 2021, the worldwide publishers on its platform – among them the BBC, Sky News, Reach and CNN collectively sent 446bn push alerts- a 2% increase compared to 2019 and 28% more than in 2018. (2020’s exceptionally big spike in alerts was an anomaly due to Covid-19 explains Patrick Mareuil, Airship’s managing director for EMEA). More recently, the Queen’s death resulted in an additional 2bn notifications sent by the media companies in Airship’s platform between 7 and 19 September, compared to the the same period in August.

While push alerts form part of many publishers’ digital strategies, approaches vary. The Washington Post sent the most alerts in the 17-day period we looked at (147), followed by The Telegraph (140) and Reach-owned MyLondon (125 alerts). Where the option to personalise alerts was available, we opted in to receive general and breaking news alerts but excluded opt-in push alerts on specific themes such as climate, US politics, or Covid-19 meaning that our totals will be conservative. The average publisher in our sample sent four alerts a day, although this varied depending on the day’s news agenda. Perhaps unsurprisingly more alerts were sent on weekdays.

According to a 2020 study by AP, for most publishers push notifications only drive a single-digit percentage of total traffic. Advertising revenue, building a habit with a brand and demonstrating editorial priorities and voice to audiences are however, among the reasons publishers use push alerts. Evolving technology around mobile web push notifications and temporary notifications linked to live activities such as sports events are also areas increasingly of interest to publishers.

"When you send push notifications to users on a weekly basis, you have a retention rate after 90 days that is six times higher than if you don't send those push notifications," says Mareuil. According to Mareuil app users that opt-in to push notifications generate five times more advertising revenues than those who do not.

Open rates on push notifications for news (3.5% on Android and 3.2% on iOS), while slightly lower than cross-industry figures have increased in recent years.

Open rates however, don't tell the whole story for news. Many push alerts provide casual readers with enough information in the lockscreen.

While push alerts have historically been used for breaking news, publishers are increasingly using them to drive engagement with other types of content.

"Media publishers more and more are now trying to send slower content and more personalised content, meaning that they really want to understand what are the types of articles and topics that users want to receive", says Mareuil.

In our sample, less than 20% of the alerts used the term "breaking news" in the lock screen summary, although some publishers share breaking news without explicitly using the term in the alert. Publishers such as Metro, Washington Post and the New York Times meanwhile regularly used alerts to push edition products such as the Washington Post's 'The 7' newsletter which rounds up the day's top seven stories or New York Times' evening briefing.

Press Gazette spoke to three publishers - the BBC, Reach and the Guardian - to understand how they use push alerts

BBC News: breaking news is the priority but alerts are increasingly used in other ways

"The biggest breaking news is the real priority for push alerts and that's something that hasn't changed. But in the last year push alerts are being used for more varied stories," says Samanthi Dissanayake, senior news editor at the BBC.

Those other stories have included alerts that help audiences make sense of big and long-running stories such as the war in Ukraine or the death of the Queen - alerts are used to highlight key moments and stories within the bigger story. The BBC is also pushing alerts on big investigations, features and more unusual news to try to "broaden the news agenda".

Within this strategy, deciding which stories warrant a push alert is a decision that’s usually made between the newsdesk and curation team, although alerts on big breaking news stories often require a quick response from the newsdesk.

While distilling the biggest stories involves some subjectivity, "picking the best stories and most important stories is not just a game of instincts", says Dissanayake. The selection of stories is driven by balancing what's the most important news as well as audience priorities.

The BBC’s team looks carefully at data insights in a weekly meeting to review past pushes, their performance and their wording. Data helped inform the BBC’s decision to push related human interest angles and stories about other royals in the days after the Queen’s death.

The BBC is known for the speed of its breaking alerts - helped says Dissanayake by having a digital news desk in the centre of the newsroom that is able to source, verify and sub-edit news quickly and efficiently.

"The decision then is what's the key information we need to get out to audiences? What's the most useful form of words for people to understand what's happening?" she says.

But breaking news is not only about being first.

"It's important we are swift, particularly on breaking stories but what matters most to us is getting exactly the right set of information out for readers," she says. "Sometimes it's wiser to go for the wording and the alert that is most likely to be meaningful to readers. So we're always treading that balance."

What makes a good alert for the BBC?

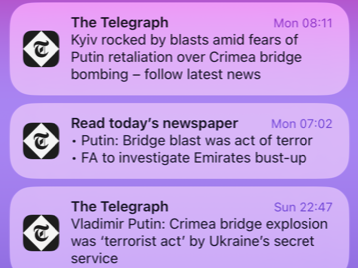

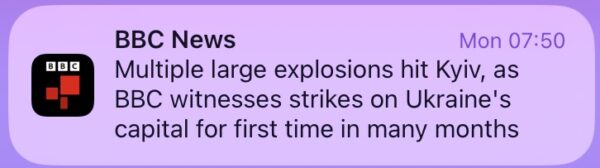

Dissanayake points to a recent alert informing readers that Russian missiles had hit the Russian capital, Kyiv.

"It hits all my key priorities for what we want to push alerts to do. We were pretty swift on it and got onto the breaking news quickly. We explained why it was important …The other thing we did is situate our own reporting in it - we know this because our reporter was on air as the strike started," says Dissanayake.

While the BBC is not chasing advertising revenue, open rates are important for the publicly-supported news provider.

"It’s important that people read the stories, particularly when it comes to the journalism we want to put out there, such as our big investigations," says Dissanayake. "When we’ve uncovered something particularly important it is important to us that we frame the push alert in a way that will make people want to read more. But we also understand that there are some which are about putting down a marker and letting people understand that we are across a story and that they can trust us to mark out the important moments."

Front loading important information and keywords and keeping alerts shorter while providing the right context are some of the ways that the BBC tries to increase open rates.

The BBC does not have specific guidelines to how many alerts it pushes each day.

"Obviously with it being news you have to let the news dictate what the frequency might be," says Dissanayake. "I think audiences are sophisticated enough to understand when there is a huge national or global moment that you will get more alerts."

She adds: "We haven't seen much measurable signs of fatigue when people send more because audiences are pretty aware of how news organisations might use alerts."

Reach Regionals: "Less is more"

At Reach, less is more, says David Bartlett, audience and content director for the publisher’s 40 regional apps.

His main piece of work since he started overseeing the publisher's apps has been to find the right cadence for push alerts.

"If you'd have asked me a year and a half ago how many pushes were being sent across the network everyday it would have been a lot higher than it is now," he says.

"At a certain level the more you push, the more users you lose because people get fed up with being interrupted. Although it's not hard and fast we have a general rule that we'd like our brands not to push more than six times a day.

"Once you go over that the data shows that we lose readers because they tend to not just disable push but delete the app as well."

In terms of what content is selected for a push alert, Press Gazette's analysis showed that a large proportion of alerts from the ten local or sub-UK Reach brands we studied focused on local crime.

"As a rule of thumb we choose the things that are going to perform well from push. We know that by the open rate. It really is big crime, big breaking news, a road closed for a big crash or something like that. Something that's actually useful to you where you live or big national news," says Bartlett.

"It tends to be surprising and shocking news that people open the most. The kind of news that you feel like you need to know rather than 'oh, that's that's interesting'", he adds.

At Reach, the day-to-day decision on which stories should be pushed to phones is made by news editors who, like the BBC, use data to help inform their decisions.

"Once you've had the app for a little bit of time, you can look at the data and interrogate it," says Bartlett.

Yet while news editors use data to help inform decisions on which stories to push, story selection is very much a human effort with news editors’ knowledge of their patch informing the selection of stories which will resonate well locally.

For advertising-funded Reach, push alerts are monetised through advertising impressions when a user clicks on a story. While Bartlett says that app page views are worth less financially than on mobile or desktop, reader loyalty makes them valuable.

"Our loyal readers in the apps consume a lot more pages than the average reader. So even though they don't monetise at quite the same rate they're valuable readers to us because they're consuming that many more pages."

Although push alerts are one piece of the publisher's digital strategy, Bartlett says that Reach is not reliant on pushes. Traffic from alerts while "significant" is not "huge."

Last year in an experiment Reach pulled back the number of push alerts sent by the North Wales Live app from around seven to two a day (before increasing to five or six again once the experiment was over).

"Traffic obviously went down, but not to a huge extent," he says. "The interesting thing was the open rates went up because teams were more selective about the things they sent."

“That's why we can be fairly confident that pushes are best-used just for things that people need to know about immediately," he says.

While Reach has the ability to segment audiences and use rich media in alerts, the publisher has not adopted either of these approaches.

"We've got at least 40 brands on our apps so it's a lot of resources that would have to go into it. Our view is that we aim to provide as good a service as possible, without taking up too much time in any particular newsroom."

The Guardian: "The core is still – and is always likely to be – breaking news"

Since adopting push notifications alongside its first mobile app in 2009, readers have been able to opt in to get Guardian alerts for live blog, a favourite writer and since last year sports. "But the core is still – and is always likely to be – breaking news," says Claire Phipps, digital editor, Guardian News & Media.

The publisher’s strategy for breaking news, says Phipps, centres around "what we think the reader needs to know now". For the Guardian this might include news on significant events that have just happened or are about to happen or exclusive Guardian content such as investigations.

"We don’t have a target of how many alerts we send daily or weekly. It’s wholly guided by the news agenda, although we’re mindful on very busy days that readers want to be kept up to date but might not want to be bombarded," she says.

While speed is important to the publisher, it’s more important, says Phipps, to be right.

"We don't alert to stories that we're not confident about: that might mean we take time to verify a potential terror attack, for example, before sending an alert. You're pushing that information in front of a huge number of people; it needs to earn its place," she says.

As a consequence, the Guardian probably sends fewer alerts than other media outlets with a team of digital editors' in London deciding on the stories.

"We don't want to overload readers, and we don't want to stretch the definition of "breaking news" beyond its limits," says Phipps.

"Working in a digital newsroom, you get a pretty instinctive sense of what does or doesn't reach the bar for an alert; for borderline cases, there's always a speedy discussion. But we don't alert based on what other news outlets have done."

In areas such as sport or during the 2019 general elections where the publisher feels there is substantial interest , the Guardian has set up separate alert categories.

"That all sits very comfortably with our digital strategy which centres on building a lasting relationship with readers, and one in which they trust us and feel we are responsive to them," says Phipps.

For the Guardian, push notifications are not typically seen as a revenue driver, although they can help drive loyalty, says Phipps.

"A high clickthrough isn’t the only measure of a successful alert. For a straightforward news event, a reader might get all they need from the one line of information on their phone screen and that's fine: the journalism is serving its purpose," she says.

Like many quality publishers the Guardian does not use clickbait style alerts.

"I really dislike clickbait-style alerts and would never send one. If a cabinet minister has resigned, tell me who it is: alerts are part of the news, not a hint at it."

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog