The last time I interviewed Ian Hislop, on a warm September afternoon in 2015, the Soho streets around Private Eye’s offices were bustling with tourists and locals enjoying the last days of summer in London.

Hislop – sitting behind his chaotic, paper-strewn desk in the Eye’s higgledy-piggledy townhouse home – was full of energy, enthusing about his journalists’ achievements and the fortnightly magazine’s enduring appeal.

Today, despite the challenges of Covid-19 (not least the mass closure of Britain’s newsagents), the Eye is still going strong – with more subscribers now than at any point in its 60-year history.

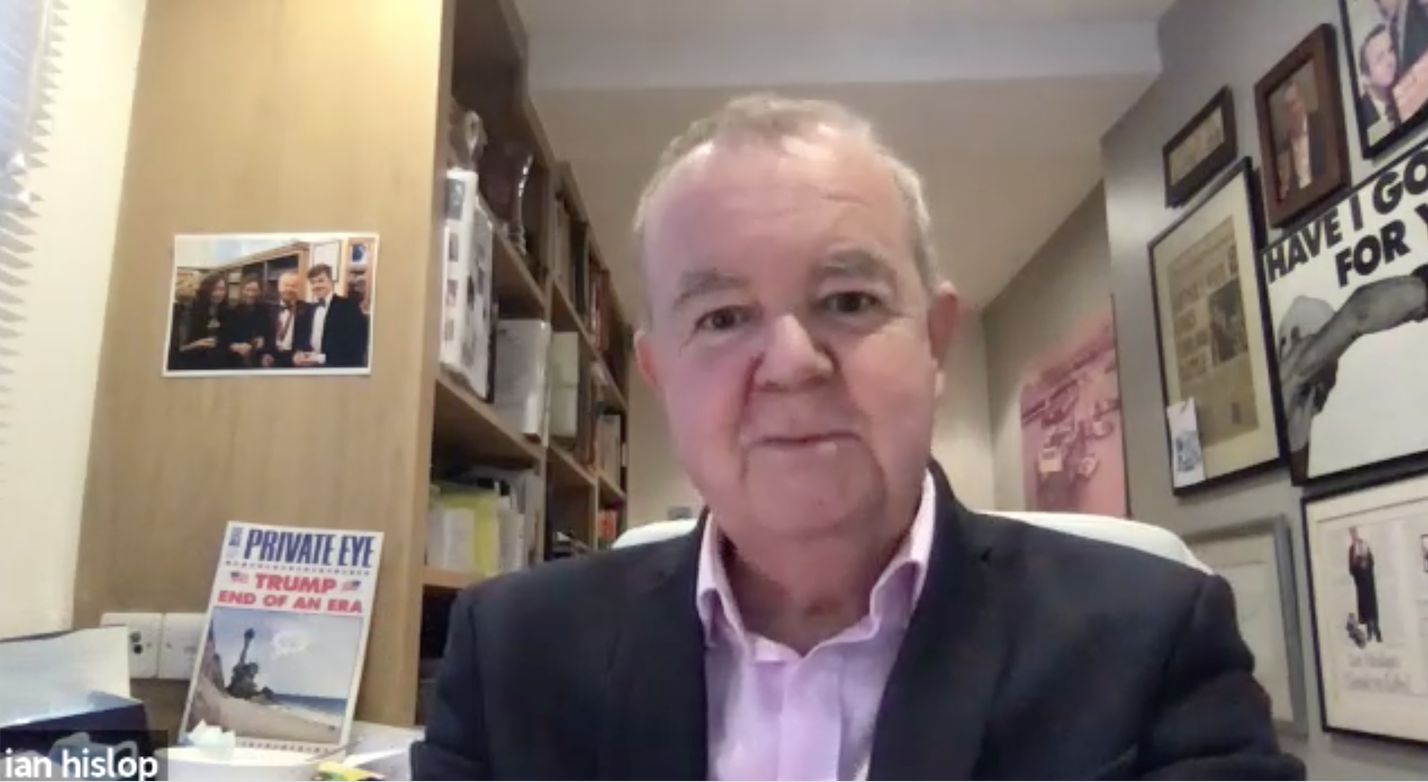

But, Hislop admits over a Zoom interview, it’s not been much fun editing the magazine from his home office (despite his use of Private Eye and Have I Got News For You memorabilia to imitate the appearance of his Soho lair).

“It’s just boring, really,” he says when asked about the challenges of managing a team through video-conferencing software. “I miss their company, for real.

“We weren’t based in Soho by accident. It’s a great place… It isn’t actually. It’s an incredibly boring place at the moment. It’s like a ghost town. Nothing open. You can barely get a coffee there.

“But I very much miss the whole working environment. And being in a studio with people. And having a drink with people – let’s be honest. And all those things that journalists do.”

Digital? ‘We thought about it. But then we often do’

Founded in 1961, Private Eye has established itself as one of Britain’s best known and loved magazines over the past 60 years. The title is renowned for its political satire and gossip, but it is also serious about investigative journalism.

Hislop – who is today well known across the UK for his starring role as a team captain on BBC One’s comedy quiz show Have I Got News For You – moved into the editor’s chair in 1986.

He was 26 at the time, and his appointment – to replace long-serving editor and co-founder Richard Ingrams – caused a stir among the Eye’s older, more experienced journalists.

These days, Private Eye – like other traditional media brands – is more than just a magazine. It runs the prestigious Paul Foot Award for investigative journalism, it has an online video portal called EyePlayer (geddit?), and it has a podcast.

Unlike most other news organisations, though, the Eye does not appear to be overly enamoured with the internet. It doesn’t have a digital edition, and its website appears to be mainly used as a vehicle for promoting the magazine.

Surely Covid-19, lockdown and social distancing rules made you think about doing more online? “We thought about it,” says Hislop. “But then we often do. And then we thought: This isn’t what we do.”

The Eye’s digital avoidance strategy is at odds with the conventional wisdom of the publishing industry. But it appears to be working.

The magazine’s circulation – currently around 236,000, according to managing director Sheila Molnar – is near to the all-time high of 250,000 it set in the second half of 2016.

Its last official ABC circulation figure, for the first half of 2020, was 231,073 – 50,000 more than it was selling 20 years ago. Some 72,000 copies were sold in newsagents – so lockdown presented a serious circulation challenge.

“It was a fairly major shock,” says Hislop, explaining that “nearly everybody who sold our magazine was going to be closed: no Smiths, no travel outlets, no train stations, no airports, no Smiths Travel, no independent book shops. It was a bit terrifying, really.”

How did Private Eye survive?

Hislop points to his 20 March edition, published during the week the UK went into lockdown. It ran with the headline: 48 sheets of toilet paper free with this issue. “That shows you how desperate I was,” he jokes.

Private Eye front cover in March 2020. Credit: REUTERS/John Sibley

Amusing covers aside, there were some practical reasons for the Eye’s continued sales success. Firstly, Hislop’s commercial colleagues negotiated new deals for the magazine to be sold in supermarkets, which remained open through lockdown. And secondly, loyal readers who were struggling to find copies of the magazine started taking out subscriptions. The result is that Private Eye now has around 175,000 subscribers – more than ever before.

Some readers, says Hislop, suggested that he should have introduced a digital edition.

“And I think at that point I didn’t realise, but I do now – everybody spent so much time on screen in lockdown, the last thing they want is something else on screen. So a hard copy publication that you can sit in a chair – not on your screen – and read suddenly turns into a sellable item.”

Private Eye, which is privately owned and has around 15 full-time staff and numerous contributors, plays its business cards close to its chest, rarely disclosing revenue and profit figures. Companies House accounts for 2015 report an annual turnover of around £7m.

Read more: The new Trump bump: How Newsmax CEO Christopher Ruddy and far-right outlets are taking on Fox News

BBC at risk from ‘vindictive’ government

The last time I interviewed Hislop, in 2015, the BBC was facing budget cuts at the hands of David Cameron’s government.

With the government planning to make the broadcaster cover the cost of free TV licences for over-75s, a group of actors, presenters and writers signed an open letter – dubbed the “luvvies’ letter” – that called on Cameron to ensure the BBC was not “diminished”. Hislop, one of the corporation’s biggest stars, revealed he had declined to sign the letter – saying that doing so would have made him look like an “overpaid wanker”.

Five and a half years on, and Boris Johnson’s Conservative government has reportedly considered proposals to decriminalise non-payment of the licence fee. There have also been suggestions the licence fee could be replaced altogether with a Netflix-style subscription system.

This time, Hislop appears to be taking the threat more seriously.

“I think they’re vindictive enough to make it very difficult for [the BBC],” he says of Johnson’s government.

“I mean, I think all the governments that I’ve ever covered have been cross with the BBC. The Blair one – if you remember the Alastair Campbell years – they were incandescent at any criticism of themselves. So that was quite a dangerous time. [Theresa] May, you know, not so much. [Gordon] Brown, whatever.

“But this lot have got it into their heads that it’s part of the culture war and the BBC is ‘woke’ and hopelessly biased. I mean, God, if the BBC’s hopelessly biased then an 80-seat landslide [in the 2019 election] – I’m not quite sure how that happened then. It shows how ineffective it is if it is [biased]. Which I don’t believe anyway.”

Hislop describes the current government as “more dangerous” than previous administrations “because they wrap it up in a sort of: ‘It’s a free market thing. It’s a move to the future. It’s unfair to have a licence fee. Everyone gets their stuff digitally.’”

Hislop believes that comparisons between the BBC and Netflix or Amazon Prime are unfair.

“It’s a ridiculous comparison that they use: what you get out of the BBC for that money and what you can get from a streaming service. It is ridiculous. But it makes a lot of headway.

“And I think they will try and use that to weaken the BBC. And that’s bad news, I think. And that’s not just because they pay me.”

The cost of a streaming service, he says, “hardly, let’s be honest, covers the Proms, BBC’s choirs, the regional orchestras, all the local news channels, the website”. He also highlights free lessons the BBC is running for children during lockdown – “I mean, I don’t think Netflix is going to do that”.

He adds: “Big streaming [companies], they’re not going to put on Paul Whitehouse goes fishing with Bob Mortimer – which is going to be one of my greatest pleasures of the entire lockdown. I don’t see them doing it. I don’t think we should ignore what we have because there’s a very strident cry of, ‘Ooh, it’s the BBC, let’s get rid of it.’”

So your position has changed a fair bit since 2015 when you refused to sign the “luvvies’ letter”?

“I still wouldn’t sign a letter because I don’t think a letter from me persuades anyone of anything really,” he says. “But you asked the question, I’m perfectly happy to answer it.

“You know, I still am an overpaid wanker. That’s not in dispute. But I think the argument about the Beeb is probably better put by other people. But there we are.”

Read more: Private Eye draws on Blitz spirit after unexploded WW2 bomb threatens print deadline

Ian Hislop vs Piers Morgan

As the editor of a magazine that likes to challenge (and often mercilessly tease) establishment figures, Hislop has inevitably made some enemies over the past 35 years.

One of his most prominent foes is Piers Morgan, the former Daily Mirror editor who is now a host on ITV’s Good Morning Britain. Morgan has called Hislop an “annoying little gnome” and far worse.

What’s the story?

“I had a long feud with Piers,” says Hislop. He believes the animosity has its roots in Private Eye’s coverage of his “less than distinguished journalistic career”. He also points to a “car crash” appearance Morgan made on Have I Got News For You. (“Someone at the Mirror told me they used to play it on a loop at their Christmas party because it was such a pleasure.”)

The pair’s “bad blood” escalated when Morgan’s Mirror ran an open campaign against Hislop that sought to dig up dirt on the Eye editor. “He sent journalists round my village!”

How long did the investigation last? “Ages. And, you know, he rang up Friends Reunited, anyone I’d been at school with. [He] slightly missed the tenor of some of my friends. There was one, someone rang up and said, ‘I’m from the Mirror. I’m looking for, you know, just anything on Ian Hislop. I gather you were at school together. Is there anything you’d like to say?’ And this friend said: ‘Fuck off.’”

Did you take the investigation into your stride or did you find it upsetting?

“It was quite extraordinary,” says Hislop. “I mean, I think it’s one of the funniest episodes of my life now. I mean, my vicar rang me up – I’m always telling this story – and he said: ‘I’ve had someone on the phone saying: Have I confessed anything good?’”

Are you friends now? “I haven’t seen or spoken to him so I have no idea. But the truth is that his breakfast show and his harangue of [Health Secretary Matt] Hancock or [Home Secretary] Priti Patel the other day – they’re pretty good.

“So, you know me, I like to take things as they are, and if events change then I change my mind. And I think he does a pretty good job… Don’t put that bit in.”

In fact, it turns out, Morgan last year tweeted his support of Hislop for a section on Have I Got News For You in which he condemned Dominic Cummings, the Prime Minister’s former chief adviser, for breaching lockdown rules.

Enjoying Ian Hislop absolutely lacerating Dominic Cummings on #hignfy. There, I’ve said it.

— Piers Morgan (@piersmorgan) May 29, 2020

National treasure? ‘Oh no!’

Hislop’s criticism of Cummings was not to everyone’s taste (the BBC had to reject some viewer complaints about it). But overall it appeared to capture some of the frustrations of the nation in 2020.

Search ‘Ian Hislop’ on social media and you’ll find dozens of posts praising him either for his Cummings rant or for his 2014 Question Time debate with Priti Patel (now the Home Secretary) on capital punishment.

Several Twitter users even describe Hislop as a “national treasure”…

“Oh no!” he squeals when I tell him this. Private Eye has run several columns down the years poking fun at the media’s overuse of this title.

Do you think you’re a national treasure? “No,” says Hislop. “But presumably you made that up and put that in.”

No, I tell him, quite a few people have said this on Twitter (Hislop does not use social media). How does that make you feel? Does it make you cringe?

“Yeah,” he says. “It makes me feel slightly worried. I mean, you put national treasures in museums and then ignore them.”

Does Hislop consider himself to be woke?

“No. I hate the phrase. Because I think it just becomes something the Daily Express attaches to things they don’t like.

“It seems to me the equivalent of, for my generation, someone’s uncle saying, ‘Well, I don’t want to be politically incorrect…’ and then saying something appalling.”

He adds: “I find the woke thing is a bit of a flag. I don’t like the word. I’d rather go for each issue as it was. I think the culture wars are an attempt to make everything bi-partisan again, to divide everything along the same old lines. And I don’t see those lines.

“Personally, five years ago, probably when you first interviewed me, you’d probably have found most people saying, you know, ‘What a boring, smug little Englander he is, making programmes about parish churches and trains – what a bore he is.’

“Nowadays I’m the smug, liberal, metropolitan Remainer. I don’t feel I’ve changed.”

From scraps of paper to Dropbox in two weeks

Before March last year, Private Eye was edited and produced in an old-fashioned manner using cardboard and scraps of paper on a large table in the Eye’s Soho studio.

Glenn Orton – the magazine’s studio manager, who I spoke to after my interview with Hislop – says: “When people see – people who have worked at other titles – they’re amazed. It’s archaic, but it functions.”

He adds: “Of all the places I’ve worked, I’ve never come across anywhere that worked quite like this. But the beauty of it is, working like that, Ian can edit faster – with a few bits of paper on the table, moving them around. You know, the Eye’s got lots of small stories. All those little stories are put together on a Monday afternoon or a Monday evening. So it’s all moved around very quickly.”

Orton’s challenge, come lockdown in March, was to find a way of “recreating that opportunity for Ian to move things around quickly, but doing it digitally”. The Eye’s team now communicate over Slack (they also have a Whatsapp group), use Dropbox to share files, and Orton and Hislop put the magazine together on InDesign.

What will happen when Eye employees are allowed to go back to the office? Orton says: “Depending on how Ian wants to work, I think we’ll probably go back to a percentage of the old way.”

Counterintuitively, the move towards a more technological process has actually slowed down production.

Adam Macqueen, an Eye journalist who contributes heavily to the magazine’s coverage on media (Street of Shame) and politics (HP Sauce), explains via email: “The biggest practical adjustment has been that all our deadlines have had to be reeled back because the production side takes so much longer, which means we’re now having our press day editorial meeting – which used to be on Monday morning – on Sunday.”

He adds: “I think Private Eye, which has never been the most cutting edge of offices, fast-forwarded through about 20 years’ worth of technological change in two weeks last March. But from the hacks’ end at least, it seemed to work seamlessly – and that’s largely down to Glenn.

“Effectively nothing had changed for us, in that we were still just emailing our copy to the subs – but beyond that stage, everything was thrown up into the air and rearranged beyond recognition, and it seemed to work perfectly.

“There was one story about Iain Duncan Smith that went in twice in that very first WFH issue. But it was a good story so that was okay.”

The larger issue for reporters was the enforced end of the Eye’s legendary lunches. Hosted fortnightly at the House of St Barnabas (and formerly at the Coach and Horses), the gatherings were a regular source of gossip and stories for the Eye’s journalists.

How does the magazine operate without them? Hislop says: “It’s very different, you can imagine, on Zoom saying to somebody, ‘Got any stories?’ [Rather] than slightly inferring at the end of a long lunch… ‘Have you got any stories?’”

Macqueen says: “My main worry is the stories that are falling through the cracks. If someone wants to get a specific piece of information to me they have plenty of ways to do that – and they certainly have been – but I feel I must be missing all sorts of stories that contacts don’t know I don’t know, and that you usually pick up in conversation over lunch or a drink.

“Not having the fortnightly lunches has been a real blow. A good proportion of the stuff I’ve always done for Street of Shame and HP Sauce comes from conversations where I’ve gone, ‘Hang on, rewind a second, what did you just say?’, as well as the stuff they’ve actually set out to tell me.”

How long will you stay at the Eye? ‘It depends how this interview goes down’

With time running out, I finish off my Hislop interview with some quickfire questions about life at Private Eye and the editor’s future at the magazine.

Have you lost many friends because of coverage in the Eye? “Yeah. But I didn’t have a lot.”

What recent Private Eye story are you most proud of? Hislop points to the Eye’s “absolutely brilliant” coverage of technological errors that led to Post Office employees being falsely accused of – and in some cases falsely imprisoned for – stealing money.

Do you still have to deal with lots of lawsuits (Hislop was once dubbed “the most sued man in Britain”)?

Yes, he says, but not for libel (the Defamation Act 2013 raised the bar on suing meaning litigants had to prove serious harm). Instead, legal actions tend to focus on privacy and commercial confidence nowadays.

“Everyone will tell you the libel law and the libel bar collapsed really because people don’t sue as much,” he says. “The laws were changed, partly as a result of a lot of our cases.

“And because of social media. So much stuff that’s libellous is out there on the net [now] that people are… more used to thinking: I’ll let it run or whatever.

“The things we get are: ‘You are not allowed to run this because it’s commercially confidential.’ So as soon as the government outsources anything interesting, you’re not allowed to write about it. Which we waste a lot of time and money on.

“And then if you do write about individuals, they tend not to say, ‘this isn’t true,’ they just say: ‘This is private.’”

These legal complaints, he says, are “certainly less public” and rarely make it into open court.

“It just seems to me you never really get the chance to argue,” he adds. “There’s more activity, but you see less of it.”

Do you ever think that Private Eye and Have I Got News For You have made the British public too cynical?

“I hope not. It’s not a bad question. People say, ‘Well, it’s your fault. You undermine various narratives and then you find that people don’t believe any.’

“I’ve never advocated that nothing is true and that there’s no point in believing anything.”

Finally, how much longer do you think you’ll be editor of the Eye?

“It depends how this interview goes down, I should think,” he jokes. “I’ve no idea. I’ve occasionally made suggestions about how long I’d last and they’re all wrong.”

So a while yet?

“Yeah, I mean, certainly I’d really like to feel I’ve got the Eye through this, if not intact then certainly in some reasonable shape. And then I’d start thinking, I think.”

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog