In 2016, between his resignation from Politico and the founding of news startup Axios, Jim VandeHei caused a stir in the digital media world by accusing several peers of falling into the “crap trap” – “mass-producing trashy clickbait so they can claim huge audiences”.

Four years on, and the journalist-turned-entrepreneur is happy to report that the “crap trap” is largely behind us, in part because clicks weren’t translating into cash.

Unfortunately, in 2020, Axios’ chief executive has identified a new – potentially more significant – issue for the news industry to overcome.

“If we had a ‘crap trap’ crisis before, we have a truth crisis today,” he tells Press Gazette. “So the problem four years ago was an abundance of shit. Now it’s an abundance of people who should believe truth who don’t believe truth. So I think that’s the new problem to solve.”

He blames social media for “eroding a lot of people’s capacity to sort fact from fiction”, and believes the platforms, as well as governments across the world, need to do more to address the issues.

But ultimately, he adds, internet users themselves need to take more “personal responsibility” for the content they consume.

“At the end of the day, I choose whether I smoke. I choose whether I drink. I choose whether I ingest shit content into my mind on a daily basis,” he says.

“I choose whether I not only ingest that shit content. I choose whether I share that content without even reading it, and only sending it because I got some kind of dopamine high off of the headline or the photograph that was attached to said piece of content. And so there has to be personal responsibility in that…

“No politician is going to want to tell people to suck it up and figure it out yourself. But I’m telling you, until government and the companies do more: Suck it up and deal with it yourselves.”

He adds: “The God’s honest truth is that if you want you could very easily, as an individual, create almost a bionic mind. You could be so much smarter than you ever dreamed possible if you allocated your mind time correctly. If you realise there’s more good content than at any point in humanity.

“Where do I get that content? Where’s that content delivered most efficiently and effectively? Hint: Axios.”

The Axios antidote to a ‘broken’ media system: ‘Smart brevity’

VandeHei, originally from Wisconsin, started his career as a journalist, rising to become a congressional and White House reporter for the Washington Post before co-founding political news operation Politico in 2006. As chief executive, VandeHei helped Politico establish itself as one of Washington’s major news outlets.

In January 2016, shortly after Politico had expanded into Europe, VandeHei resigned from the company at the same time as chief White House correspondent Mike Allen and chief revenue officer Roy Schwartz.

Over the following year – a period in which VandeHei put out his “crap trap” thesis on The Information – the trio developed the idea of Axios, which they launched in January 2017.

In addition to the “crap trap”, they identified several other issues with the news industry upon launch. “Stories are too long or too boring,” the Axios manifesto states. “Websites are a maddening mess… Readers get duped by headlines that don’t deliver and are distracted by pop-up nonsense or unworthy clicks. Advertisers don’t get the quality attention they deserve.”

One of the key problems, they suggested, was that digital media companies were producing “journalism the way journalists want to produce it, often long-winded pieces that take too long to get to the point”.

Launching with the slogan “smart brevity”, Axios set itself the goal of delivering “the clearest, smartest, most efficient and trustworthy experience for audience and advertisers alike”.

The simplest demonstration of its approach can be seen in the way it reports stories. Articles break the conventions of traditional news reporting, using bullet points and bolded font to make it easier for readers to grasp important facts.

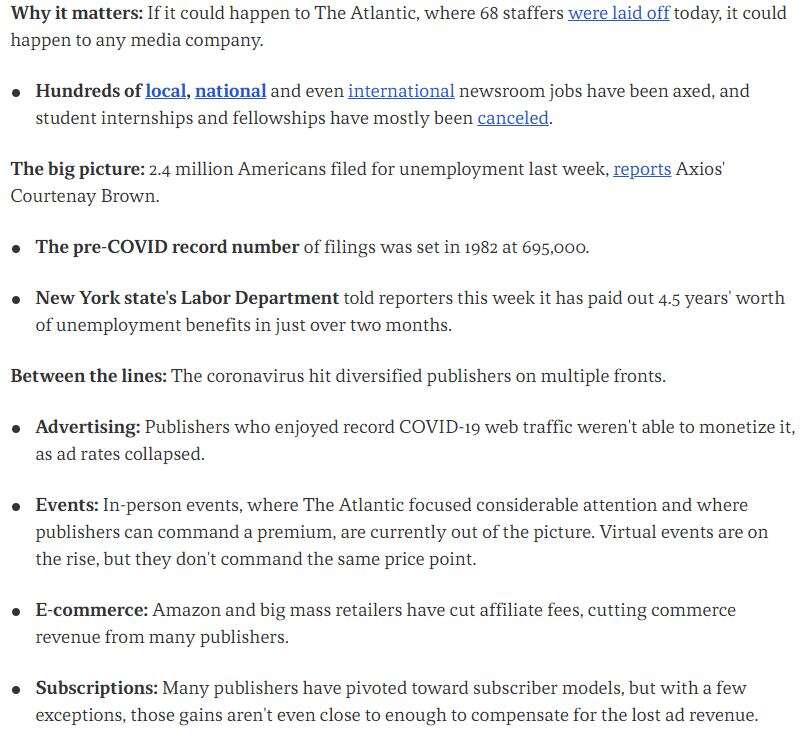

Example of Axios story formatting:

“We’ve shown that there’s such a value in brevity, in being able to make information consumption way more efficient and in the beauty of simplicity and design,” says VandeHei.

“People’s minds are cluttered. If you can save them time and not give them all these flashing lights, and all this garbage that they didn’t need, there’s a reward for it… People crave simplicity, efficiency, stuff that they can trust in a clean place.”

How Axios beat the Covid-19 ad market collapse

Nearly four years on, and Axios – like Politico – has established itself as a major force in the US news industry. Its free-to-access website attracted 19.8m unique users last month, up from around 7m the year before, according to ComScore figures. It also claims to have 1.4m individual subscribers to newsletters that cover its various speciality areas, which include politics, technology, business, media, the environment, healthcare and science.

In addition to its website and newsletters, Axios also has its own TV series on HBO. In August, Axios on HBO broadcast one of the most memorable interviews of Donald Trump’s presidential career (see below), which was reported on by media across the world.

.@jonathanvswan: “Oh, you’re doing death as a proportion of cases. I’m talking about death as a proportion of population. That’s where the U.S. is really bad. Much worse than South Korea, Germany, etc.”@realdonaldtrump: “You can’t do that.”

Swan: “Why can’t I do that?” pic.twitter.com/MStySfkV39

— Axios (@axios) August 4, 2020

Axios, which today has around 200 employees, also appears to be in good financial shape. The company says it is profitable and is expecting to increase its revenues by around 30% to $58m this year.

This growth comes despite the fact Axios does not have a subscription business – although VandeHei has spoken about introducing one in the future – and derives around 80% of its revenues from advertising. Other news businesses have seen their ad income battered this year amid the economic crisis brought on by Covid-19.

VandeHei admits that he was expecting Axios to be badly affected by the advertising slowdown, and that the business received a $4.8m loan from the Paycheck Protection Program in the US. But the predicted hit never came, and Axios was able to return the money.

The bulk of Axios’ advertising revenue comes from newsletter sponsorships, rather than from display advertising.

“It’s important to understand our advertising space versus most others’ advertising space,” says VandeHei. “Companies that advertise with us advertise because they care what smart, curious people think about their company or their brand beyond making money. They want people to know the social causes they’re involved in, the good that they do in the community, or the big topics they’re trying to tackle as a company that go beyond just making money… They also want to recruit good, talented people, and they want those people to see they stand for something beyond profit.

“That’s been a really high-growth market,” he adds. “We’ve not seen a pull-back in that area. If anything, we’ve seen companies spend more than ever. So it’s different than the typical advertiser in the New York Times and certainly in a glossy magazine.”

Can Axios make local news pay?

At the beginning of next year, Axios is embarking on a new challenge: local news. It will be launching two-person newsletter teams for Denver, Des Moines, Minneapolis and Tampa.

Local news in the modern era is a tough nut to crack. Research suggests that between 2004 and 2018, almost 1,800 local newspapers closed across the US, while many others have fallen victim to the coronavirus crisis.

VandeHei does not underestimate the challenge, but is hopeful that Axios can make it work.

“We think there’s an opening as it’s clear people want to know what’s going on in their community,” he says. “They want to know what’s happening in business, in technology, in the education system and politics. It’s just that often they don’t have often a hell of a lot of ways to do it. Or if they do, they tend to be still delivered in a daily conventional or traditional way that might not naturally comport with their new habits since they’ve been spending so much time online, so much time on social media. So we think there’s a real opportunity there.”

VandeHei says there is an “altruistic” aspect of Axios’ planned foray into local news. “It’s an important puzzle that needs to be solved,” he says. “I do think if you don’t have good coverage of states and cities, bad things happen. I think having people educated and aware is really important for democracy.”

But, he adds: “We wouldn’t do it if it was just important for democracy and we thought it would be terrible business. We think it can be important for democracy and good business.”

Axios plans to use its existing infrastructure – including newsletter distribution tools, marketing capabilities, existing audience base, advertising department, technology, and its copy editors – to keep costs low in local areas. VandeHei is also confident this setup could help make the business scalable beyond the cities of Denver, Des Moines, Minneapolis and Tampa if the experiment proves successful.

“If it works in four, it might work in 400,” he says. “If it works in 400, now you’re on to something. You might have one hell of a big business.

“And so that’s what it is. We might fail. We always go into these things eyes wide open. Most new things fail. “

Can VandeHei succeed where others are failing? The odds would appear to be stacked against him. But his track record of success with Politico and Axios as a national news outlet offers some encouragement.

“The whole idea of being an entrepreneur, of being a creator, is that there’s a certain amount of risk in it,” he adds. “But this feels like a pretty wise, calculated risk with a pretty nice upside.”

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog