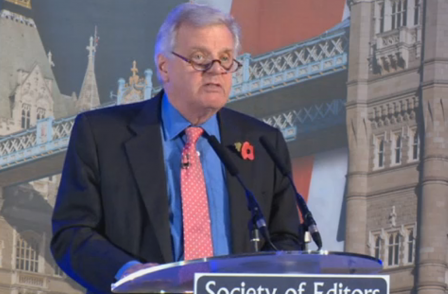

Former chairman of both the BBC and ITV Lord Grade has said that swift introduction of the new Independent Press Standards Organisation presents the best way for the UK press to restore confidence in the wake of the hacking scandal.

Delivering the Society of Editors lecture at the group's annual conference today he delivered a robust condemnation of the Royal Charter on press regulation signed into law by the three main political parties.

And addressing the main "stick" encouraging publications to sign up to the regulator, the threat of exemplary damages, he quoted an opinion from Lord Pannick QC suggesting that such damages would be against European law.

Grade began his lecture by asking "where did it all go wrong" adding: "How did politicians allow themselves to be so comprehensively hijacked by a well organised lobby group? How on earth did the press allow itself to be put so firmly on the back foot? How did so many people get bamboozled into confusing voluntary, self-regulation with statute? How did we all allow the debate to end with the wrong answer to the wrong question?"

Grade condemned the way in which the press regulation Royal Charter was agreed, in a late-night deal in March this year, saying: "That final session, where politicians of three main parties huddled in secret over pizza with Hacked Off in the room to agree the final draft of the Royal Charter, while the industry directly affected was unrepresented – that session was, to say the very least, counter-productive…

"So is it really different this time? This time, is the press really condemned to live under the shadow of statutory regulation on the one hand, or bankruptcy in the defamation courts on the other?"

Answering his own question, Grade said he had received eminent legal opinion that the exemplary damages threat, as laid out in the Crime and Courts Act 2013, was a badly-drafted piece of legislation.

Grade said he had sought advice from Lord Pannick QC who told him: "My view is that it is a breach of Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights to penalise by exemplary damages those newspapers who refuse to sign up to the official – Royal Charter – regulator.”

Grade said: "The protection from exemplary damages supposedly offered by the Royal Charter may well turn out not to be a nice carrot but rather more a dead parrot."

Grade (who is himself a former member of the PCC) put forward a detailed argument about why he believes IPSO is a tougher regulator than the Press Complaints Commission and urged all publishers to sign up to it.

He said: "The next 12 months or so is going to be tough for the press. The current Old Bailey trials will keep the misdeeds of some newspapers firmly in the public eye until the Spring.

"And once those trials are over, Sir Brian Leveson will begin part two of his inquiry – surely not? But it is always good to have something to look forward isn't it?

"Like it or not, all this will undoubtedly cause further damage to public confidence in the industry.

"Against this relentlessly downbeat mood music, IPSO is the best chance the press has to show it means what it says about changing its ways for the better."

With The Independent, FT and Guardian Media Group all yet to decide whether they will sign up to IPSO – Grade said it would be a "catastrophe" if major publishers do not sign up to IPSO.

Evan Harris from Hacked Off said that the press industry would continue to control the new regulator via the successor body to Pressbof, the Regulatory Funding Company, thus repeating the main failing of the PCC (that it was not independent enough).

Grade said: "What we need to do is get on with this now..we can sit and negotiate for ever, the public needs action. Your points of view are well argued and well made and should be taken account of, but let's not stop the process and you can continue to press for the changes which you think make it more fit for purpose."

Lord Grade – Society of Editors Lecture 2013, in full

My text today is taken from the book of Oasis, and the question put therein by the prophet Gallagher, Noel: “Where did it all go wrong?”

When you look at the mess that more than two years of intense debate over press regulation has produced, you do have to ask yourself that question.

How did politicians allow themselves to be so comprehensively hijacked by a well organised lobby group?

How on earth did the press allow itself to be put so firmly on the back foot?

How did so many people get bamboozled into confusing voluntary, self-regulation with statute?

How did we all allow the debate to end with the wrong answer to the wrong question?

And, most pressing of all, where do we go from here?

I should begin by declaring an interest – in fact a number of interests.

Since April 2011 I’ve been an independent member of the Press Complaints Commission. In case you’re wondering, that’s the body now universally known as the, quote, discredited and toothless Press Complaints Commission” unquote – something I’ll say more about a bit later.

For now, though, let me make clear that the opinions in this lecture are entirely my own.

But beyond my role in the PCC, I have other interests to declare.

Over the years I have found myself on both sides of the media – as reporter, as publisher and, indeed, as target.

I know from personal experience what it’s like to be picked over and mauled by the press. I’m pretty sure that my obituary in the Mail will begin with a reference to their description of me as “pornographer in chief”. That description, you’ll recall, was coined by columnist Paul Johnson. A spanking good phrase, too, if I may say so…

It’s happened to me more than once over my family and personal background – on one occasion reducing me to tears. It gave me some sense of what it’s like to be picked over by a pack of hacks on the scent of a splash.

Of course my experience was nothing compared to the pain Millie Dowler’s family was put through in their grief. Nor to the suffering inflicted on far too many individuals by journalists willing to break the criminal law to get their story.

It certainly does at times seem as if tabloid journalists leave their humanity and their conscience at home when they head for the newsroom. You do wonder how some of them sleep at night.

And we should never underestimate the degree of genuine public revulsion this behaviour has caused. This is not something sexed up by Hacked Off.

The steady flow of opinion polls show that large majorities of the public support much tighter controls on the press. These are evidence that the public has dramatically lost confidence in at least some sections of the industry.

We may have ended up with the wrong answer to the wrong question. But we should never forget where this sorry trail began: with journalists behaving badly.

It was the resulting public outrage which, in turn, prompted the politicians to act. The press, in other words, has brought this situation on itself. And we have to keep that uncomfortable truth front and centre.

The trouble is, that as soon as the politicians became involved, they did what politicians always do: they reached for the statute book – always the wrong answer where press regulation is concerned.

When I was doing the research for this lecture I counted up how many government inquiries into the press there have been in my lifetime.

I was astonished to discover there have been no less than seven of them. Three Royal Commissions, two Reviews, one Commission, and now, with Leveson, a Judicial Inquiry.

Leafing through this mountain of paper, the astonishing thing about all these commissions and inquiries and reviews is just how familiar they all seem.

Indeed, the accuracy with which they foreshadow today’s debate is spookily uncanny.

They trample over the same well-trodden ground, grapple with the same well-trodden issues – and then produce much the same well-trodden results…not to mention the same sharply-polarised debate once the report is published.

And the ultimate result? Parliament has a brief flirtation with the idea of statutory regulation. But in the end the politicians back away. And the press is left alone, free and unfettered by new legislation.

Ah, but this time it’s different, we’re told. Things have changed. The lessons of history have been learnt.

Oh yes?

It’s true that there have been many exchanges in both Houses of Parliament and once again the calls for statute have always been louder than the voices defending press freedom. I can well remember the many recent exchanges in the Lords producing a clear majority pressing for a statutory element in the new regime.

“Parliament has spoken” has been the cry. Well, actually it hasn’t – for the record, there has been no specific vote in either House.

Anyway it’s true that once again the politicians have reached for the statute book. Indeed this time they’ve not only reached for it, they’ve actually drafted and sealed a Royal Charter and changed the law on exemplary damages in defamation cases to show that they really mean business.

Indeed, so eager were our elected representatives to show just how deeply they shared the public’s outrage, that they handed what looked like a veto on it to the unelected representatives of Hacked Off as they drafted.

That final session, where politicians of three main parties huddled in secret over pizza with Hacked Off in the room to agree the final draft of the Royal Charter, while the industry directly affected was unrepresented – that session was, to say the very least, counter-productive.

So is it really different this time? This time, is the press really condemned to live under the shadow of statutory regulation on the one hand, or bankruptcy in the defamation courts on the other?

Maybe. But maybe not.

Everyone was a bit taken aback by the speed at which the Royal Charter went through the Privy Council and the law on exemplary damages was changed. But that speed may well be their downfall.

Because, on closer examination, the results have about them the strong smell of a seriously ill conceived piece of Parliamentary draftsmanship. Which may explain why the Government now appears to be distancing itself from them.

More on that in a moment.

Let me make my own position clear.

I am opposed to statutory regulation of the press. The idea of politicians, themselves subject to press scrutiny, voting on and having the opportunity to amend statutory press regulation cannot be in the public interest.

The public interest is clearly best served by there being as little statutory interference in the press as possible, and, of course, the Press behaving responsibly.

The freedom of the press cannot be absolute, of course. And in Britain the law imposes some of the tightest restrictions found in any democracy. Laws on libel, on contempt, on official secrecy, on privacy, on hacking phones, on bribing police officers and other public officials. The list is long and the law is clear.

But within these bounds – and they are quite considerable – the press has to be free to publish what it considers to be in the public interest. Publish and be damned, as my first boss Hugh Cudlipp so memorably said.

Of course, having published, editors must be accountable publicly – through independent regulation and through the courts where necessary.

They must be prepared not only to argue the public interest in publishing, but also to defend the ethics of their news gathering. And, if found wanting, they should be punished meaningfully, and there should be effective remedies for their victims.

But all this can be achieved without the need for statutory regulation.

The current Royal Charter agreed by the three main parties with such approving noises from Hacked Off is a dangerous step too far.

It enshrines the principle that Parliament has the right – however remotely – to intervene in the regulation of the press. And that, to me, is a red line.

My key objection is that it gives Parliament not just a voice but a say in the regulation of the press. Parliament gets a say by voting. Imagine if a vote on press regulation had been going through Parliament at the time the Telegraph was exposing the scandal of MPs expenses?

Do you really imagine that MPs would have been able to restrain themselves from making their outrage felt in vindictive amendments and then in the voting lobbies?

It’s worth pointing out here that Parliament never votes on the BBC, even though it’s 100 per cent publicly owned.

Government decisions on the BBC Royal Charter and the level of the Licence Fee are debated – but never voted on. It’s a device that gives Parliament a voice but not a say in the affairs of the BBC and protects it from malicious amendments. It is this absence oif any vote that protects the editorial freedom of the BBC from political interference.

But as things now stand, Parliament will have more right to interfere in the editorial freedom of the press than it does in the editorial freedom of the BBC.

Bonkers, or what?

After 300 years are we really thinking of introducing a statutory element into press freedom?

When prime ministers are urged to raise human rights and free expression issues with various friendly and unfriendly foreign states, how can they expect to be heard if they have just eroded three centuries of freedom to publish within the law in Britain?

The Charter is not only unnecessary, but as I have already touched on, it depends for much of its practical effect on a piece of legislation that looks to be seriously faulty in its design.

The proponents of the Government’s Royal Charter make much of the so-called “carrot” it offers to the press in the form of protection from exemplary damages for those who volunteer to sign up for ‘their’ charter.

The implication of this is, of course, that those newspapers who don’t sign up will run the risk of incurring those exemplary – or rather, punitive damages.

In other words, there’s a carrot to attract the press, but there’s also a stick – potentially a very large and very expensive stick – available to beat up the press who don’t like the look of the carrot.

Now, this proposal is not found in the Charter itself, but in a piece of associated legislation. The relevant clauses were cooked up and tacked on to the Crime and Courts Bill 2013 shortly before it went onto the statute book a few months ago.

So this is now the Law. The Law of the Carrot and the Stick.

However, many fine legal minds question whether this section of the Crime and Courts Act will stand up to the scrutiny of the courts.

I sought advice on this point from Lord Pannick QC, one of the country’s leading experts in this field. His opinion was unequivocal. I quote from his note to me:

My view is that it is a breach of Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights to penalise by exemplary damages those newspapers who refuse to sign up to the official – Royal Charter – regulator.”

Article 10, by the way, is the one that protects freedom of expression.

Lord Pannick’s full opinion is, as you’d expect, wide-ranging and detailed. But let me just quote a couple of the key points he makes.

First of all, he makes the point that exemplary damages are anomalous in English Law – they have never been available in Scotland. The anomaly is that they bring the notion of punishment into civil litigation when damages are usually supposed to be about compensation. Judges don’t much like that.

And, crucially, he quotes a recent ruling in Strasbourg in a case involving a British newspaper where it was decided that the Human Rights Convention gives journalists special protection from punitive fines.

The ruling says that such punitive fines would, I quote:

…create a chilling effect…in…political reporting and investigative journalism, both of which attract a high level of protection under the Human Rights Convention.”

So there you have it. The protection from exemplary damages supposedly offered by the Royal Charter may well turn out not to be a nice carrot but rather more a dead parrot.

Let’s go back to where this all began – the Leveson Inquiry. Let’s remind ourselves what Sir Brian Leveson himself said when he published his report:

Not a single witness proposed that either Government or politicians, all of whom the press hold to account, should be involved in the regulation of the press. Neither would I make any such proposal….

…What is needed is a genuinely independent and effective system of self-regulation of standards, with obligations to the public interest.”

I believe we have this – or certainly the meaty bones of this – in IPSO, the proposed Independent Press Standards Organisation, put forward by a group of the major publishers.

IPSO, as you know, is the proposed replacement for the PCC, which has itself accepted that it should be replaced by a new body. In the meantime, the PCC continues to its work. But, in effect, time has been called on it.

I must say, I’m a bit sad about the ill-informed criticism it has suffered. Having seen the PCC close up and taken part in its deliberations I can vouch for the seriousness with which its takes its responsibilities. The invaluable service it offers the public must not be lost in any transition.

I think that the central problem with the PCC is that expectations have been laid on it which it was never set up to deliver. It’s sometimes described as the press regulator. But it’s nothing of the kind.

It’s a body that hears complaints about the press. Full stop. Describing it as the press regulator is a bit like describing the BBC Complaints department as the body that regulates the BBC.

It’s true that occasionally the PCC has made forays into activities that feel a bit like regulation – for example when it set out to investigate phone hacking allegations.

But since all this investigation amounted to was writing to editors asking had they hacked any phones, to which they all replied: “No”, and, er, that was it, this hardly counts as regulation in any form that any of us here would recognise.

And besides, you have to ask the question: even were the PCC properly constituted and funded as a full-scale regulator with serious investigatory powers, would it have made a scrap of difference in the phone-hacking saga?

I think not. This fact does not get nearly enough attention in the current debate presumably because it has become a convenient scapegoat – the Stephen Ward de nos jours.

Phone-hacking is a criminal offence, like burglary. You don’t deal with burglars by regulating them. You deal with burglars by banging them up.

Any journalist proven to be involved in hacking phones or commissioning others to do it, is breaking the law. Those doing it are prepared to risk going to prison – simply in order to scoop their rivals.

By the same token, bribing police officers is breaking the law. Any journalist who is proven to have done it, or commissioned others to do it, is breaking the law.

Now, if prison isn’t a sufficient deterrent, what sanction could any press regulator possibly deploy that might make journalists behave otherwise? Summary execution?

When Parliament set out to deal with a breach of the criminal law by asking themselves what Parliament could do to strengthen press regulation they were asking the wrong question.

It’s no wonder they came up with the wrong answer.

Honestly, I think there’s a lot of muddled thinking going on here. And that includes the expectation of what even very tight regulation of the press might actually deliver.

The BBC is heavily regulated. But that didn’t stop faked footage in a report on a UK retailer and alleged sweat shops in India. It didn’t stop Newsnight grossly libelling Lord McAlpine. Nor did it stop Newsnight failing to run its Savile investigation, which had the clearest possible public interest justification.

The most that regulation, in whatever field you care to name, can achieve, is to help reduce the amount of bad behaviour.

Yes, it can set out codes of good behaviour and, yes, it can impose sanctions on those who break those codes.

But even the tightest regulation can’t abolish bad behaviour. Maybe this audience should all be grateful for that. Because if bad behaviour were abolished, how would you all fill your newspapers?

The balance sheet of Newspapers in this country includes many negatives, but many more pluses.

The Sunday Times and Thalidomide; The Telegraph and the MPs’ expenses scandal; The Mail and its relentless pursuit of the killers of Stephen Lawrence; and the Guardian and its recent exposure of, er, phone-hacking.

Just a few of hundreds of real public interest examples to balance the grief caused by the News of the World, and maybe one or two other red tops.

But let’s not forget that the News of the World doesn’t exist any more. And let’s not forget that the press has accepted that things need to change and change drastically.

IPSO is tangible evidence of that. Their proposals include:

-

An independent appointments panel to select the members of the IPSO Board. The former President of the Supreme Court, Lord Phillips has agreed to oversee the selection of this panel

-

Both the IPSO Board and its Complaints Committee would have a majority of independent members. No serving editor would sit on either and there would be no industry veto on appointments

-

IPSO would have the power to require corrections and other remedial action

-

IPSO would have the power to investigate serious and systemic breaches even if no complaints had been made

-

IPSO would have the power to levy fines of up £1million

- There’d be an arbitration service; a system to stop harassment and intrusion by journalists; and a whistleblowers’ hotline to protect journalists put under pressure by their editors to break the code.

Hopefully, it will not place further financial strain and risk on the challenged Nations and regional press.

I have to say, this is a pretty impressive list. It’s certainly a valuable leap forward from the limited remit of the PCC.

I would add to that list a requirement on newspapers to publish their internal compliance procedures to be approved by the new regulator. It is the lack of internal compliance that has contributed to the current malaise.

The press has also accepted the idea of a layer on top of IPSO. A separate body called the Recognition Panel,albeit with no statutpory underpinning.

The role of the Recognition Panel is to make sure IPSO is doing its job properly and is properly accountable and independent of the press it regulates.

Now this all seems to me a pretty good result all round – a massive improvement on what went – or didn’t even go – before.

And Hacked Off has contributed greatly to this result and are to be congratulated.

Of course, we’re talking theory here, not practice. And we have to accept that the press does have a certain amount of form in promising reform but then failing to deliver.

But as a result of their readers’ concerns and the political pressures and, most important, the anguish of the victims channeled through the Hacked Off lobby, I really do believe the press has finally got it. IPSO is different. Although I also accept that we’ll only know if it is fit for its new purposes once we have seen it in operation.

The Culture Secretary, Maria Miller, has made encouraging noises suggesting that the Royal Charter could be rendered redundant if IPSO delivers what it says on the tin.

Now there are those who say the Charter is already redundant – an invitation to a party no-one is going to attend. But let’s not look a gift horse in the mouth.

The politicians should get behind IPSO, let's get it up and running as soon as possible. Let’s keep our minds open and let’s be prepared to tighten things up if experience shows it’s necessary.

That's enough debate ed, the public needs action this day.

The next 12 months or so is going to be tough for the press. The current Old Bailey trials will keep the misdeeds of some newspapers firmly in the public eye until the Spring.

And once those trials are over, Sir Brian Leveson will begin part two of his inquiry – surely not? But it is always good to have something to look forward isn't it?

Like it or not, all this will undoubtedly cause further damage to public confidence in the industry.

Against this relentlessly downbeat mood music, IPSO is the best chance the press has to show it means what it says about changing its ways for the better.

And then let’s all get back to the real business of producing great newspapers that inform, entertain, and hold the powerful to account on behalf of the public in the nations, in the regions and nationally.

We must always remember that the public interest has two sides: yes it is served by newspapers behaving responsibly and ethically and within the law but also in the end by being free from outside influence, especially that of the state.

“Have you got all that, copy?”

Thank you for listening.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog