In the first of a new Press Gazette series investigating the space where news and marketing meet, we take a look at the future of programmatic display advertising and examine whether it is working – for readers, advertisers and for publishers.

- To find out more about the future of marketing, download Lead Monitor’s white paper: B2B marketing after a pandemic: 8 key lessons for senior marketers

- Sign up for Press Gazette’s Marketing Matters email newsletter here

What are programmatic adverts and how can they be bad for publishers?

Visit the homepage of any large commercially-run news website today, and your screen is likely to be hit by at least one advert for a brand that is judged to be of interest to you.

More often than not, these are programmatic display adverts. The marketing content is placed there by adtech companies like Google, which fill similar slots across countless other websites across the internet.

The advertising that appears on a user’s screen is dependent on their demographic and interests – often worked out using data, or cookies, based on their web history. The exact adverts that appear are often determined by automatic real-time bidding, which takes place in the milliseconds between when a link is clicked and a page is viewed.

At their best, programmatic ads are perfectly targeted at web browsers, who find the marketing material useful or interesting and may click through to the advertising brand.

At their worst, seemingly irrelevant ads can negatively affect a reader’s experience on a news website, by clumsily obstructing content or slowing page-download times. For free-to-use websites with compelling content, this potential irritation may not be seen as a major issue.

But an increasing number of news businesses are now seeking to drive up online subscriber numbers. And this, according to David Chavern of US publishing industry body the News Media Alliance, is where awkward or invasive adverts can become a big problem for publishers. “People don’t want to pay for that experience,” he says of websites that bombard readers with programmatic display ads.

How the New York Times puts subs above ads

News businesses across the United States have for some time looked enviously upon the New York Times’ quarterly financial results, and its online growth figures in particular.

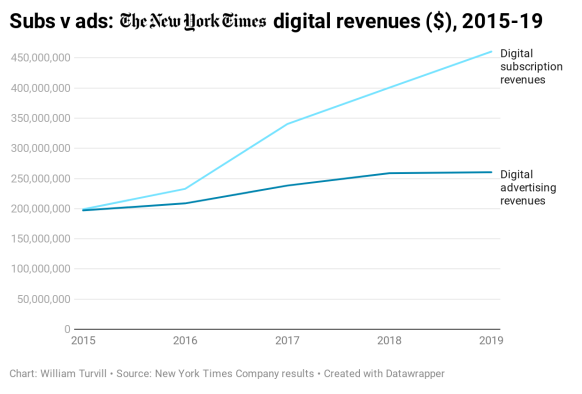

But their eyes have been drawn not to its online advertising revenues – which have performed solidly if not remarkably over the past five years – but to its fast-growing subscriber base. The NYT’s digital subscription revenues jumped from $199m to $460m between 2015 and 2019.

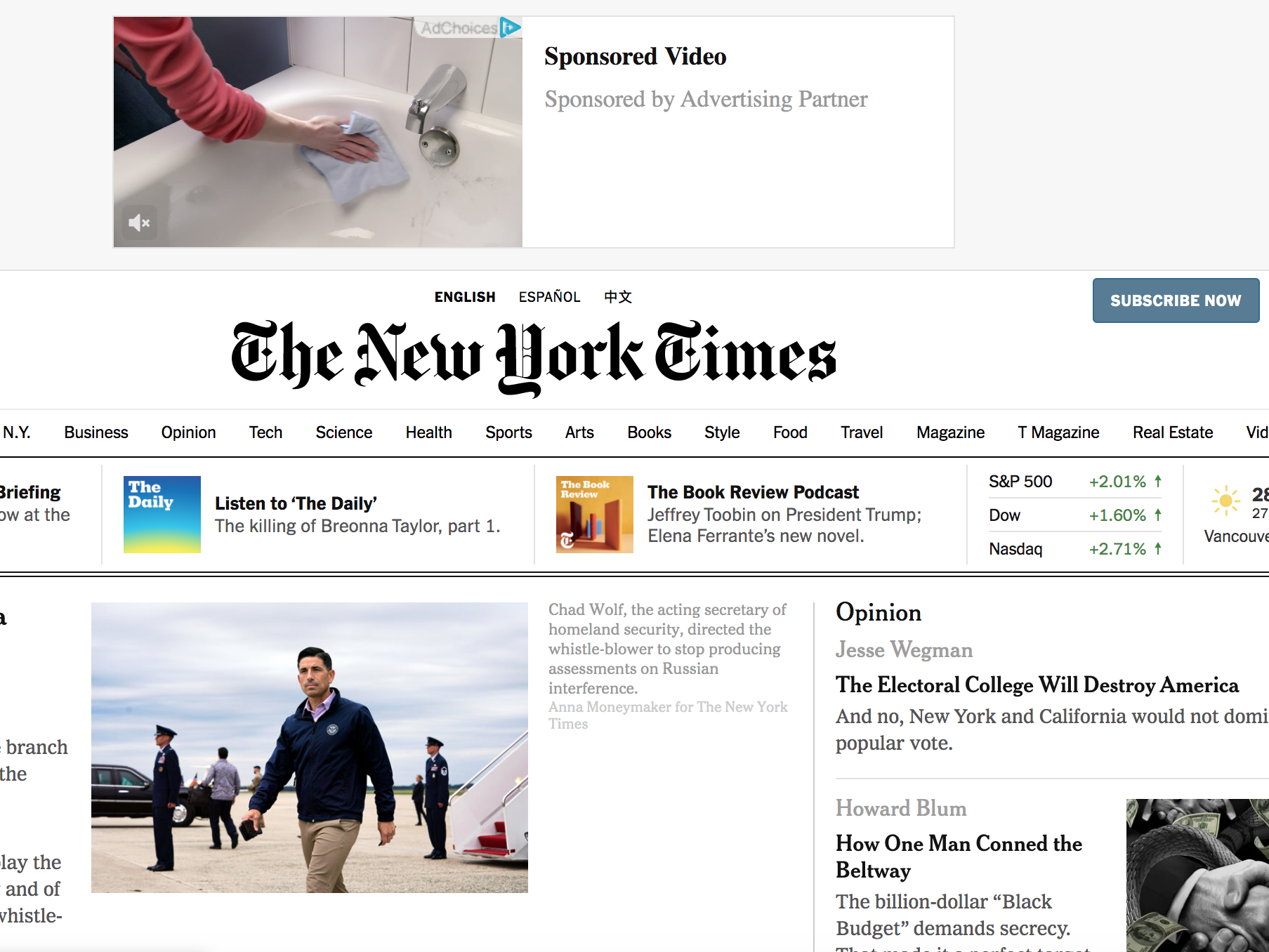

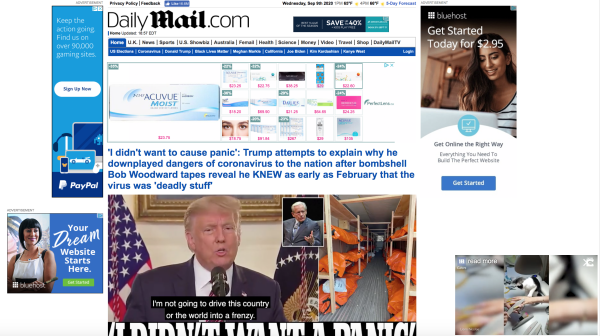

Online adverts remain an important revenue stream for the New York Times. But a comparison between the NYT’s website and Mail Online (below) shows that display advertising is less of a priority to the former.

The New York Times website on Wednesday 9 September, featuring one display advert at top

Mail Online website on Wednesday 9 September, featuring several display adverts at top

Underlining its subscriber-first approach, the New York Times last year openly sacrificed millions of dollars of revenues by removing open-market programmatic adverts from its apps.

Mark Thompson, who recently stepped down as chief executive of the company, admitted this would result in “the loss of digital advertising revenue in the single-digit millions”. But he said the company believed this would be “more than made up for by gains in engagement and a higher propensity by app users both to subscribe and retain”.

So is the NYT’s long-term business plan to build up a subscription business so large that it doesn’t need to worry about advertising revenue? No.

Speaking at a Goldman Sachs conference in September, the company’s new CEO, Meredith Kopit Levien, said that advertising remains an important part of the NYT’s future. In the long-term, she believes the company’s subscriptions – which currently number more than 6.5m – can be used to build an enhanced ads business based on “first-party”, rather than third-party, data.

What does this mean?

Currently, the NYT website – along with many others across the world – hosts adverts supplied by Google and other programmatic adtech companies. Under this setup, the NYT and others are reliant on Google – and the data it possesses, defined for publishers’ purposes as “third-party” because they do not own it – for online advertising revenues.

However, in the vision set out by Kopit Levien, the NYT would have enough information about its subscribers to be able to sell all of its own online advertising space without the need for “third-party” data.

“I think in the near term and over the last couple of years, what you’ve seen us increasingly do is really lean into the idea that we are a subscription business first, and we make a lot of choices with an eye toward that – about having a great user experience, having pages that load quickly, using data only in privacy-forward ways,” she told the Goldman Sachs conference.

“So in the short term, that does have some implications for the economics of the advertising. But over the long haul, we think it’s still a very important part of the economics.”

She added: “We in the last year have become far less reliant, and we’d like to get it to zero, on third-party data in advertising at the Times and selling advertising. And in its stead, we have built a really robust first-party data business that we use in privacy-forward ways.

“And I am very optimistic that we’ll be able to continue to grow the business, that that first-party data is going to be very effective – it already is – in helping marketers target in different ways. And I’m optimistic that that’s going to be a big part of the ad proposition at the Times going forward.”

Future of programmatic: US publishers losing interest in ‘random traffic’

David Chavern, CEO of publishers’ trade body the News Media Alliance in the US, says that many other American publishers have now come around to the view that the programmatic advertising system – and the ensuing fight for clicks – does not represent a viable future for them.

“While a lot of commentators like to extol the virtues of traffic, I’m afraid most news publishers have moved beyond thinking that random traffic is a particularly valuable thing,” Chavern tells Press Gazette. “They’re not into clickbait any more – they’re not trying to just drive random traffic to their sites.

“I think what we’re seeing is the slow death of the view that random traffic is valuable. Which, by the way, is what a whole number of businesses and industries were built on for years – this idea that random traffic is a goal.”

He adds: “In traditional print publishing, scale was the winning attribute. If you sold 10,000 more papers today than yesterday, then that’s 10,000 more papers better. Or if you double your circulation, that’s twice as good.

“And really that’s an old, old idea that somehow got [transferred] over into the internet. And all these people, who claimed to be very innovative, embraced this idea of scale and reach. And that facilitated all the clickbait stuff.

“But it’s interesting to me how long it takes that idea to die out, even though you make less money from it every year.”

He describes the programmatic advertising system as “broken”, and suggests it is about to become even more damaged by the “death of third-party cookies”.

In January, Google announced that it would be ending support for third-party tracking cookies in its Chrome browser within two years. Apple announced a similar move for Safari in March, and is also planning on allowing users to block tracking technology on apps across its devices. The plans have enraged both Mail Online and Facebook.

“That programmatic targeting machinery is all built around third-party cookies, and those are going away,” says Chavern. “They’re going away quickly with Apple, and then the Google Chrome announcement taking them away will essentially break that system.”

New Statesman removes all programmatic advertising

Some UK publishers have begun to shift their priorities also. Website traffic growth is still welcome, but the focus now is attracting the right kind of reader, i.e. one that may be persuaded to pay for an online subscription or who is highly relevant to particular advertisers.

Among those hoping to grow their subscriber base is Press Gazette’s sister publication, the New Statesman. In July, it announced it would be removing all network advertising from its website.

Martin Ashplant, New Statesman Media Group’s chief product officer, believes the prevailing online advertising model is broken. He says the display advertising system does not work for advertisers, readers or publishers – because “the revenue that you can generate from a scale-play around digital advertising does not pay for high-quality journalism”.

Ashplant believes the New Statesman’s commercial model shake-up, including a more targeted approach to advertising, will benefit the publication in several ways.

The group and its journalists will, for example, be able to focus on growing their “target audience rather than reaching as many people as possible regardless of who they are”. He adds: “One of the problems as I see it is that because that system is set up to reward scale, it naturally means that publishers have been seeking to grow page views rather than focusing on who is the right audience.”

He also believes the move will result in a better user experience and, as a result, persuade more readers to subscribe.

Ashplant – formerly of Metro and City A.M. – acknowledges that the current display advertising system works for some bigger publishers.

“You’ve got room for manoeuvre at the extremes,” he says. “So where you are massive, and you can generate those really high levels of scale, and you can spend a lot of money, there is opportunity.

“And equally where you can do things very cheaply – so if you are a viral content site where content can be created very cheaply with very few journalists and without massive overheads – you can make decent profits.”

But he adds: “What we’ve been seeing play out in the last few years, though, is that for everyone in the middle – which is the vast majority of publishers, including us at New Statesman Media Group – this is not a model which can fund quality journalism.”

The New Statesman’s website, captured on 9 September 2020, displays one small advert for a subscription to its journalism

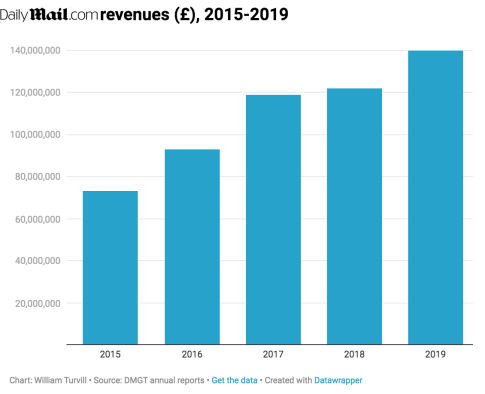

A good example of where the system does appear to work is Mail Online.

Funded almost entirely by online display advertising, the website’s revenues doubled between 2015 and 2019, from £73m to £140m.

Brand safety and programmatic advertising

Claire Atkin is the Canada-based co-founder of Check My Ads, a group that works with large corporations to protect ‘brand safety’ by advising them on how to avoid their marketing material appearing alongside disinformation and hate content.

She believes the current programmatic display advertising system does not work well enough for publishers or advertisers.

“Programmatic advertising campaigns are inefficient,” she tells Press Gazette. “They are wracked with fraud and useless ad placements. But worse than that, they often end up funding organisations that spread hate and disinformation. That’s bad for our communities, and bad for our brands…

“Marketers don’t want to fund hate organisations. We don’t want to fund Covid-19 disinformation. Advertising technology companies need to make it easier for us to control where our ads go. ”

Atkin also believes the model is bad for publishing and for public-interest newsgathering.

“This system is also a disaster for the news,” she says. “Ad exchanges pit news sites against every other website on the internet and get them to compete for clicks. When you have [Canada’s] Global News fighting for clicks against a bunch of viral kitten videos, that’s going to take away money from Global News.

“That’s bad for most marketers too, who want to get attention with their ads. The best place for that is the news.”

In defence of programmatic advertising

Programmatic display advertising remains a major revenue stream for many publishers.

According to 2019 report from Zenith Media, around two-thirds of digital advertising through banners, online video and social media is now programmatic.

The chart below, from the Zenith report, shows how global programmatic display adspend worldwide grew from $4bn in 2012 to more than $100bn in 2019. The chart also shows how its significance in digital advertising spend has grown.

Matthew Boisjoli, director of digital marketing at advertising agency King and Partners, recognises the issues publishers have with the programmatic system, but argues that it works well for many brands.

“From an e-commerce standpoint, the current model does actually work in a lot of ways,” he says. “There’s so much data and analytics available that you’re able to quickly scale up media for people to help companies grow revenues.”

The problem for publishers, he acknowledges, is that much of this data is owned by Google and Facebook.

“The biggest trend change in recent years is that it used to be more about where you were buying advertising,” says Boisjoli. “So, for example, you would really pay a premium to be on a specific site, or you would pay a premium to be associated with a specific publisher or platform.

“But now it’s totally switched because you can track a user across multiple web properties, you can track them across mobile to desktop, and obviously with Facebook and Google they can identify users pretty much anywhere.

“And so it becomes more about targeting a specific customer versus really wanting to pay a premium to be in Time magazine or a specific publisher. That’s a huge change over the last five years.”

Peter Mason, the co-founder of contextual advertising firm Illuma Technology, also comes to the defence of programmatic ads. And he believes the decline of third-party cookies – highlighted as an area concern above by Chavern of the NMA – presents an opportunity for publishers to make better use of programmatic.

“Programmatic is having to move away from a buy ‘em cheap, audience-chasing approach and look for smarter tools which consider context and mindset,” he said.

“In our case, the contextual algorithms favour long-form content, so they naturally drive revenues back to quality publishers.

“Some publisher groups are even developing their own advanced contextual solutions. For example, the New York Times now gives advertisers the option to buy against ‘perspectives’, ‘emotions’, ‘motivations’ or ‘trends’.

“If publishers choose smart tools which allow them to maximise their editorial content and their first-party data, they’ll be in a strong position to continue generating income from display advertising.”

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog