First takeaway of Breaking the News at the British Library: journalism is a tough thing to do an exhibition about.

An exhibition about war gets to show off some nifty halberds. One on the Queen’s fashion can display fluorescent dresses made special by a light seasoning of royal skin cells.

An exhibition on news gets to exhibit… front pages.

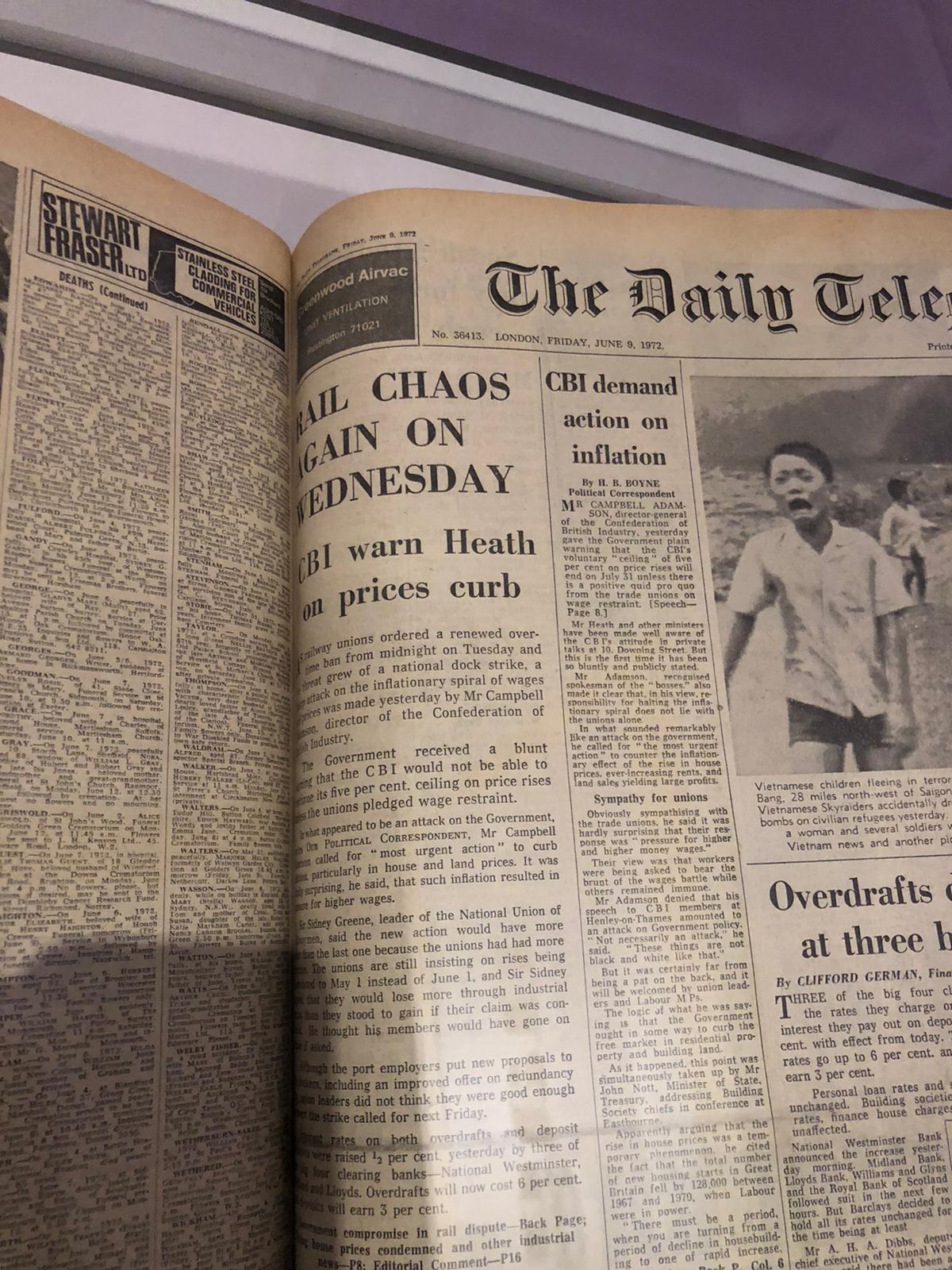

Its The Sun Wot Won It front page at the Breaking the News exhibition at the British Library. Picture: Press Gazette

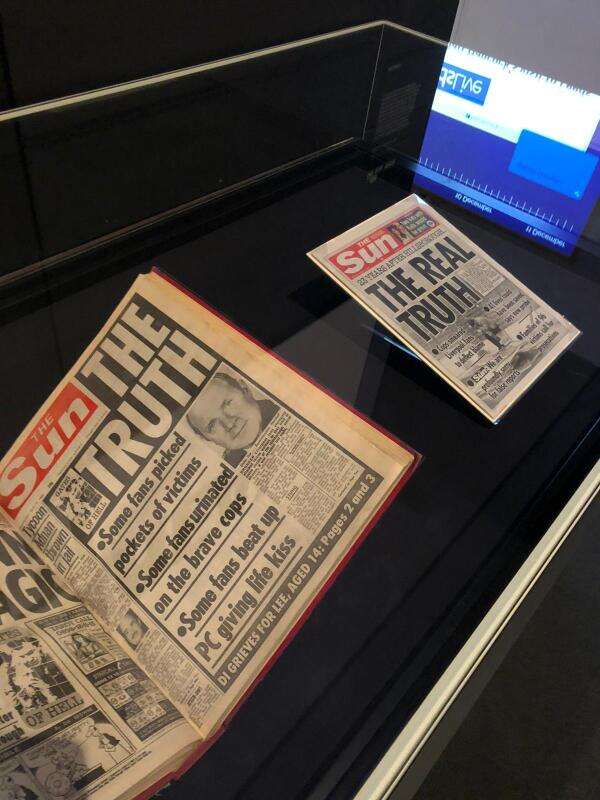

Sure, there’s a tang of history in the air when you linger over an original “It’s The Sun Wot Won It” spread. But it’s not the same as seeing in person an iconic prop or a noted murder weapon.

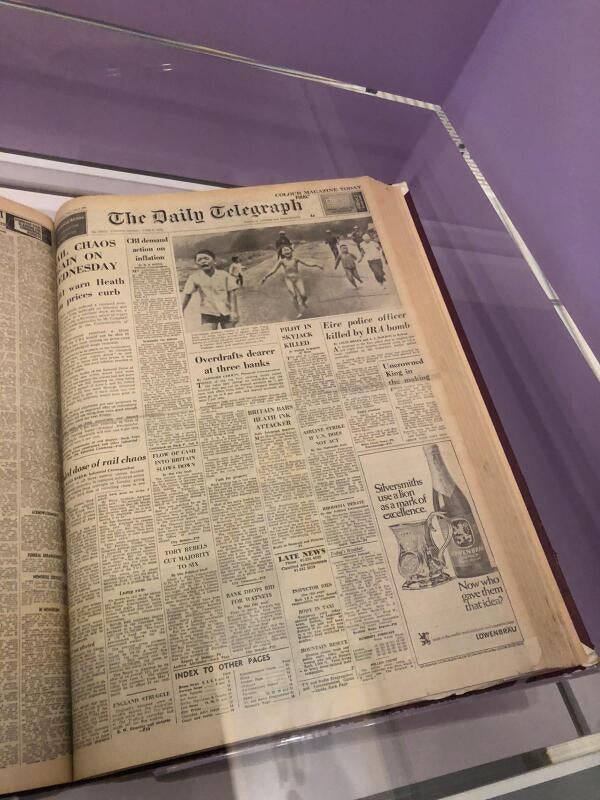

Media has awkward artefacts. Marie Colvin’s last broadcast from Homs and The Independent’s cover showing a refugee child drowned on a beach continue to punch their message home as clearly as they ever did.

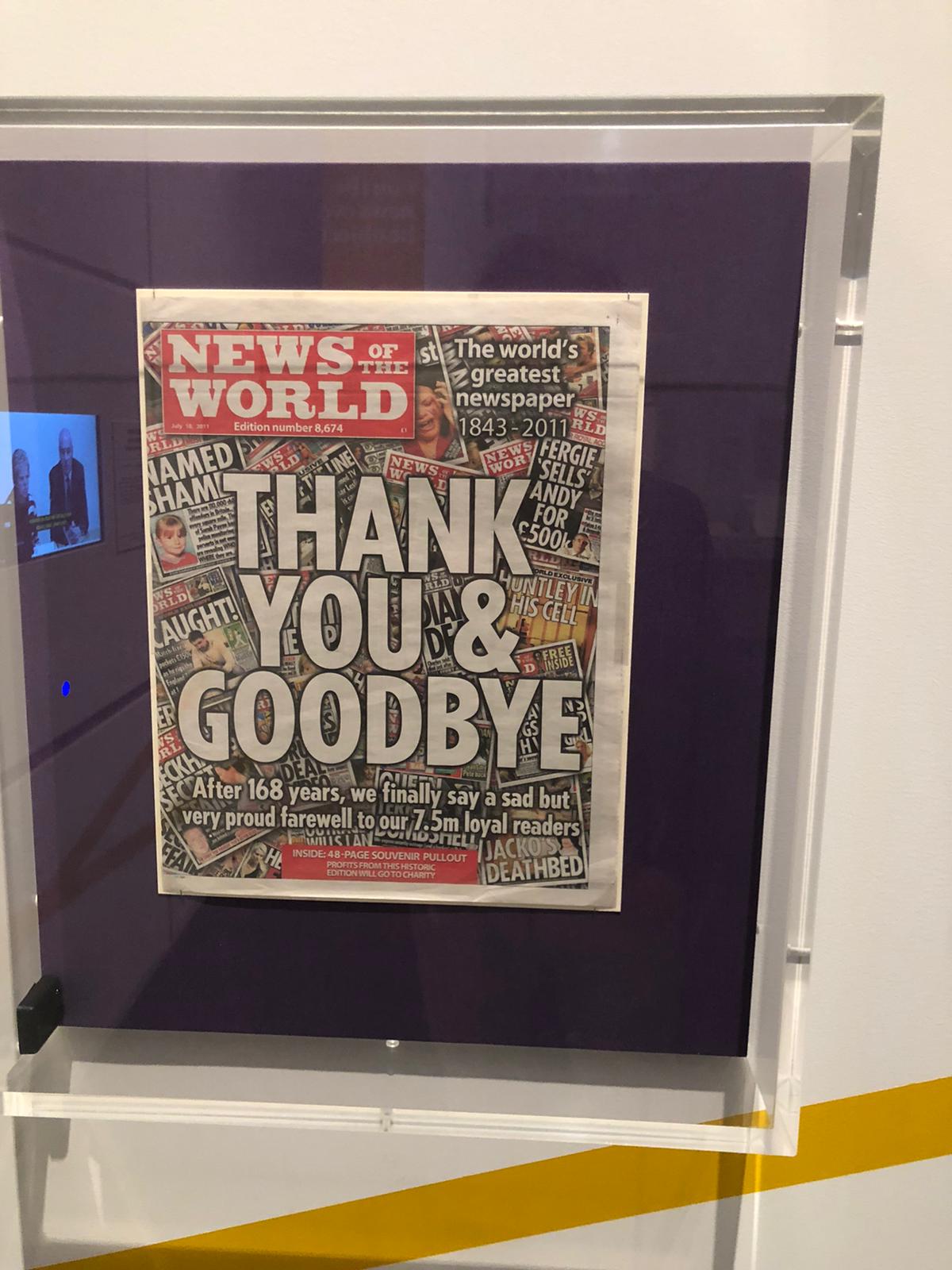

But the products of journalism are generally intangible or mass-produced. Their first concern is to convey information, so encountering “original” front pages up close, even those from before your birth, is not much different an experience than seeing them on a screen.

Syria and Marie Colvin at the Breaking the News exhibition at the British Library. Picture: Press Gazette

In that sense, the British Library and Newsworks’ new show is less an exhibition than a meditation. In a welcome and slightly surreal turn, the curation puts space between us and the ceaseless crush of news outside the walls.

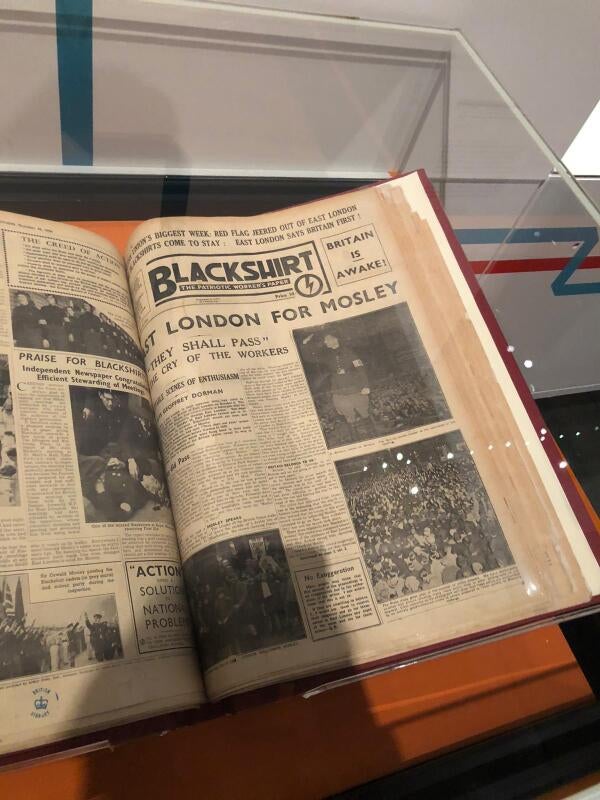

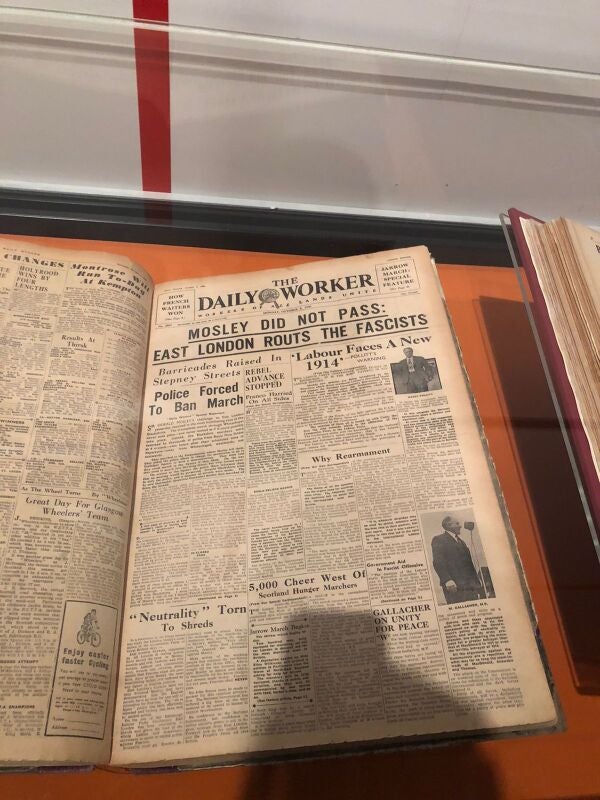

Visitors are presented with images from the fresh past as though they were from 1700: Brexit memes from 2017 and “Stay Alert” spreads from 2020 hang alongside wizened political pamphlets and leaked Byron poems.

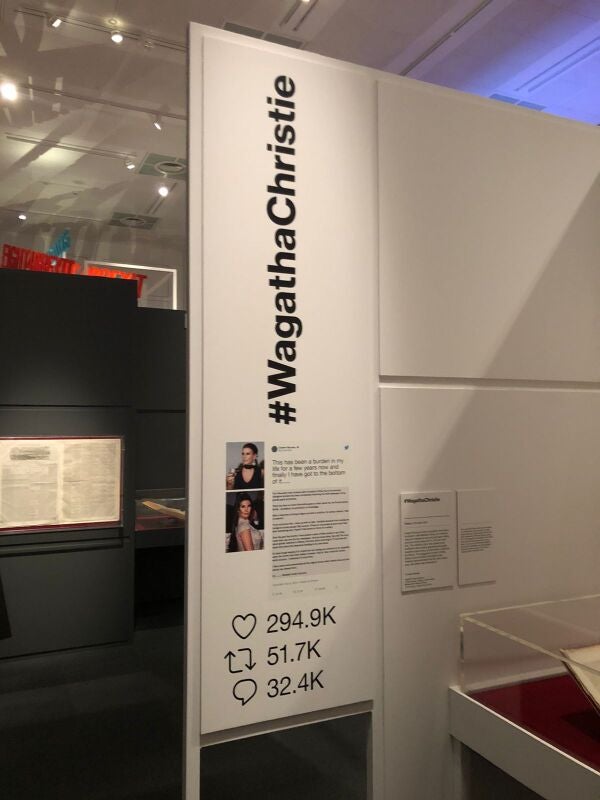

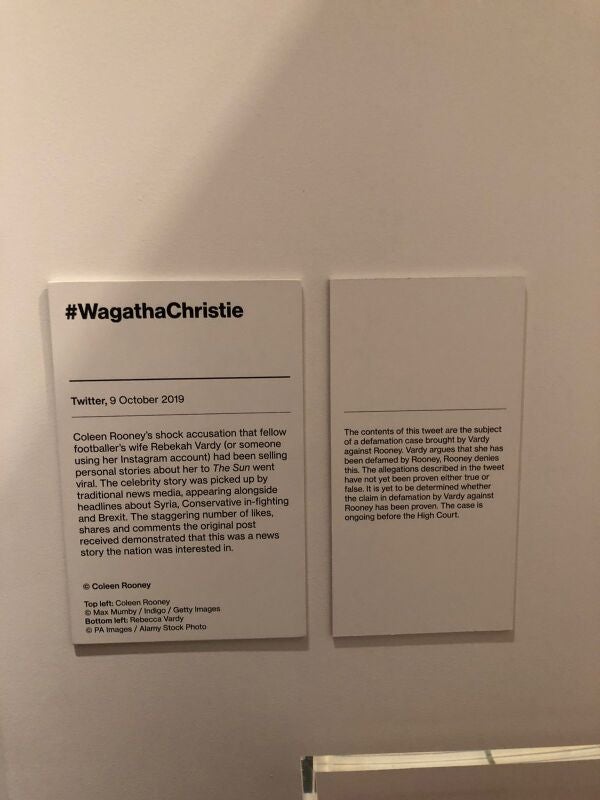

A rare acknowledgement that the stories aren’t all ancient history comes in a Wagatha Christie installation that has, unlike the others, two explanatory labels – one discussing the digital fracas, another (easily replaceable) one making clear that High Court proceedings are still active and Vardy’s guilt has not been proven.

Breaking the News promises to ask “big questions about the news we consume”, and news consumers are ultimately who the exhibition is targeted at. Some journalists might not be thrilled to have shelled out £16 to be told that power, celebrity and disaster are major themes in news coverage.

Guardian Snowden hard drive: Breaking the News exhibition at the British Library. Picture: Press Gazette

But there’s something for journalists there too. The deft weaving together of rhyming coverage from different centuries gives us a chance to think about what’s changed and what hasn’t between the reporting of Oscar Wilde’s incarceration and that of the expenses scandal.

And the exhibit features a valuably difficult installation on Grenfell, which asks why the media coverage that might have averted the disaster only arrived after the catastrophe unfolded.

If nothing else, this exhibition offers a digestible spin through the hits and pits of British media history. And, despite my earlier scepticism, the curators do manage the heroic job of collecting together some notable historical objects.

Breaking the News exhibition at the British Library. Picture: Press Gazette

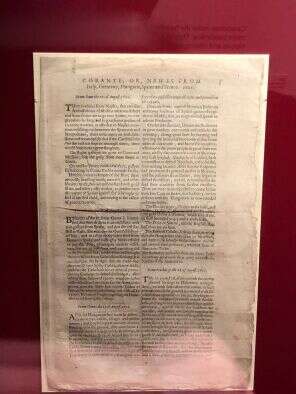

The scratched and shattered remains of the hard drive used by The Guardian to store Edward Snowden’s leaked NSA files are one notable highlight. The oldest surviving newspaper published in England is another.

“There is advice from Naples,” it records, banned by James I’s censorship laws from writing about English news, “that certaine Abassadours of Messina are arrived there and from thence are to go into Spaine, to congratulate the king and to give him a present of 150,000 crownes, as also that in Naples a contention falling out between the Spaniards and Neopolitans, there were many on both sides slaine and wounded so that if the Cardinall the Vice Roy had not slept in amongst them, there would have bene a great slaughter”.

To wit, second takeaway: lede writing has improved markedly since 1621.

‘Breaking the News’ is at the British Library until 22 August 2022. Tickets can be purchased here.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog