Croydon Advertiser reporter Gareth Davies writes about the impact of changes to the Met Police PR operation which have seen the force launch its own news website

In Babylon, Danny Boyle’s comedy-drama about the Metropolitan Police, director of communications and social media guru Liz Garvey tries to set up the Metwork, the force’s own “news division”.

“Who makes more content than we do?” she asks. “Who generates more news or more footage than the police? And what do we do with it? We give it away to news outlets who chew it up and spit out the facts and serve up their own slobbering mess to whoever is still listening.

“The Metwork – our own news division. We keep our content, we turn it into news and we put it out there ourselves. We shut out the press and go directly to the public.”

James Nesbitt’s fictional police Commissioner describes the idea as “state TV, the evening news from North Korea” but someone from the real Met must have been watching and nodding in agreement. The Metwork, it appears, has just been launched.

Last week Ed Stearns, the Met’s actual head of media, announced that, as of 1 May, the page usually used by the press – www.met.police.uk/pressbureau would be replaced with a new website. The site, which is not completely finished, can be viewed here.

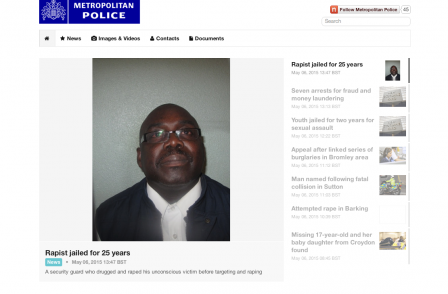

A bland but functional list of incidents and press releases has been replaced with, well, a list of incidents and press releases on a site that looks like it has been thrown together in a few minutes using one of the free templates on WordPress but has, in fact, been created by Mynewsdesk, a Swedish “PR platform” whose clients include L’Oreal.

It all looks very much like a local paper website from 2010 and perhaps that is the point. Aside from the more prominent use of pictures, video and social media there is one fundamental difference between the new website and the old one: it will be available to both the press and the public.

“We keep our content, we turn it into news and we put it out there ourselves. We shut out the press and go directly to the public” – Liz Garvey, Babylon.

New look and old look Met Police press websites:

Mr Stearns, in a “blog post” on the new site, says the “exciting” changes coupled with the “squeeze of budgets on police support staff” means the Met is “always looking at innovative and cost effective ways of getting information and content out to the media in a format they view and use with ease”. He says the changes are about improving the flow of information:

“Highlighting the release of our content such as images and video, it should also improve our distribution to journalists, and provide better integration with our social media accounts. We think it brings everything into one place in a user friendly way.”

His message to reporters concerned about this change in direction?

Journalists will still get some information by email, officers will still be put up for interview and the Press Bureau are still on hand to take calls from accredited journalists.

“However, we think the new website gives us more opportunities to provide relevant and timely content to both media and the public.

“It will take time to establish but we are hopeful that it will enhance the 24/7 news service already provided by the Met.”

"The Metwork – our own news division. It’s a news network like the BBC or CNN but exclusive to us” – Liz Garvey, Babylon.

The “news service” provided by the Met is primarily run by the Press Bureau, its central press office, which Stearns says handles 60,000 calls a year. Last week a Press Gazette FoI request revealed the Met employs more than 100 communication staff with an annual budget of more than £10 million.

“On top of that,” explains Stearns, “officers throughout London’s boroughs are encouraged to speak directly with the media about the issues they are dealing with and last year there were 675 face to face interviews with media organised by our media teams.”

The key part of that sentence is how it ends: “organised by our media teams”.

In my seven years as a reporter in Croydon the Met has never given the impression that it encourages officers to speak directly to the press. When it happens it is the exception rather than the rule, and it has become particularly infrequent following the breakdown in relations between the Met and the media in recent years. Most of the time an approach to a police officer will end in being directed to a press officer and, when you do get to speak to one, someone from the “media team” is invariably present, either to check what is being said or even provide their own opinion.

Perhaps this is all part of the “big step change” Stearns has identified in how information is “published and consumed” in the last three years.

“More than 200 officers around the Met are putting out hundreds of pieces of information and engaging in conversations every day via their Twitter feeds,” he explains.

In Croydon there has been a noticeable increase in police officers on Twitter posting about crime prevention as well as incidents they have attended, some of which would probably not have been publicised by the press office.

What happens when a journalist wants to know more about what happened? My experience has been less than encouraging. On 23 February, for example, a neighbourhood sergeant based in Croydon tweeted a picture of a large knife, explaining: “The team have charged a teenager for taking this knife into school. He awaits court appearance! #knifecrime #croydon”

What happens when a journalist wants to know more about what happened? My experience has been less than encouraging. On 23 February, for example, a neighbourhood sergeant based in Croydon tweeted a picture of a large knife, explaining: “The team have charged a teenager for taking this knife into school. He awaits court appearance! #knifecrime #croydon”

The message was posted at 8.10pm – several hours after local press officers go home for the day – so I sent the officer a direct message asking for some more details (where the knife was found, date/time, which school, etc) along with an assurance that I wouldn’t name the charged teenager due to his age. I am still awaiting a reply.

The next day I asked for the information the usual way. On 25 February I was told by a press officer that a 15-year-old boy had been arrested after staff confiscated the knife. The Met declined to identify the school or provide the name of the student, making it unnecessarily difficult to follow the case through court.

In many other stories our reporters have approached the Met press office and asked for basic information about incidents only to be told to go back to the officer who tweeted the information, and then failed to reply, in the first place. Even when we have received a response the stock answer from those officers has been to send us back to the press office. This is the Met that claims “officers throughout London’s boroughs are encouraged to speak directly to the media”.

The end result is that these incidents are either reported with basic information missing, lost within the court system or simply not written about at all.

The launch of the “Metwork” is not the only way the Met has recently changed the way it deals with journalists.

On 9 April reporters on local papers across London received an email to say that, as of 13 April, “all media enquiries have to go via Press Bureau”.

It might help at this stage to explain how the structure worked at the time. Press Bureau is the Met’s central press office. It operates 24/7 and is responsible for taking calls from accredited reporters and managing the website described earlier, providing the media with information about breaking incidents and convictions, publicising appeals and issuing statements about major issues.

As a local paper we go to Press Bureau for lines on significant or out-of-hours news. For all other incidents (for example: someone hit by a car, burglary at post office, non-fatal stabbing) we were expected to go to one of four press teams, made up of four or five media officers. Each team worked roughly 9am to 5pm and covered four “clusters” of London (individual boroughs used to have press officers of their own – Croydon had two as recently as 2008 – but these were cut and eventually replaced by teams covering larger areas in 2013). The team covering Croydon was known as South Area.

Your immediate response might be to wonder what all the fuss is about – given the budget cuts it has faced the Met should be reducing back office staff to concentrate resources on frontline policing. But the cluster teams are not being cut. They are instead working only on “good” news.

The statement explained: “The South Cluster team will no longer be responsible for any reactive media enquiries which includes the general inquiries into incidents which have taken place, RTC (road traffic collision), Twitter follow-ups etc….

“The South Cluster team will now encompass ‘pro-active’ good news releases only.

“We will still be in touch with the boroughs and continue to liaise with officers to find out what is going on, getting the good news stories and letting you know of up-coming [sic] court appearances and sentencing’s [sic].

“We will continue to send out press released of any proactive work we undertake.”

The Met has said the changes are part of a pilot in which all “reactive media calls” will be handled centrally, “in a bid to help us better manage the demand upon us”.

The result is that press officers who local reporters rely upon to provide accurate information about day-to-day police incidents will no longer answer those types of questions. Instead they will only tell us about things the Met sees as “good news” – a charge, a conviction, a press release about a “crackdown” on cycle theft.

Any other questions must now be directed to Press Bureau, an already overworked team who, in my experience at least, have never been thrilled (or particularly forthcoming) when asked about any incident below a murder or terrorist attack, and who once told me to call back when I dared to ask, during a weekend World Cup match, about a breaking incident in which police had come under attack with bricks and fire extinguishers at an illegal rave attended by thousands of people.

We have been working under the new system for coming up to a month and my initial concerns with how it would work and what it would mean appear well founded.

During the last four weeks the Advertiser, like any local paper, has been alerted by readers to a number of emergency incidents – either by phone, email or on social media – including a large fire at a hostel and a child being hit by a car.

Previously we would have asked South Area press officers for information and, most of the time, they would have been able to provide it. However, on half a dozen occasions since the new structure was put in place Press Bureau has been unable to locate even the most basic of details and, even where they have, the information has either been incomplete, provided days after the incident has occurred or simply read off a computer screen, instead of being provided in a written statement (It is a small point but this has legal implications given the qualified privilege written statements provide).

On one occasion a reporter witnessed three police vans form a cordon outside a house for the best part of an afternoon only to be told no information could be found. Several times the problem appears to have been a, perhaps understandable, lack of local knowledge on the part of the press officer. At least one of the South Area team had worked in Croydon for a number of years. He knew the area and many of the officers.

Perhaps these are the teething problems of a new system rather than a concerted effort to manage, either directly or indirectly, the news agenda. But the outcome is that incidents are either reported with basic information missing or simply not written about at all. This is not about reporters having less to write about, nor is it about ‘hits’. These are matters of genuine public interest going unreported and the distortion of what is really happening on London’s streets.

Maybe Stearns and his bosses have realised that if you make it more difficult for journalists to verify and obtain information then they produce less “bad” news. The less crime they cover the more people use the Met’s now public-facing news service, either on its new website or on Twitter and Facebook, which are in turn fuelled by teams of press officers tasked only with pumping out “good” PR.

The Met might do well to take a leaf out of Danny Boyle's book after all.

Asked by Babylon’s answer to Bernard Hogan-Howe whether ‘Metwork’ would be like “Kim Jong-un doing a piece on funny pets”, Liz Garvey replies: “There is only one rule – we get it wrong, we air it. We get it right, we air it. This is how we rebuild the trust.”

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog