Mail Online managed a 690 per cent increase in audience in the first five years since its relaunch – from 18.7m visitors a month in May 2008 to 128m in May 2013.

It makes it the industry’s biggest current success story and it’s still growing incredibly quickly, with latest figures showing monthly 'unique browsers' worldwide approaching 190m – according to ABC.

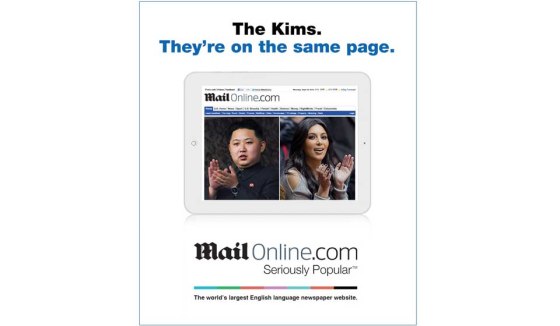

According to digital analytics company Comscore, Mail Online holds top spot in the UK not just for news but also for the celebrity-based categories of showbusiness, television, fashion and beauty.

The ‘sidebar of shame’, described as "journalism crack" by Mail Online publisher Martin Clarke, and the sheer volume of content – averaging between 500 and 600 stories a day – pulls and then keeps audience. Dwell time is said to be over six minutes per unique user, in an industry where two minutes is considered a pretty good show.

Maximising the potential of celebrity and journalism in the network has enabled Mail Online to use celebrity content with far greater focus than ever before.

The executive summary of Brand42 – the digital agency commissioned with re-launching the site in 2007 – describes how the site uses Web 2:0 techniques and an enhanced user experience to support an increase in volumes of content in an attempt to attract “a younger web savvy audience”.

This had a significant impact on the working practices of journalists.

Most significantly in terms of my own research, it reframes the significance of the interview. Interviewing is the traditional life blood of journalism.

Jeremy Tunstall in his study ‘Journalists at Work’ – found more than half of newsgathering time was spent interviewing people; 25 per cent of the time on face-to-face and 39 per cent on the telephone.

Thinking back to my own time in industry, this feels about right. I remember my first news editor telling me to never to leave an interview until I got ‘every cough and spit’. Later, working at Sunday newspapers, interviews with big buy-ups could last several hours. I’d sometimes conduct revisit interviews over subsequent days after a certain line had perked the editor’s interest at conference.

But celebrity content on Mail Online relies very little on direct interaction with sources. Much of it is no more than repackaging. This can include frame-by-frame accounts of the music videos of singers like Katy Perry, a scene from a reality TV show such as The Only Was is Essex or the interaction with fans on social media sites, particularly Twitter.

These are then repackaged, using templates which draw on traditional conventions associated with written journalistic production, such as the inverted pyramid structure and the linguistic devices for direct speech.

Amongst the most popular sources for Mail Online are the stars of a new genre of constructed reality television which emerged around the same time Mail Online launched. The stars of early examples of these shows such as MTV’s The Hills, ITV2′s The Only Way is Essex or E!’s Keeping up with the Kardashians are now examples of networked celebrity as brands. Selling product seems to be the key purpose of the shows in the first place.

To look at the levels of content about the stars of just one of these shows – The US Kardashian family – shows the vast influence they now have on the Mail Online news agenda. In my five-year study timeframe, Mail Online published just under 4,000 stories about the family of which around 30 per cent were directly sourced from their tweets.

Those producing this content don’t directly source their own material through interviews and contacts and think about the best way to use it, but instead aggregate content and place it into a pre-created “highly optimised” template.

This poses a significant question: are the people working on this kind of content for Mail Online journalists?

Such Mail Online workers are certainly not journalists of a kind that Tunstall would have recognised. Instead they represent a new kind of media worker. We might term them digital content processors who use the work of others, in this case the performances of celebrity and their interactions with their audience, to generate news lines for them and then repackage it in a way which will optimise audience.

These digital content processors clearly work alongside journalists operating in a more traditional way. Lead stories on Mail Online are usually the ones that have made the paper and many appear to be produced by journalists using sources and interviewing. But a number of distinctions can be seen when comparing to the practices of traditional journalists.

They place speed over accuracy, with stories up quickly and then amended or corrected later. This process is recorded under the byline at the top of each post, which highlights updates. Quantity is valued over quality, with multiple lowbrow and low researched stories produced in a day.

These workers are also not traditional news gatherers, but news aggregators, pulling together online content – in this case the networked performance of the celebrity as brands – to produce stories given the appearance of news. As such they can churn out prolific amounts very cheaply, which keeps pulling audience to the site.

The importance of cost comes into clear focus when you examine the revenue and profit – or lack thereof – of Mail Online itself. Despite attracting huge audiences through cheaply-produced celebrity-focused content it still isn’t making much money.

The indications that revenue will follow audience are improving, with parent company Daily Mail and General Trust announcing growth in digital revenue is now offsetting print decline and that the site broke even for the first time in 2012. The site also achieved a 41 per cent increase year-on-year in revenue to £41m by September last year, but this compares with total turnover for the Daily Mail and Mail on Sunday titles in print and online of £603m.

The quest for advertising revenues has resulted in Mail Online finding another use for this celebrity content. Once it has captured audience, it now tries to sell product directly to them.

A story constructed around a celebrity’s tweet about a new make-up line or a paparazzi picture of them going to the gym, often now offers the reader the opportunity to buy the clothes they wear. This has led to Mail Online setting up its own ‘Fashion Store’, built entirely around coverage of celebrity.

It looks like advertorial in news’s clothing. Which makes the term digital content processor an even more compelling job descriptor for those producing it.

This research is part of a wider examination into the changing significance of the journalistic interview, particularly to the formulation of celebrity culture. Bethany Usher’s study into the performance of David Bowie in interviews is published in David Bowie: Critical Issues by Routledge later this year.

Bethany Usher is a former journalist for the News of the World and now a principal lecturer in journalism at Teesside University.

Follow @bethanyusher.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog