The Labour Party set out its legislative agenda in the King’s Speech this week. Through this it has softened its commitments to introduce legislation to regulate AI. This does not augur well for a rapid resolution to the AI/IP problem.

This King’s Speech was never expected to hold much for the news sector. The long-running legislative changes that mattered most were passed through wash-up at the end of the last parliament.

In the last days of the Conservative administration we finally saw the passage of the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act. This will give force to a new regulatory regime – five years in the making – aimed at addressing competition issues in digital markets. And of course the repeal of Section 40, which could have required publishers to pay legal fees to complainants – regardless of the outcome of their complaint – unless they were signed up to a state-backed regulator.

But increasingly these feel like yesterday’s battles. With Google referrals dropping and search interdependence faltering, the frontline for publishers in their online operations is becoming AI.

Large language model chatbots have been trained on publisher archives, without authorisation or payment. In some instances they are being used by consumers instead of original content. If you’re looking for a travel itinerary or recipe inspiration, you’re going to get what you need faster by using AI instead of scouring multiple sites via search.

[Read more: Google AI Overviews breaks search giant’s grand bargain with publishers]

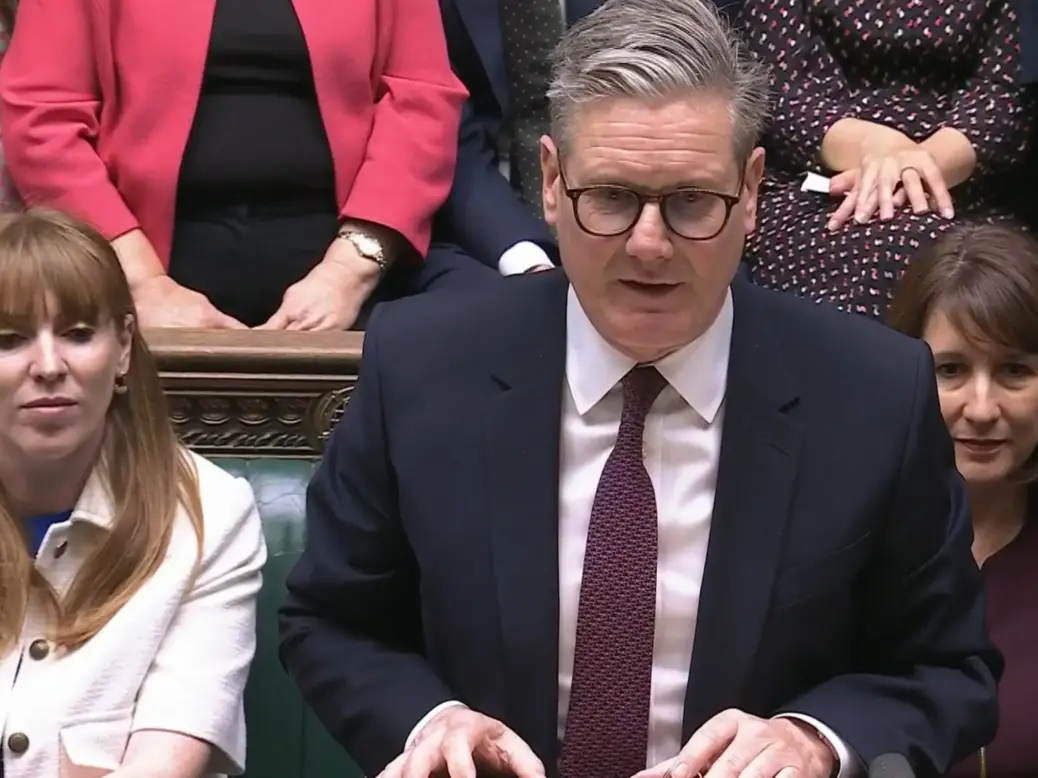

In the days prior to the King’s Speech it was trailed that we should be expecting a firm commitment to introduce an Artificial Intelligence Bill in the first year of the Starmer regime.

Ultimately this was weakened, with instead the King telling us that his government would “seek to establish the appropriate legislation” to regulate “the most powerful artificial intelligence models”.

Whilst perhaps tonally a slight advance of the previous administration’s, this suggests both a delay and a focus on the end-of-the-world harms (which has been a useful and effective means by which AI firms have distracting lawmakers), rather than the more prosaic issues surrounding copyright infringement.

Conservative government ‘made a mess’ of AI policy – what’s next?

The outgoing Conservative government made a mess of policy in this space. Back in summer 2022, out of nowhere, it announced the intention to create an extreme form of “text and data mining” copyright exception. This would have given free rein to anyone wanting to ingest copyright materials to, for example, train a large language model. This exception would have applied even if that model is being used commercially.

Outcry from the creative sectors followed. This was amplified when, a few months later, OpenAI released ChatGPT 3 which, it was clear, had been trained on a corpus of data including vast amounts of copyright materials.

Ultimately the government scrapped the exception in early 2023 and instead tasked the Intellectual Property Office with establishing a working group to try and resolve the issue through the creation of a voluntary “code of practice”. After months of predictably-fruitless work, this was also abandoned, with participants failing to agree on the most basic points (i.e. is a licence required for AI model training).

From that point until the government limped out of office, its policy was seemingly “masterly inactivity”. Court cases had started to be filed on both sides of the Atlantic and rather than weigh in to support rights-holders, instead it sat back and let the judicial system do its thing.

[Who’s suing AI and who’s signing: Publisher deals vs lawsuits with generative AI companies]

Rumours abound that ministers and officials were subject to intense lobbying from tech firms. Any use of the word “licensing” was subject to fierce opposition. Decisions about where to deploy AI investment were a powerful bargaining chip for those working under a pro-tech Prime Minister Sunak (note Labour’s manifesto also describes an industrial strategy which “supports the development of the Artificial Intelligence (AI) sector”).

But the court cases will take many years to play out as technical arguments surrounding the precise processes involved in training a LLM are scrutinised. The consensus in the UK is that the existing legal framework will, ultimately, offer the protections that rights-holders need. However much harm may be done in the interim.

Whilst an AI Bill may not have been the right vehicle to provide clarity on the application of IP law to AI, it would be a good means of ensuring transparency around training data and signalling the Government’s position on this issue.

The EU’s AI Act includes such a provision but the wording leaves substantial wriggle room for big tech (requiring only “sufficiently detailed summaries” of training data to be published). The UK could have set the global standard in this narrow space.

Clearly it is early days for the Labour administration. There are reasons to believe that its instincts are likely to be more supportive of rights-holders and the UK’s creative sector than the previous government. But giving rights-holders the control over the use of their IP, and confidence in the application of IP law, is urgently needed.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog