Ask most journalists about the Defence Advisory notice system, and – even if they have heard of it – they would probably have only a hazy idea of what it does.

But after the Press Complaints Commission and Ofcom, it’s the only other body in the UK which regulates what news organisations can and can’t report.

It is a peculiarly British arrangement. The media does not have to obey the code; it is completely voluntary. But it is rare for any news organisation to ignore DA-notices, because a voluntary code which works is usually preferable to a compulsory one.

The system broadly covers any stories that affect national security. There are five standing DA-notices, covering military operations, weapons, codes and communications, sensitive installations and intelligence operations. In fact, the sort of subjects which usually make good stories.

DA-notices are why the media does not, or at any rate should not, identify British intelligence agents, or show photos of secret military bunkers, or give details of the techniques used by Special Forces.

The system has existed in one shape or form since 1912. Originally its existence was more or less secret. D-notices, as they were called until 1993, could be slapped on stories to prevent their publication and the public would know nothing about it.

It was sometimes the stuff of sensation and controversy.

Since the system became voluntary, as far as the media is concerned in 1993, it has become much harder for governments to use it to stop stories without good reason.

Today, the DA-notice system is overseen by the Defence, Press and Broadcasting Advisory Committee, made up of the ‘official side'(from the Home Office, MoD, Foreign Office and Cabinet Office) and media representatives from news organisations. Regional papers are represented by the Newspaper Society.

The committee is always chaired by the Permanent Under-Secretary for Defence; the vice-chair always comes from the media side.

The idea is that a journalist doing a story which is covered by one of the five standing DA-notices should first check to see if it is covered; and, if unsure, should take advice from the committee secretary.

Some people, mainly from civil liberty groups, have been critical of the system in the past – accusing it of indulging in cosy, self-censorship.

But the media members of the current committee are no pussycats and demand firm evidence that national security is threatened before agreeing to government requests.

(You can read the minutes of the committee’s meetings on the DA-notice website: www.dnotice.org.uk/ )

The current secretary, Air Vice-Marshal Andrew Vallance (whose contact details are also on the website) takes an independent line, sometimes to the chagrin of the MoD.

The system and the committee are probably more relevant today than for many years. With UK Special Forces active in Iraq and Afghanistan, and British Intelligence pitched against terrorists at home and abroad, there are plenty of stories, programmes and books to keep the secretary busy.

The growth of the internet has added a new dimension to the arguments about the system. There is plenty of content on the web which breaches DA-notices, though generally not on mainstream UK sites.

It creates a challenge to the concept of the ‘public domain’which is one of the main planks of the system.

Why should a British newspaper not report something if it’s all over the net? There may be no clear answer to this, but at least it’s being discussed.

The DA-notice may not be perfect, but it has to be better than straightforward government censorship, and probably the best we can do in a 21st-century democracy.

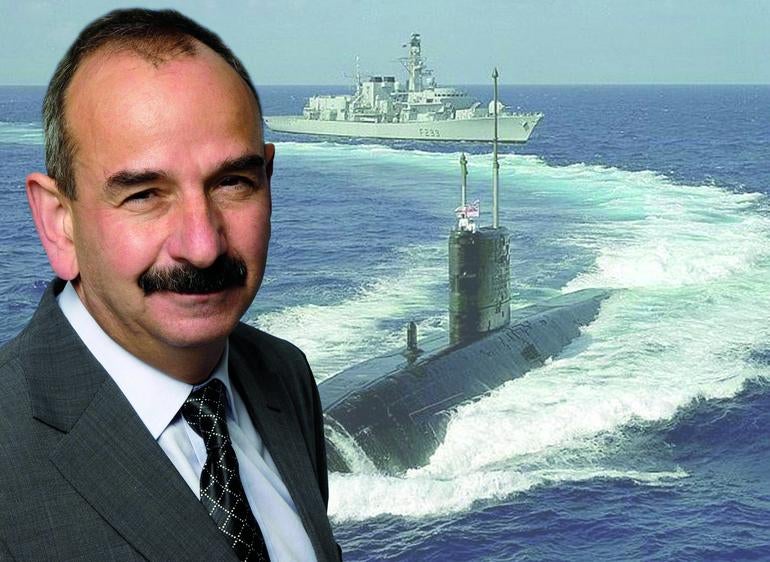

Simon Bucks is associate editor Sky News Online and vice-chairman of the Defence, Press and Broadcasting Advisory Committee. He is the first broadcaster to hold this position

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog