Leslie Parkin, who has died aged 98, came from a newspaper world long gone, where a city evening paper could sell hundreds of thousands of copies and bring out five editions a day.

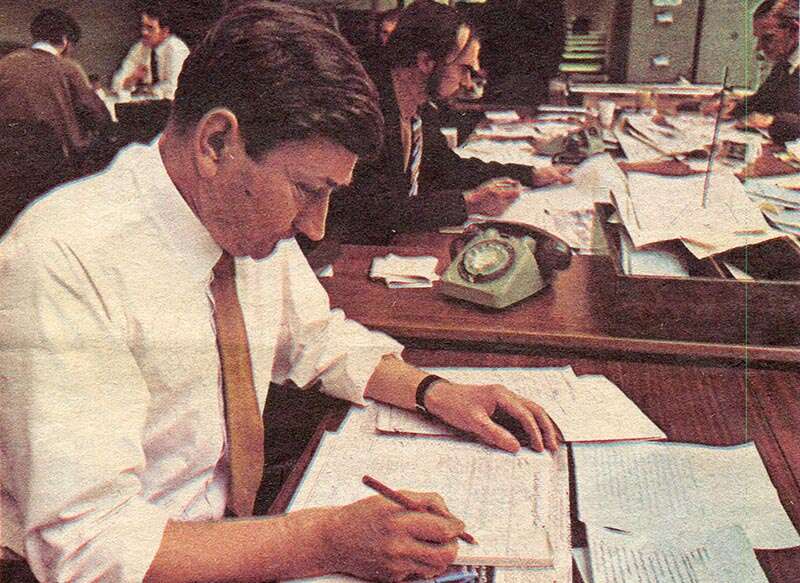

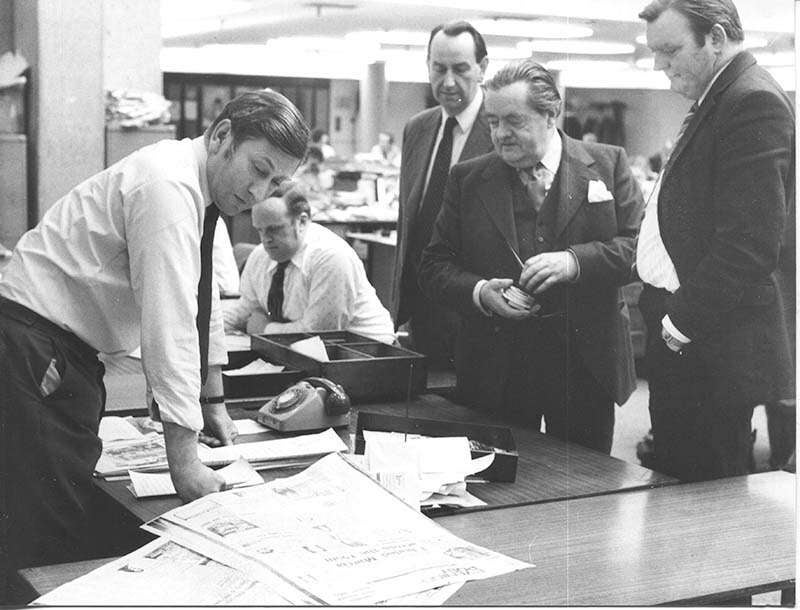

It was a world of fast page changes and fast decisions. In it a layout man with a pencil and a paper pad in front of him could draw up his front page and hardly have time to tuck his pencil behind his ear before re-doing the whole thing for the next edition.

Les, as chief sub and later chief assistant editor of the Yorkshire Evening Post, enjoyed every one of those decisions. He once moved the masthead of the paper to run it down the side of the front page to make room for a particularly important story. His headlines were brief and tuned in to the readership. The Yorkshire ripper was committed for trial with the terse words ‘It’s the Old Bailey’. Everyone in the county knew what that meant.

When Katharine Worsley, of Hovingham, York, married Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, in the first royal wedding at York Minster for over 600 years, she walked out under its famous rose window as the Duchess of Kent. Les’s headline was simply Rose of York.

It took a particular personality to thrive in newspaper conditions then. It was not for faint-hearts. Competition in Leeds, with two evening papers, was tough. When a promised pay rise on the Yorkshire Evening News, based in Trinity Street, didn’t materialise, Les famously walked out of the paper with the day’s splash in his top pocket. Messengers were sent to the pub by a desperate editor, but by then Les had something else in his top pocket as well – an instant job offer from the rival paper, the Yorkshire Evening Post. Up the hill to Albion Street he went that day, and he didn’t give the copy back.

Les started young, while still a boy in Dewsbury, where his father was a butcher and Methodist lay preacher. Fascinated by geography and maps, he wrote a piece in 1939 at the age of 14 on the strategic importance of the Shetland Isles and Ireland. The editor of the Shetland News in Lerwick published it and asked for more. One of his letters to the young Leslie in 1941 thanked him for an article on Yugoslavia, enclosed stamps for him to send his handwritten copy and offered to send more paper if he needed it.

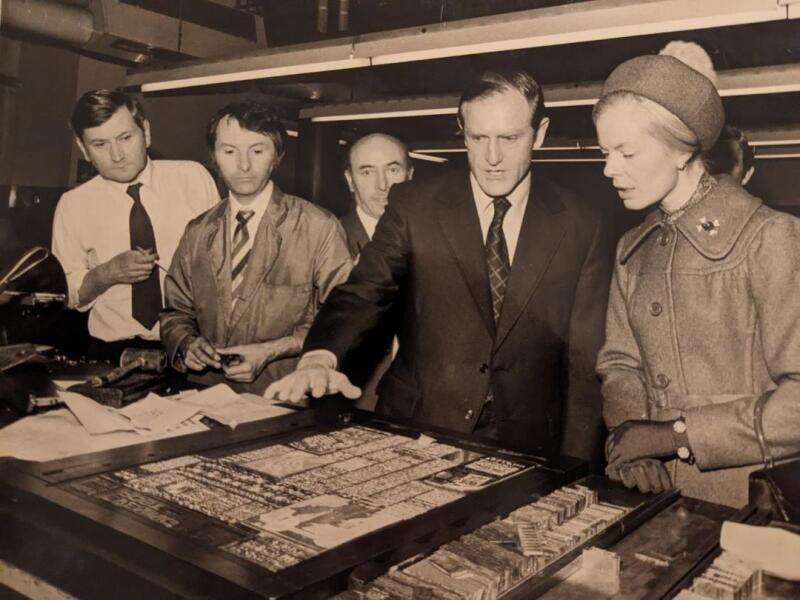

Leslie’s family couldn’t afford to pay for an indentured apprenticeship on a local paper, so he did it the hard way. His training on the Batley News included almost every possible job – cycling round reading local notice boards for ‘pars’, stoking the boiler, sweeping the printroom floor and tidying the hot metal trays. It was that which led to his career-long rapport with the powerful and notoriously militant printers of the day.

Stayed in Yorkshire

Les, able to read the pages back-to-front in the printroom, understanding both hot metal and its successors, was one of the few journalists of the time popular with the printers, who didn’t like haughty newsroom types. If a compositor spotted a mistake, he’d phone up to Les, knowing he’d be thanked, not spurned. ‘In newspapers, you need all the friendly pairs of eyes you can get,’ said Les.

Having started on the Batley News days before his fourteenth birthday, he was made redundant only weeks later, because of the outbreak of war. He took a job as a railway booking clerk. ‘Not many people have been made redundant at 14,’ he used to say.

The panic was brief and within weeks the paper, short of manpower because of the call-up, took him back to slightly higher things, including covering the magistrates’ court in Birstall, then held in a room over the bar in the Black Bull pub. By then he’d learned an arcane form of shorthand, called Dutton’s.

After wartime service in the Royal Navy, Les returned to papers, in Leeds and Manchester, then home of the northern offices of many national papers, including the old News Chronicle. London job offers followed, but by then Leslie and his sweetheart and fellow ex-Batley News journalist, Eileen, had married and started a family. He stayed in Yorkshire, subbing on the Yorkshire Post for six years before that stint on the Yorkshire Evening News, and eventually settling on the Yorkshire Evening Post, until his retirement in 1990.

In those days, the office was on the corner of Albion Street, a newsroom full of men, ashtrays, shirtsleeves and those terrible spikes for dead copy. In the sixties, the YEP saw off its smaller competitor, the YEN, and its circulation hit its peak of 320,000 copies a day.

The paper moved to swish new premises on Wellington Street, opened by the then Prince of Wales in 1970. It may have been ugly to many eyes, but luxurious to those who’d know the Albion Street building. Les still had the commemorative mug when he died on Good Friday last month.

All buildings have their stories, of course, but newspaper offices have everyone’s stories. They came into that huge newsroom from Reuters, Press Association and the rest of the agencies worldwide in paper streams, which spewed out in the wire-room. In there, the men were used to Les coming in from the subs’ table to find out what the latest rushes were, instead of waiting for them to come to him. His training in the Royal Navy signals meant he was at home with those mysterious tap-taps on the wires.

Stories came in over phones, in letters and from the pub. They came in from reporters for whom new technology was turning your notebook over to use it again, backwards, who rang in from phone-boxes, praying they could get a copytaker before the deadline, that they could ‘catch the edition’.

Police corruption, Poulson and Kagan, the miners’ strike, Revie and Bremner, Lockerbie, Peter Sutcliffe, the Falklands War, Dewsbury going Tory, Piper Alpha, York Minster aflame, Hillsborough and Valley Parade, heroes and heroines, villainy and venality: all the stuff of human life. Deadlines, splashes, editions – they were Les’s world and he loved it. In retirement, he described his career in one word – fun.

Leslie Parkin (1925-2024) is survived by his wife, Eileen; his daughters, Janet and Jill; his grandchildren, Rosie, Jack and Beth; and a great-grandson, Charlie.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog