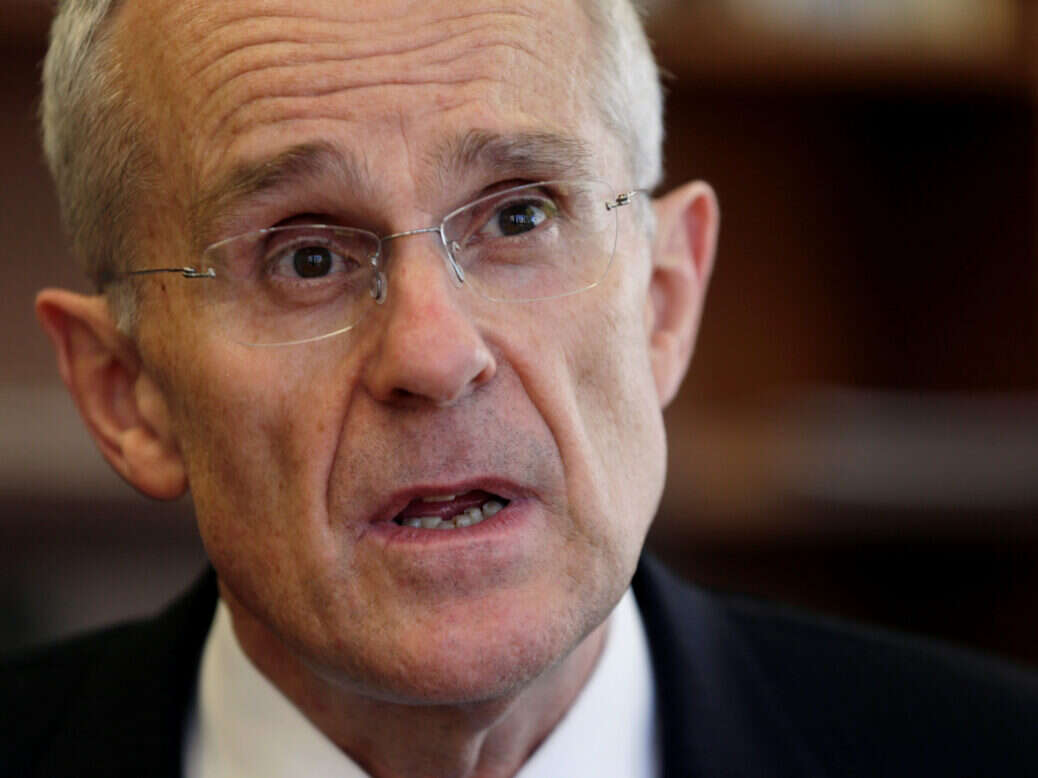

One year after Australia’s parliament passed legislation that forced Google and Facebook to start paying for news, Press Gazette spoke to Rod Sims – the man who made it happen.

He is the chief architect of legislation that he estimates has resulted in content licensing deals worth more than AU$200m (£106m/$145m) for the Australian media.

And the code’s impact doesn’t stop there.

The governments of Canada and the UK are both aiming to introduce Australia-style legislation in the coming months. In the US, news publishers are lobbying hard for similar rules of their own.

If Australia’s legislation is rolled out in some form across these countries and others, then it could have a huge financial impact on big tech and the global journalism industry.

“Oh, yeah. It’s a big deal” says Sims, who is due to leave his post as chair of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) in March after 11 years.

“Look, it is,” he adds, in a 30-minute video interview ahead of the code’s one-year anniversary. “I’d just say that these are huge companies. Their revenues are just enormous. Their profits are enormous.

“And, of course, they make money out of providing content that people want to watch, and then they advertise to people that watch that content.

“So I don’t think it’s unreasonable that you pay a significant amount for the content from which you make an enormous amount of money.”

Click here to subscribe to Press Gazette’s must-read newsletters, Future of Media and Future of Media US |

Australia’s News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code was the product of several consultations and reports, most of which were managed by the ACCC under the guidance of Sims.

The code was designed to force Google and Meta (formerly known as Facebook) to start paying licensing fees to news publishers. It also gave publishers the opportunity to collectively negotiate deals with the companies.

The journalism industry in Australia and beyond had long argued that Google and Facebook benefit from news content – which attracts traffic and ad revenue – and should therefore contribute to the cost of producing it.

Publishers also argued (and continue to argue outside Australia) that Google and Meta’s duopolistic hold over the digital advertising market means they could not fairly negotiate with them. Between them the pair take more than $200bn a year out of the global advertising market.

The code effectively states that if “designated” digital platforms cannot agree cash-for-content deals with publishers, then the parties should enter an arbitration process.

However, neither Google nor Facebook/Meta was named in the legislation. Nor has the Australian government “designated” either of them as digital platforms for the purpose of the code. This means that, technically, neither currently face the risk of arbitration through the code.

Yet, the threat of “designation” in itself has been enough to persuade them to strike several deals worth more than AU$200m a year, according to Sims.

“What happened is that the treasurer said to them, ‘Well, look, if you’re going to go and do deals then you may not be designated.’ So the threat of arbitration became the threat of designation. So you just replace one threat with another.

“So it doesn’t actually matter a row of beans from our point of view. The whole point was to up the bargaining power. That’s been done. All the media companies have got a deal post-the code going through, and I think all are happy with that deal. So the designation is no more important than the arbitration.”

Sims adds: “All we did was provide a mechanism that gave the companies much more bargaining strength. Because, had they been designated, we could have gone to arbitration.

“So we never wanted arbitration to be used. It could have been. It was more the threat of arbitration.

“So, just imagine you’re talking to a monopoly. What notice are they going to take of you? Well, none. But if you’re talking to a monopoly and you can take them to arbitration to get a fair deal, then they’re going to talk to you seriously. So the threat of arbitration is what it was about.”

Meta is ‘running a severe risk of getting designated’

One year on from the code’s introduction in Australia, Sims says it has “achieved almost 100% of what we hoped it would achieve”. But, he adds, “there are a few little issues”.

Namely, Sims is unhappy that Meta has refused to do deals with the Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) and The Conversation.

“If you had said to me, they’ll do a deal with everyone, but not SBS and the Conversation, I’d have said: ‘How do you call that?’ I mean, they’re the two most obvious candidates. So we need to understand that…

“They’ve done a deal with pretty much everybody, except they’ve missed out one mid-tier and one significant smaller player. I mean, go figure.”

Sims says there are a few other small Australian publishers that have been registered with the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) but have not been able to strike deals. “So we’ll have to look at that. But they’re extremely small.

“If you look at it from Google’s point of view, having done deals with SBS and the Conversation, I think you’d have to say virtually all journalists in Australia are working for companies that have got a deal from Google.”

Australia’s treasury is due to conduct a review of the code, one year on, next month. Sims predicts that Meta’s non-deals with SBS and the Conversation will be a major issue for the review to consider.

Could Meta be designated by the treasury and thereby face the direct threat of arbitration?

“I think the Facebook designation must come up, given they’ve not done a deal with two blindingly obvious – two companies you’d have thought were obvious candidates, and yet Facebook’s not done deals.

“So I think they are running a severe risk of getting designated. But it’s a decision down the track.”

Theoretically, other tech companies could in the future face the threat of designation and arbitration in Australia under the code. Is this a realistic possibility? Could it happen in, say, ten years’ time?

“A lot of media companies already have deals with Apple for Apple News, so we hadn’t felt the need that there was an imbalance there,” says Sims. “It just depends on the extent of the imbalance at that time, in ten years’ time.

“There’s got to be a significant imbalance in bargaining power. It’s not got to be: ‘Well, I didn’t get everything I wanted.’ No, no.

“With Facebook and Google – I mean, they didn’t want to talk to the media companies. So this wasn’t an imbalance. This was: ‘No.’

“So it just depends on the circumstances. Yes, it’s open to anyone to get designated provided there’s a significant imbalance.”

Do Google and Meta have a payment formula?

How does Sims calculate his estimate for total Meta and Google content deals in Australia?

“Different CEOs have given me different levels of information,” he says. “And just sort of triangulating it and it looking at it all, I’m confident it’s greater than AU$200m. But unfortunately, I can’t give chapter and verse.

“People ask me my best view, and that’s my best view – that it’s worth over AU$200m. I’m pretty confident that’s right. It’s an estimate, but it’s an estimate that I’ve got a high degree of confidence in.”

How do Google and Meta decide how much they should pay publishers? Do they have a formula?

“They would say, correctly, that it’s based on how much news and benefit Facebook and Google get – how much they rely on it,” says Sims.

“What I would say is that, from my experience, the amount companies were paid was extremely strongly correlated with the number of journalists they employ.

“I’m not saying that was the criteria, but you could just see. Who employs the most journalists in Australia? It’s ABC, it’s Nine, it’s News Corp, it’s Seven. Probably in that order. I don’t know. I honestly don’t know. But the first three are the three biggest. Seven would certainly be fourth, but still big.”

Press Gazette has reported that the Canadian media, based on information obtained from Australia, expects Google to ultimately cover around 20% of newsroom costs and Meta 10%. Does Sims recognise these percentages?

“I can’t bring that back into my ‘over AU$200m’ estimate. Certainly, off the top of my head, I can’t. There’s nothing wrong with those estimates. If they were talking about one or two per cent, I’d say, well, that’s silly. If they were saying 50%, I’d say, well, hang on, how are you going to justify that? So they’re not unreasonable numbers.”

‘They were employing just about every lobbyist in Canberra’

Ahead of the introduction of Australia’s code, Google and Meta made a series of threats against the country. Google said it might remove its search engine from Australia, while Meta briefly barred news from Facebook in Australia. Should other countries expect the same response?

“I always expected –almost because of the principle involved and the size of the money – that there would be massive threats around all this,” says Sims. “There just sort of had to be. I mean, why would you roll over easily?

“Back to the idea of commercial negotiations, I mean I’ve been involved in them with people who get the offer from the other side, stand up and walk out and say ‘that’s ridiculous’. There are all sorts of things that go on in negotiations, so that’s what I expected would happen, and it did.

“I think it might well happen for the next two or three countries that do it, but then probably not.”

How many other countries will adopt legislation based on Sims’ code?

“I don’t know,” he says. “Google and Facebook will lobby very hard. They are very powerful and they do employ a lot of lobbyists. They were employing just about every lobbyist in Canberra when this was going on. So, look, don’t underestimate their ability – their political influence.”

There are some signs of how Google, in particular, might respond to any laws that seek to replicate the Australian code.

Last week, in response to a Press Gazette story on the proposed Canadian laws, a Google spokesperson said: “We are committed to… collaborating with the government to create a ‘Canada made’ solution that will ensure a robust future for news in Canada and enable innovation. The Australian approach doesn’t do that and it doesn’t provide a sustainable model for the future of journalism.”

Sims says: “Google simply do not want the Australian model.”

‘That trigger is just sitting there waiting to be pulled’

Even beyond Google and Meta, the Australian code has its critics.

Nieman Lab’s Joshua Benton has described it as a “warped system that rewards the wrong things and lies about where the real value in news lies”.

Hal Crawford, a Sydney-based media analyst and consultant, wrote on Press Gazette that the code sets a “terrible global precedent because it is based on misrepresentation and delusion”.

Several media academics have suggested it might ultimately benefit large media companies at the expense of small, upstart would-be rivals.

Sims is alive to criticism of the code and challenges it often during this interview.

He says Google and Meta have done deals with many of Australia’s “smallest” publishers.

“They’ve done deals with Private Media, Swartz Media, the Saturday Paper, Country Press Australia, [an industry body that represents more than 100 local publishers]. A whole lot.” (The ACCC keeps a list.)

“I jump on this because some people say it’s only the big companies that have got deals. Well, that’s factually false. It’s not true.”

Sims adds that he believes “some of the smaller players” are being paid “a little bit more per journalist than the bigger players”.

A year ago, the Australian government also faced criticism from Lord Rothermere, the chairman of Daily Mail Australia owner DMGT, after it emerged that ministers had made certain concessions to Google and Meta in the code. He accused the government of having “surrendered” to threats.

Sims says: “There were a lot of assertions in the negotiations that the treasurer had with the chief executives of Facebook and Alphabet that a lot of concessions had been made, which watered the thing down.

“They didn’t. I was completely involved in all of that. They defined a few terms, they clarified things that they thought had read this way, we thought had read that way. For the avoidance of doubt, we redefined it. They were things that clearly haven’t altered the outcome.

“I just think that was an overreaction. In any negotiation, if you and I are negotiating, and something really matters to you and I don’t care about it and vice-versa, we give a bit of ground, and that was how I saw those negotiations.”

One apparent concession is that neither Google nor Meta have been designated by Australia’s treasurer.

“If you want to judge it a concession – that rather than arbitration being the threat, designation’s the threat – fine,” says Sims. “But I don’t regard it as a concession because the code achieved its objective. Whether the threat was designation or arbitration, doesn’t matter.

“That could well be a great example of something that mattered to Facebook and Google but didn’t really matter to us. We wanted the outcome. We weren’t after designation, we weren’t after arbitration. We were after the outcome, and we got the outcome…

“The legislation sits there. It’s through the parliament. The treasurer then has the sole ability to designate. So that trigger is just sitting there waiting to be pulled. It’s not as if the legislation didn’t proceed.

“That would have been a concession. But the legislation’s there. So, yes, I think it’s fair to say that that’s a trade-off, but irrelevant to me.”

‘If you want journalism, you need media companies’

One other major criticism of the code – one that Press Gazette has sought to remedy through its reporting on this matter – is that the terms of values of big tech’s deals with the Australian news industry have remained a secret.

As revealed by Press Gazette’s ‘Google News Shh-owcase’ investigation, publishers have been required to sign confidentiality agreements before receiving money.

Is it healthy for democracy, and trust in media, that two of the most powerful companies in the world are doing huge confidential deals with the largest news publishers in the world?

“Good question,” says Sims. “I don’t think the code changes that, it just meant that deals are done. I mean, Google and Facebook are doing deals with people all the time. Google controls half the apps market, they completely control search.”

These private deals are being agreed in other countries as well. Is that an unhealthy situation?

“I think that whenever big companies do deals with other big companies, the public’s got a right to be concerned. There’s no doubt about that,” says Sims.

“All the code did was make sure there was money going to journalism. And therefore it helped the media companies. It did not increase the market power of Google and Facebook in any way. Because they were in complete control anyway.

“Now, I’m sure they tried to get as much from those deals as they could, and maybe they got the media companies to do a few things they wouldn’t have otherwise. But big companies always do deals with other big companies. I don’t think the code really changed anything.”

Sims adds: “And look, just one other thing, people say – and Google says – ‘By the way, the code just supports current media.’ And I say, ‘Yeah, that’s what it’s point was.’

“You know, because Google says you’re just channeling things for the established media companies – we want a thousand players to bloom on the internet.

“And my answer to that is: The journalists work for the established media companies. You’re really saying, Google, you don’t want people to get their information from journalists.

“Because William works for a media company. If the media company didn’t exist and William started blogging, I’m not sure how William gets paid as a journalist.

“So, if you want journalism you need media companies.”

Photo credit: REUTERS/Jason Reed

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog