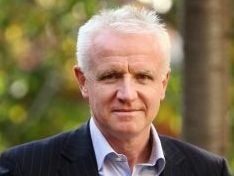

Over 16 years as editorial director and group executive editor of the UK’s largest local newspaper group Trinity Mirror (now called Reach) Neil Benson presided over more than 40 cost-saving restructures.

In this excerpt from his memoir of a 45-year career in journalism, You Can’t Libel the Dead, he offers a searingly honest account of the regional press decline in the UK and offers some pointers for the future of the industry.

My generation of baby boomer journalists has seen the best of times and the worst of times, as we lived through the most tumultuous period of change in the history of the printed press.

We witnessed the death of the hot metal dinosaur and were present at the birth of computerised publishing. More recently, we have ridden the constant shockwaves of the digital revolution and watched in helpless horror as our advertising lifeblood was leeched away.

Whether with enthusiasm or a sense of trepidation, most journalists have adapted to the new world. Some couldn’t, some wouldn’t. And several thousand paid the price of change with their jobs. It has been a rocky, challenging ride.

Journalism has given me enough fun to fill a working lifetime. That said, the battering the news industry and journalists have taken since the beginning of the 21st century has been no laughing matter.

In the early Noughties, after one false dawn, the internet started to have a profound and irreversible impact on news publishing’s business model. The classified advertising that had been the bedrock of the regional press started to leak away to Rightmove, Auto Trader and a variety of jobs boards.

Soon the leak became a dam-burst. In just five years, one of the big regional publishers saw their annual revenue from recruitment advertising alone crash by £100m. But that was just the hors d’ouevre.

In the decade that followed, the tech giants emerged as the dominant publishing platforms – built to a significant extent on content created and paid for by news organisations. They also scooped up swathes of advertising revenue, gutting the news industry commercially.

There’s an argument that says traditional media had it coming. According to our critics, we were lazy incumbents who failed to adapt. We gave away our content when we should have charged for it. We were interested only in racking up profits at obscene rates of return. We cut jobs when we should have been investing in journalism.

Publishers’ fatal mistake – or BBC encroachment?

Some of these criticisms are justified. Others, in my opinion, don’t hold water.

Profit margins in excess of 30% were not sustainable at a time when the internet had begun to shake the industry’s foundations, but it didn’t stop some publishers striving to push them ever upwards. For some, it became a test of their virility to see how high they could go, with little thought for the consequences. And, undeniably, companies should have reinvested more of their profits, years sooner, in the digital future.

But, in my view, the often-repeated accusation that publishers made a fatal mistake by failing to charge for content from the outset does not bear scrutiny.

The BBC is ubiquitous, well-funded (enormously so, when compared with commercial news publishers) and well-established in local markets, via local radio and the behemoth bbc.co.uk website, with its local break-out sections. The BBC invested heavily and cleverly in the web from a very early stage, using their TV and radio strength to promote their burgeoning digital service relentlessly. And they haven’t stopped.

The result is a service which is in many ways excellent, but which has encroached unfairly on local media ecosystems, distorting the commercial landscape, limiting the business models available to publishers and, indirectly, reducing the commercial revenue pot.

At the local level, bbc.co.uk’s content lacks the depth of most commercially-funded publishers, but it has one magic ingredient – it is free.

In readers’ eyes, that makes it an oven-ready, good-enough substitute, should local newspapers attempt to charge for their content.

Paywall experiments

Regional publishers have flirted with paywalls for years. Every time, the experiment was swiftly curtailed as they saw their digital audience crash by around 90%, almost overnight.

In the early days of the internet, there was a saying that: “The only things that make money on the web are the Three Fs – football, finance and… pornography.” These days, I’m not so sure about football.

In my view, paywalls never were and never will be the saviour of the regional press – or, for that matter, the national tabloids, which compete fiercely over a very similar mix of content, principally entertainment news, celebrity gossip and sport. So long as one of them remains free-to-air, so must the others.

At the top end of the market, the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times have had success with paywalls, not because of their news content but because the unique financial data they provide is a must-have for businesses.

The other “posh” papers – The Times, The Guardian and the Daily Telegraph – have, each in their different ways, built respectable subscription-based audiences.

In a highly-uncertain market, one thing seems clear – there is no one-size-fits-all solution to the conundrum of finding a sustainable publishing model.

The answer for the tabloids and the regionals is more likely to lie in a much wider mixture of revenue sources than the traditional combination of advertising and cover price which sustained print for so long.

People and paper pay the price

The internet-driven revenue crash was so severe that job cuts were unavoidable. Over the course of 16 years as editorial director of Reach plc’s regional titles, I was responsible for leading more than 40 cost-saving restructures, as a consequence of which many journalism roles were lost.

Journalists were not the only ones to suffer; colleagues in advertising, newspaper sales and all the back-of-house departments have also felt a great deal of pain.

It used to be a truism among newspaper finance directors that the industry’s two biggest costs were people and paper, so these were the main ports of call when major cost savings were required. But cutting either of them comes at a price.

Lower pagination means less value for money for the reader, which inevitably causes some to stop buying. Raising the price of the newspaper can help to fill the revenue gap but that triggers a further loss of readers. It’s a brutally simple equation – the bigger the price increase, the more readers you will lose.

At the current, mature stage of printed newspapers’ life cycle, circulations and paginations are a fraction of the glory days, which means paper is no longer the major cost-reduction lever it used to be. So the focus falls on people.

You can usually get away with reducing the number of journalists on your books, in the short term at least. Journalists, in the main, are driven by a love of what they do and a commitment to producing a quality product. They will go the extra mile, put in the extra hours, cover for the lost jobs.

But eventually, after multiple rounds of downsizing, something has to give. That something is breadth and depth of coverage.

When big stories break, newsrooms still react, often magnificently. But the everyday coverage – court and council reporting, and the workaday local stories that fill the middle of the paper – has become thinner. Less resource also means less time to plan and to be creative, forcing newsrooms to be more reactive and products to become that little bit more bland.

A single, well-executed cost-saving restructure may go almost unnoticed by the reader. But as the revenue continued to drain away, cost saving became an ongoing necessity. You can’t defy gravity forever – eventually, editorial quality suffers. Society pays a price too, as the press’s ability to fulfil its role as public watchdog is eroded.

Trust down and abuse up

It’s not only the products that feel the pressure. In the era of fake news, “alternative facts” and social media trolling, life as a journalist has become significantly tougher. Faced with an ocean of content, it is difficult for readers to sort fact from fiction, with the result that some no longer trust anything they read, whatever the source.

At the street level, reporters across the UK regularly face abuse, threats and even physical attacks as they go about their job of bringing the news of the day to the communities they serve. Young, female reporters are a particular target. It’s an ugly state of affairs.

Despite all these difficulties, editors and their teams are constantly conjuring up initiatives to help bridge the resource gap and rising to the challenge of building a digital audience big enough and loyal enough to sustain the business in the long term.

The goal I set myself at Reach was to find the new business model for regional titles, which I believe must be based on editorial departments being profitable in their own right. I gave it my all but when I left the company, on December 31, 2017, the new model had eluded me; digital revenue growth had failed to match the boom in audiences, and stand-alone editorial profitability was still some way off.

Reasons to be hopeful

But since then, a number of hopeful signs have emerged. The online audience for regional content has continued to grow, and now typically accounts for around 90% of the total, with just 10% coming from print. The readers who slowly but steadily deserted newspapers have been replaced, with interest, by a new generation who never buy a paper but are voracious consumers of information via their smartphones.

Many titles have more readers now than when I began my career in 1974, and those readers have a strong interest in news, sport and what’s on in their local area – the meat and drink of regional publishing. It seems to me that the path to a sustainable future lies in understanding these growing audiences, engaging with them to cement their loyalty and using their personal data judiciously to provide editorial and commercial services they value and trust.

The Covid pandemic brought its own, particular challenges but the news media responded magnificently, switching from office-based to home working in a matter of days, with barely a blip, and without the reader noticing. It was a great achievement which showed that, when they have to, publishing businesses can move mountains.

Covid has also given regional publishing an unexpected shot in the arm. Newspaper sales were hit during lockdown – although not as severely as some had feared – because people chose to stay safe in their homes rather than venture out to the newsagent’s. But online audiences boomed as readers turned to their local title’s digital channels for the most reliable, up-to-date news on how the pandemic was affecting their part of the world. And revenue has followed, as advertisers realised the most effective way to reach these significant audiences is – just like the old days – via the local news publisher.

There are also signs the tech giants have accepted – late in the day and grudgingly – that they are not just platforms but publishers, with all the implications that has for governance, proper content management and a duty of care to users.

There are signs, too, of a fairer commercial deal emerging for the news media, whose content has helped the giants achieve their position of global super-dominance.

Most encouraging of all, regional publishers are launching new websites and have begun recruiting again, as they pin their strategy – and the future of their business – on their relevance to local communities, based on high-quality, digitally-led content.

As a young reporter, all I had to worry about was taking a good shorthand note, writing my story and hitting the edition deadline. Today’s journalist writes stories, takes photographs, shoots and edits video, creates social media posts, hosts and produces podcasts, understands search engine optimisation and can use digital analytics programs to drive audience growth and engagement with readers.

They produce far more content than my generation ever did, across an array of media platforms. They are smart, highly skilled, prolific, endlessly adaptable, quick to learn and remarkably resilient.

They are the torch bearers for the future of UK journalism. I take my hat off to them and wish them every success. And as they make their way in the industry I love, I hope they have more than their fair share of fun.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog