For earnest supporters of Hacked Off the memoir of veteran diary journalist John McEntee will read like a horror story.

In the book he admits to: making up a fake contributor in order to defraud The Times, pretending to be disabled to secure an audience with the Pope and breaking a confidence with the actor Richard Harris in order to reveal to the world that his son had been in rehab. He also may have played an unwitting part in the deaths of the then oldest man in Ireland and the actor Derek Nimmo. And he once gravely offended Sir Trevor McDonald by calling him a “little monkey”.

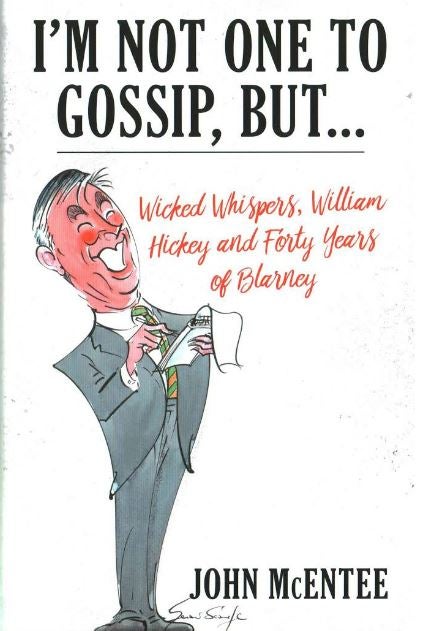

But for others “I’m Not One to Gossip, But”… can be enjoyed as a refreshingly honest romp through 40 years on Fleet Street with one of its most garrulous inhabitants. And it’s also a (very) social history of modern Britain.

While McEntee feels nostalgia for the days of boozy lunches, generous expense accounts and all the rest – he doesn’t spare the dark side of the ‘street of shame’.

Talking over a coffee at the Derry Street headquarters of the Daily Mail he admits that booze ruined many a journalist’s health and career. And in his book he reveals how his former gossip column rival Nigel Dempster once ran over a child whilst driving home drunk.

McEntee’s book begins with his time as a London correspondent for the Irish Press Group and goes on to recount his days working on diaries for The Times, Evening Standard, Daily Express and Daily Mail. In 2000 he was earning £100,000 a year (equivalent to about £160,000 today) as a bylined gossip columnist for the Daily Express.

In 2009 he was made redundant by the Daily Mail but today he continues to freelance for the paper’s Ephraim Hardcastle column.

“I started as a serious journalist believe it or not”, he says. “I was London correspondent of the Irish Press Group in the late 1970s and early 1980s covering really serious stories during the Troubles. In a way it was much more fulfilling, but they were closing the London office, so I started doing shifts on the Londoner’s Diary [at the Evening Standard].”

Asked what his best story was, he recalls tracking down the undertaker who dealt with three IRA members killed by the SAS in Gibralter and discovering that rather than each being killed with a single shot (as claimed) they were “riddled” with bullets.

He adds: “All diary stories are revelations or discoveries, but none of them matter that much. It’s more diverting and showbizzy.

“It’s the one part of the paper where you tend to have to come up with something original. You have to find stories, people tell you things at parties.”

Two of the most amusing episodes in the book involve McEntee being thrown out of parties: at the opening night of the play Art hosted by Sean Connery (after asking the James Bond actor why it was a pay bar) and after being attacked by Angela’s Ashes author Frank McCourt (when he asked what happened to his mother’s eponymous ashes).

Recounting the story of how his fictional Times tipster came a cropper, McEntee says: “There was a culture on some diaries where people paid their wives and so on, it was completely corrupt.

“I invented a fictional contributor who was actually me. I became the most prominent contributor who was invited to parties by the paper at the time. I would say he’s ill, he can’t come.

“When I was on holiday the editor tried to contact this guy, Tommy McCauley, they found the address where the cheques were going to he didn’t live in. Instead of saying ‘you’re even more productive than we thought you were’, he asked me to resign.

“I’m not proud of it but we shouldn’t pretend these things didn’t happen.”

Hollywood actors, politicians and aristocrats have been the daily fare of McEntee’s journalistic life. What does he make of the current crop of reality TV-created celebs (such as Mail Online favourite Kim Kardashian)?

“It’s a lack of achievement. At least people had either written a decent book or starred in movies. A lot of the celebrities now are completely meaningless. They haven’t any clout or hinterland.

“But because of the phenomenom of social media the whole landscape has changed.”

McEntee laments the lack of human contact nowadays between journalist and subject.

“Mail Online has a terracotta army of people writing stuff around the clock. They are writing about people they’re never going to meet. Transcribing stuff from magazines.”

He adds: “Fleet Street was overmanned, over paid and over drunk but the fact was it was fun…

“Today everything is deals with publicists. There isn’t an understanding that you could pick up the phone and ring someone you’ve met who happens to be in the news and talk to them.”

Asked whether he was ever involved in phone-hacking, he says: “The most I would ever do was ask a policeman to help you tracing a phone number of a number plate. That was slightly dodgy.

“But the hacking we saw at News International was never a practice in diaries.”

On the on the subject of paying for stories, he says: “The culture was you pay for information and I see no harm in that. It’s a commodity to be bought.”

The money, like the lunches, is not what it once was. The Hardcastle column pays £80 for a tip which makes it into print (a fee which has not gone up in 20 years).

Those hoping for scurrilous gossip in the book about McEntee’s current editor Paul Dacre will, not surprisingly, be disappointed. But he does recount one anecdote at a features planning meeting at which he admitted to Dacre that he was not wearing a poppy.

Dacre reportedly said: “You fucking Irish. You left the lights on in Dublin so the Germans could bomb Belfast. You refuelled the U-boats off the coast of Galway and you signed the book of condolence for Hitler at the German embassy in Dublin at the end of the war. You treacherous, treacherous Irish.”

McEntee had just arrived at the Mail from the Express at the time and was writing a column called Wicked Whispers.

He says: “Dacre was an extraordinary revelation, a hugely driven man committed to everything he does. Secretly he’s quite a comedian, he pretends not to be. It’s all tongue in cheek.”

Asked what is the key to being a good diary writer, he says: “You can’t be in awe of the people you re writing about. You have to be honest and clear.

“Too many people don’t ask questions and also stand back and almost sneakily observe people. You can’t do that, it’s not honest or fair.”

To make the point he recounts a story about “one of my great heroes”, Helen Minksy – who worked for many years on the Nigel Dempster column – and a story she wrote about bookmaker Victor Chandler’s wife running off with his nephew.

“She called him up and said: ‘I’m your nemesis’. She explained in great detail the story, he wasn’t very happy about it. She said: ‘I’ll call you back this afternoon and we’ll go over it.’

“By the time she called him back he had calmed down. The worst part of that whole experience for him was having Helen Minsly call him and say ‘I am you nemesis’ down the phone. It was the honesty about it. ”

LISTEN TO THIS INTERVIEW AS A PODCAST

“I’m Not One to Gossip, But” is published by Biteback Publishing, price £18.99.

Extracts from the book

Richard Harris and Angela’s Ashes

McEntee befriended Richard Harris in the years before his death in 2002 despite having faced him in the High Court (and lost) in 1986 after he sold the story of his son’s drug problem to the Daily Star.

In the book he recalls asking Harris to come with him to a party to celebrate the publication of the millionth paperback copy of Frank McCourt’s famous ‘misery memoir’ Angela’s Ashes.

Harris: “Frank McCourt! That wanker. I wouldn’t cross the street to piss on him…When you see McCourt ask him what happened to his mother’s ashes. I know he fucking lost them.”

At the party McEntee explained what transpired:

“I introduced myself. He was beaming in delight with the attention. Then, apropos of nothing, I asked, ‘Tell me, Frank, what happened to your mother’s ashes?’ The transformation was instant and extraordinary. He grabbed me by the throat and pushed me up against the boardroom wall. ‘Harris sent you!’ he screamed. ‘Richard Harris fucking sent you. You tell Harris I found my mother’s ashes. You go and tell him that.’

“Having upset the famous author, I was asked to leave the soirée. A badge of honour in my profession.

“At another meeting McCourt admitted to indeed losing his mother’s ashes: ‘Yes, we did lose our mother’s ashes. Malachy and I had too much to drink in a Manhattan bar and we left them behind … but we did eventually retrieve them.’”

The incident with Sir Trevor McDonald:

One of my innovations [on the Express] was a weekly diary in which a celebrity recounted his or her activities in the preceding week. Sir Trevor McDonald promised a diary that failed to materialise. I left a nagging message on his answerphone.

Returning well refreshed from lunch, my secretary said, ‘I’ve got Trevor McDonald on the phone for you.’ Taking the receiver, I used a phrase familiar to my infant children when they misbehaved.

‘Trevor, you little monkey. Where’s the copy?’ I heard a sharp intake of breath. ‘What did you call me? Did you call me a monkey?’

The West Indian-born doyen of newscasters was furious. ‘Trevor, it was a term of endearment,’ I pleaded. ‘Endearment? Calling me a monkey?’

I looked around the London section desk. Two of the female reporters had their heads in their hands. The sub had his fist in his mouth. They were witnessing a car crash. It took all my skills of Irish blarney to placate Sir Trevor. Mercifully, he still takes my calls.

On Nigel Dempster:

Our friendship hit the buffers when I had my own bylined column in the Express. Nigel devoted a quarter page in the Mail to the death of his pet dog Tulip. The story included a photograph of the chihuahua and the prose dripped with pathos. ‘The Dempster household is in mourning … Christmas will never be the same again.’

On reading this, Chris Williams, then No. 3 on the Express (later to be editor), suggested I take a pot shot at Nigel following his over-the-top eulogy for Tulip. The following morning, I carried a small paragraph that read: ‘The Diary is in mourning. Nigel my pet ferret has passed away after twenty-five years of faithful service. I shall miss his little nose sticking out of the bars of his bespoke cage. We shall not see his like again.’

At about 11 a.m., the diary secretary Catherine took a call and, cupping her hand over the receiver, said that Nigel Dempster wanted to speak to me. Assuming that Nigel wanted to mock my piece as very droll, I took the call. I was not prepared for the verbal onslaught. ‘You Irish cunt!’ he screamed. ‘You Irish turd!’ As I tried to get a word in edgeways, Nigel told me he was writing letters of complaint to my editor Rosie Boycott and Lord Hollick, proprietor of the Express. ‘My dog isn’t even buried yet,’ he added, with a voice that suggested he was on the verge of tears. ‘And I’m reporting you to the RSPCA for keeping a wild animal indoors. I shall never speak to you again.’

Five years after his death, I was in the saloon bar of the Wellington pub in Fulham when a young man in a paint-spattered T-shirt and jeans approached my stool as I savoured the creaminess atop my perfectly poured pint of Guinness. ‘Are you a journalist?’ he asked speculatively. ‘Yes,’ I replied. ‘Do you know Nigel Dempster?’ he asked.

Of course I knew the doyen of gossip columnists. ‘Why do you ask?’ I enquired of my new young acquaintance. ‘Because’, he replied, ‘Dempster ran over me in his car while he was drunk.’

It was only then I noticed the slight limp as Dempster’s young victim returned to his seat in the saloon bar. I wanted to know more. His name was Kylie Proctor, then aged twenty-six, a painter and decorator whose right leg still retained the metal supports inserted after Dempster’s red Honda Accord ran over him a short distance from the Wellington.

He was crossing the road with his older sister. He was never to play football again. He will always have a degree of pain but he bears no malice towards Nigel, who he was not aware had died. It was October 1997; Kylie was aged eleven and Dempster was taking a shortcut towards Hammersmith when he collided with the schoolboy. Nigel had a reckless disregard for drink-rules.

Former Express editor Rosie Boycott and the incident with the fish fingers:

She sacked a lot of people; none of them had the pleasure of a face-to-face meeting. Managing editor Lindsay Cook was Madame Guillotine, summoning people to break the bad news and then offering them terms. One, Tom McGee, the City editor, said he had a young family. She winked and suggested that he could be generous in filling in his last expenses claim.

Another, James Hughes-Onslow, said he had a son starting at Eton. Miss Cook asked how he could afford to send a son to Eton on his salary. Hughes-Onslow Jr was a scholarship boy. Shortly after his sacking, James exacted revenge.

Commissioned by James Steen, editor of Punch, to view Rosie’s house in Westbourne Grove, which was then on the market, he did more than Steen had asked. The estate agent arranged a viewing, not knowing James was a disgruntled ex-employee.

In the coming weeks, Rosie and her family were troubled by a noxious smell emanating from the bathroom. It grew in potency and eventually a plumber was summoned. He could find nothing wrong with the drains. Finally, in a recess behind the bath panel, he discovered a packet of rotting fish fingers. Rosie was incandescent.

She got her secretary Tamsin to painstakingly telephone each of the potential vendors who had viewed the property. She hit the jackpot when James – who had used his wife’s maiden name with the agents – answered his telephone brightly: ‘James Hughes-Onslow here.’

Rosie threatened to prosecute for criminal trespass but the story was allowed to slip quietly into Fleet Street folklore.

Modern Fleet Street:

No one drinks any more. No one goes out any more. No one meets people any more. Modern practitioners with their Prêt a Manger salad lunches and their five-a-day infusions at their work stations, their forensic reading of Hello!, OK! and Closer, sit from dawn till dusk at their winking computer screens.

All the national newspaper newsrooms are now filled with Terracotta Armies of earnest young men and women rewriting magazine articles and churning out a grim mince of show business and celebrity stories about people they don’t know and will never meet.

And as for drinking – it’s now confined to the canteen.

As a self-confessed old fogey, I mourn the revolutionary transformation of a once-colourful and quixotic profession.

Gone forever is the once-conventional career path of getting a foot in the door in a local newspaper as a teenager or a job as a poorly paid copy boy on a national title and working your way up. My generation had the benefit of inching vertically on the career ladder, junior reporters moving on to a specialisation – political, medical, social services – or the still-glorious peaks of sports reporting.

Now there is no middle ground. A journalistic Grand Canyon has evolved, marking the gap between the legion of poorly paid youngsters barnacled to their computers and, on the other side of the crevasse, very well-paid star writers, columnists and pundits occupying the distant high-altitude peaks.

There are a few dinosaurs still clinging on in the middle; veteran news reporters and specialists. And for those at the scorched-earth side of the canyon, a university education and a course in journalism are de rigueur for employment on a national title.

And with starting salaries diminished to the early £20,000s, it has become a calling dominated by those who have rich parents able to afford to subsidise London accommodation and other costs.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog