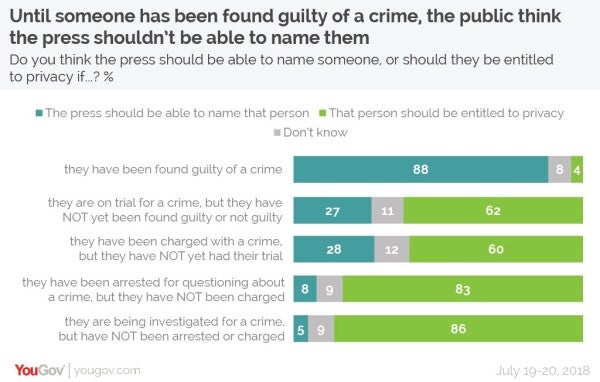

Just one in 20 people (5 per cent) believe the media should be able to name someone who is under investigation by police but has not yet been arrested or charged, as in the case of Sir Cliff Richard, a Yougov poll has found.

Of 1,669 GB adults surveyed in the two days after Richard won his High Court battle against the BBC last week, 86 per cent of those polled said people should be entitled to privacy in such circumstances.

Sir Cliff was awarded £210,000 damages from the BBC, with more still expected to be awarded, after it broadcast helicopter footage of a police raid on his Berkshire home, on 14 August 2014, on its 1pm news bulletin.

In so doing it also revealed police were investigating the 77-year-old singer over an historical child sex assault allegation. Sir Cliff was never arrested or charged and the case against him was dropped in 2016.

Mr Justice Mann said in his judgement, handed down last week, that a suspect under police investigation has a reasonable expectation of privacy.

He said: “As a general rule it is understandable and justifiable (and reasonable) that a suspect would not wish others to know of the investigation because of the stigma attached.

“It is, as a general rule, not necessary for anyone outside the investigating force to know, and the consequences of wider knowledge have been made apparent in many cases.

“If the presumption of innocence were perfectly understood and given effect to, and if the general public was universally capable of adopting a completely open and broad-minded view of the fact of an investigation so that there was no risk of taint either during the investigation or afterwards (assuming no charge) then the position might be different.

“But neither of those things is true. The fact of an investigation, as a general rule, will of itself carry some stigma, no matter how often one says it should not.”

The Yougov poll found that only 8 per cent of people think the press should be able to name someone who has been arrested, but not charged.

Once charged, 28 per cent of respondents believe a suspect should be named – the same number who think the press should identify someone who is on trial before they have been found guilty.

Once they are found guilty, 88 per cent said the press should be able to name them.

Yougov chart on press naming police suspects.

Despite the poll results, newspapers and media commentators have united to back the BBC and the principle of press freedom.

The BBC has said it is considering an appeal and that the judgement “represents a dramatic shift against press freedom and the long-standing ability of journalists to report on police investigations, which in some cases has led to further complainants coming forward”.

Former Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger pointed out that Harvey Weinstein may not have been exposed if suspects could not be named before charge, but said some news organisations needed to “rethink some outdated attitudes to privacy”.

Writing in the Guardian, Rusbridger said: “Here’s a judge apparently saying that, in future, an individual’s privacy rights trump any supposed public interest in openness.

“Imagine not being able to write about Harvey Weinstein for fear of hurting his feelings or damaging his reputation. Where would the #MeToo movement have been without the slow domino effect of one woman after another coming out into public, each one reinforced by the example and bravery of others?

“In Mr Justice Mann’s world, Weinstein would surely have had a safe harbour.”

The Mirror said last week the judgement had “dangerous repercussions for press freedom”, saying a blanket ban on naming police suspects could make it impossible to name a teacher suspected of child abuse.

The Sun went further, calling for Government legislation to guarantee the right of the press to name suspects once they have been arrested.

Sir Cliff told ITV News in an interview after the ruling that he would not have gone through such emotional trauma if he had not been named.

“If the police had found enough to prosecute me, I would have been charged and then I could have been named and if you’re charged, it might take two years, your name is out, where other victims could come forward if it’s true and even then the court of law could pass that person as innocent,” he said.

Picture: Victoria Jones/PA Wire

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog