Channel 4 News international editor Lindsey Hilsum has said she is “anxious” about contributing to the “myth” of her friend and murdered war reporter Marie Colvin in having written a book about her life.

Sunday Times correspondent Colvin was killed in Homs, Syria, on 22 February 2012 after artillery fire hit the media centre building where she was based, reporting on the country’s brutal civil war.

She was killed along with French photographer Remi Ochlik. Her family claim she was deliberately targeted by the Syrian regime.

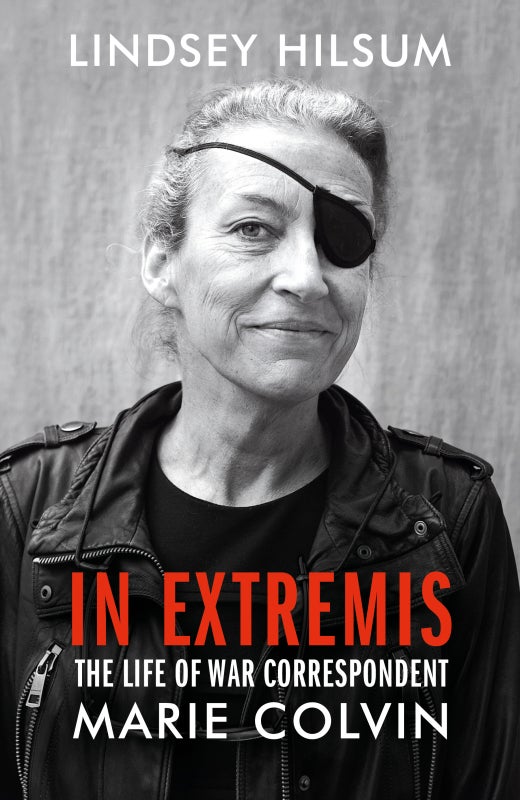

Hilsum said there is a danger that through her book, In Extremis: The Life of War Correspondent Marie Colvin, she is “buying into or helping create the myth of Marie and the glamour of the war correspondents”.

Its release coincides with two big-screen portrayals of Colvin: Hollywood film A Private War, starring Rosamund Pike as Colvin, and documentary Under the Wire, based on the memoir of war photographer Paul Conroy who was working alongside Colvin on her final assignment.

Hilsum told Press Gazette: “I think it’s great that there’s a lot of attention on Marie because it means a lot of attention on journalism and on war correspondents and on Syria and on the things that matter to me.

“I am slightly anxious about contributing to this myth of Marie thing, you build her up as a glamorous figure… But it’s a Marie moment and I hope if she’s up there, she’s looking down and enjoying it.”

The Channel 4 News international editor added: “Obviously Marie’s a very glamorous figure because she’s a woman, because she took all these risks, because she wore the eye patch, because she had one studded with rhinestones for parties, she’s a very romantic and glamorous figure.

“But that doesn’t mean that that’s the only kind of journalism that matters and the only kind of journalism to do.”

Hilsum said the “big need” at the moment is for journalists with a science background who can report on issues such as the environment, and people who have the knowledge to report on finance and economics.

She said there is a “strong argument” that journalists are now too metropolitan-based and that the most important work is being done by those “reporting within their own communities”.

Hilsum said she hopes to ensure Colvin is remembered for her “extraordinary journalism” rather than her “violent and tragic” death.

She said of her book on Colvin: “There’s a lot of her adventures in there – trekking through the mountains of Chechnya and losing the sight in her left eye in Sri Lanka.

“I want people to think about the extraordinary lengths she went to to tell a story, because she was so committed to journalism and to telling the stories of the victims of war.”

Marie Colvin and Lindsey Hilsum in Jenin, Palestine, in 2002. Picture: Paul Moorcraft

Hilsum said she hoped the book would enthuse young journalists about the profession and show “how important it is to tell these stories and to not let things go unreported”.

But she also said the book could be an “example of what not to do” revealing that Colvin struggled to find happiness in her personal life and overcome post-traumatic stress disorder after being hit by shrapnel in Sri Lanka and blinded in one eye – the cause of her famous eye patch.

Hilsum said Colvin lived her own life “in extremis”, not unlike those on whom she reported. She wrote in the prologue of her book that Colvin “always went in further and stayed longer”.

Hilsum spoke to her friend by Skype just hours before she died as she gave an interview for Channel 4 News from Baba Amr, the besieged neighbourhood of Homs in Syria.

Hilsum and two other journalists had decided not to enter Baba Amr but Colvin went in – and fatally returned a second time after filing her story.

Colvin knew her foreign editor and friends would have told her not to go back, which is why she did not tell anyone about her decision, Hilsum said, but she added that she understood Colvin’s motivation.

“She felt a huge commitment to tell that story and she felt that by leaving she was in some way abandoning the people of Baba Amr and that was surrendering to the narrative of the Syrian Government which said there were only terrorists in the enclave of Baba Amr and there were no civilians.

“Marie felt that she had to be there to report that that was a lie. But, of course, I wish she hadn’t gone back.”

Following Colvin’s death, and the subsequent kidnapping and killing of US journalists James Foley and Stephen Sotloff in Syria, Hilsum said she was shaken and it had made her and other foreign correspondents “think twice or three times about the level of danger to which we expose ourselves”.

But in what Hilsum called an “alarming development” the threat has since shifted to an unexpected place: the European Union.

“Obviously as a war correspondent you understand that you might get killed,” she said. “It’s a question of judgement, but you’re taking a calculated risk.

“But what we’re seeing at the moment is investigative journalists who are uncovering the links between corrupt politicians and organised crime – they’re the ones who are really most in danger at the moment.”

Investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was killed by a car bomb in October 2017 near her home in Malta, Slovak investigative journalist Jan Kuciak was shot dead in February this year in Slovakia, and Bulgarian TV reporter Viktoria Marinova was raped and murdered last month.

Hilsum wrote In Extremis over the course of about three years, with a four-month fellowship at Stony Brook University in Long Island – near Colvin’s family home – and another three months off from her day job at Channel 4 News last summer.

After carrying out 114 interviews and reading 300 of Colvin’s notebooks and diaries, Hilsum said the hardest part was knowing when to stop researching and start writing.

“I could have interviewed 214 people because she had touched so many people’s lives,” she said.

Another difficult part of the process was the frustration of not being able to phone her friend and just ask what had happened.

“It’s a very strange thing to get to know your friend better in death than in life, but that’s what happened, because if she had lived I would never have read her teenage diaries.

“There would be times when I would miss her so much and also times when I was just like ‘why can’t I just ring you’?”

Pictures: Paul Moorcraft

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog