Audiences want news and opinion to be clearly distinguished from each other, according to research on news impartiality commissioned by Oxford University.

The study also found that journalists’ language use in headlines and showing emotion in TV reporting could be perceived as bias.

Groups of about a dozen “engaged digital news consumers” from the UK, US, Germany and Brazil, totalling 52 people (aged 20-34 and 35-60), from across the political spectrum and matching each nation’s ethnic diversity, took part in the research between 11 February and 5 March this year.

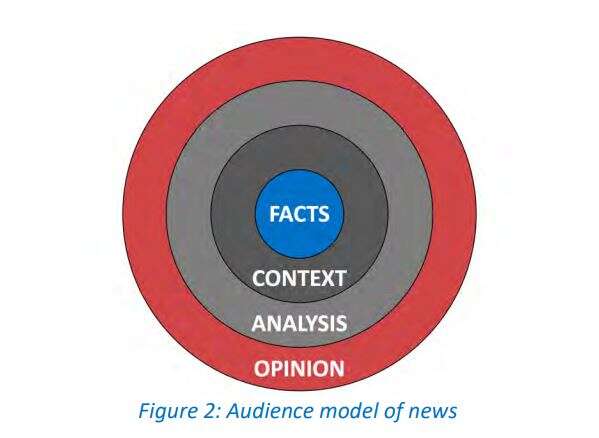

A report on the findings, published this week, found that research participants supported a model of news that had neutral facts at its core, with context, analysis and opinion layered on top (as pictured below).

From: The Relevance Of Impartial News In A Polarised World

The report, The Relevance Of Impartial News In A Polarised World, was authored by JV Consulting and commissioned by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford.

New UK-based TV station GB News has so far struggled to attract a large audience with its opinion-based take on news and this week altered its offering with the introduction of traditional half-hourly news bulletins.

‘Audiences value opinion as a supplement to facts…’

The report said audiences “hold the production of news to a high standard” and want it to be factual and impartial, as well as “clearly differentiated from opinion”.

“This means the news industry should be careful to signpost the different layers of news, clearly differentiating news from opinionated content, particularly where the distinction easily blurs,” the report said.

Newspapers are seen as authoritative sources, but some younger audiences feel many newspapers “represent an older generation and old social values that they do not share”.

Editorial and opinion are signposted in print, but this becomes less clear online, “which can undermine perceptions of impartiality”, the report found. Opinion, where clearly marked out as such, is “widely valued” by audiences, helping them to “make sense of the news”.

“Audiences value opinion as a supplement to facts but generally want the facts to be established first. They worry about blurring of the two,” the report said.

It quoted one Twitter user as saying: “The news used to tell us what was happening and the public would determine how they felt. Now the news tells you what to feel and the public has to determine what is happening.”

Participants said social media offered ease and convenience for finding the latest news, but they also saw it as unreliable and carrying a risk that the news shared might not be accurate, let alone impartial. The “feed structure” also makes it hard to distinguish news from opinion, they said.

Although social media is seen as being “inherently opinionated” and lacking in quality control, “people make allowances for this marketplace nature”, the report found, with users attempting to create an “impartiality of sorts” by selecting from a wide range of views.

“In social media, distinguishing between news and opinion is not easy because of the lack of cues, which some people consider a problem,” the report said. “Some worry that opinionated content is contaminating news. Others, though, simply assume opinion is the default in social media.”

There were similar views on Youtube videos and podcasts.

However people appear to be less concerned over the impartiality of news sources on aggregator platforms, such as Google News, perhaps, the Reuters Institute suggested, because these platforms are designed for news and so are not “cluttered with other content”.

TV news is viewed very differently in the US and UK. In the US, national news programmes are “filled with opinion”, although some “dislike the argumentative tone, which can be divisive and contributes to political polarisation”, the report said.

In the UK, people broadly want scheduled news programmes, such as bulletins, to maintain impartiality in their coverage. “Informal, chatty styles can make news more engaging and accessible, but carry greater risk of presenter bias, although this is forgiven if unintentional and not systematic,” the report said.

Radio bulletins are broadly felt to be impartial, while “discussion, debate and phone-in formats are accepted as opinionated, in line with the values of the station brand”.

Language choice signals bias

“Audiences said headlines can signal the sentiment – and therefore the level of bias – in a report,” according to the Reuters Institute report. Words interpreted as being alarmist, such as “climate emergency”, could be viewed as taking a side.

“People extrapolate from single words and phrases to form a view of the entire coverage,” the report said. “Most people said they prefer neutral language, but more emotive terms do appeal when a particular perspective resonates with the views of the audience.

“Zealous adherence to impartiality can make for dull reading.”

Emotion from TV reporters ‘risks impartiality’

TV journalists showing emotion in their reports is welcomed by some, particularly among younger audiences and those on the political left, with audiences tending to be forgiving of a reporter who is “overwhelmed in the moment”, such as tearing up.

This emotional display can help the audience connect with the story by arousing empathy and it can make news more compelling,” the report said.

“Emotions in formal broadcast news formats are still generally frowned upon, but tend to be more accepted in more casual formats. The risk, though, is that the emotion reveals partisan views.”

This is because displaying emotion is seen as a “tacit personal comment on the story”, the report said. “It may be accepted when the sentiment is shared by the audience, but it is a problem when the audience feels differently about the subject.”

GB News presenter Guto Harri’s taking of the knee at GB News (pictured top) caused a stir among its viewers, many of whom opposed the gesture. Harri was suspended by the channel and later quit.

The report said: “There is a tension between making news more compelling, through emotional reporting, and potentially losing objectivity and trust. The balance for news organisations depends on whether they are trying to appeal to a wider or more niche audience.

“Formal formats, and political coverage, need to tread more carefully.”

Three main risks to editorial impartiality

The study found that risks to editorial impartiality came from three directions:

- “Bias of personal views: The views and opinions of the journalist or presenter slipping into the news, be it in what is written/said, or in emotions revealing too much, whether accidental or intentional, conscious or unconscious. This can include getting caught in ‘groupthink’ where the bias of the bubble of family, friends or colleagues is not noticed.

- “Bias of false balance: Being unfair through applying the false equivalence of alternative views that have no merit because they are discredited by science or opposed by law. This is a problem of inclusion.

- “Bias by omission: Not covering a point of view or silencing a voice, which risks people being marginalised and not feeling represented. This is a problem of exclusion. It is the most disliked form of bias because it denies people agency.”

This last point is said to be “the most troubling to audiences, in part because it is the least obvious breach of impartiality”. The report said that over time it can corrode trust, “particularly in audiences who feel their views are being suppressed”.

The report said: “While this is experienced more on private tech platforms, it does impact on the traditional media brands that use these platforms to distribute their content, and some people feel it disproportionately affects views on the political right.

“Journalists and news organisations need to think carefully about their position in the market, the trust they have built, and how that may be impacted by deviations from impartiality.”

It added: “Journalists and news outlets increasingly will need to decide where they stand: the facts layer of news, bound by accuracy and impartiality, versus opinion; and alignment with younger people’s attitudes on moral issues versus reporting all views with impartiality.”

Picture: Pixabay

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog