Fierce rebuttals to stories about the Government’s handling of the pandemic are a new challenge for journalists that verges on “trolling via government press offices”, the Guardian’s head of investigations has said.

Paul Lewis said he saw echoes of Donald Trump’s relationship with the media in the UK government’s communications operation during the Covid-19 outbreak, having spent several years as a reporter in the US.

Since last month, a number of government departments have published lengthy blog posts – sometimes up to 3,000 words – responding directly to news stories and typically decrying the journalism as inaccurate.

Lewis (pictured) told Press Gazette the new approach is “much more aggressive than anything we’ve seen in the past”. It follows the launch of a counter disinformation unit for coronavirus in early March.

‘I thought that was really crossing the line’

Among journalists to have faced criticism from government are the BBC’s Lewis Goodall, Financial Times’ Peter Foster, the Sunday Times Insight team and the Manchester Evening News’ Jennifer Williams.

In its response to Williams’ report that the Government had stopped funding a scheme to keep homeless people off the streets during the pandemic, the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government said the article’s claims were “simply wrong”.

It added: “This misleading information causes unneeded anxiety and confusion for vulnerable people at an already difficult time” (which Williams tweeted was “through the looking glass”).

“I just thought that was really crossing the line,” Lewis said of the Government’s response to Williams. “Some of this verges a bit on trolling via government press offices.”

He added: “…the complaint about misleading the public is one that can justifiably be made against the Government.”

A recent Press Gazette poll found two-thirds of respondents rate the UK Government’s Covid-19 media relations operation as poor or very poor.

Lewis said he found it “hard to believe” that civil servants “would all be comfortable with what’s going on”.

“I would like to think that if the civil servants and press operations feel like their arms are being twisted, or feel like they’re being pressured into what feels to them like propaganda, then they stand up to it, because it’s the thin end of the wedge,” he added.

“It’s in all of our interests that we have a civil service that is independent and as committed to the facts as journalists are.”

‘Secrecy and spin’

The Guardian faced its own strong rebuttal from Downing Street after revealing that Boris Johnson’s special adviser Dominic Cummings had been attending meetings of Sage (Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies).

“When we ran that story, the Government’s response to us was staggering,” said Lewis.

“They called the story ludicrous. And they referred to what they alleged was a public distrust in the media. I mean, really quite extraordinary for Number 10 to respond in that way.

“And when they intimated that [Cummings] was just an observer and that there was nothing unusual about a political adviser from Downing Street attending Sage. Well, there’s two answers to that.

“One is he wasn’t just an observer, he was contributing in meetings – and we’ve had that confirmed from other people who were there in the room – and two, this was the first time any special adviser from Downing Street had ever attended Sage meetings…

“People can definitely argue about the merits, or the pros and cons of having him there, but I think the main point, from our perspective, is that it was important to reveal that he was.”

Lewis said the pandemic had exposed “some of the weaknesses in societies around the world”, adding: “In the UK it’s really shone a light on the secrecy around government.”

“If you had to characterise the Government’s communications around this, it has been a combination of secrecy but also spin,” he said.

“I just think it’s been disappointing that in this time when we really do need maximum transparency and honesty and openness – that’s how societies function best in times of crisis – that we have not seen that.

“And that’s where journalists come in, because if governments are not being sufficiently transparent or open, then that’s where particularly investigative reporters have a role to play, to prize out the information.”

‘Sourcing up’ to cover the pandemic

Lewis, 38, took on the role of head of investigations in January. He has spent nearly 15 years at the Guardian, including stints as the title’s Washington correspondent and associate editor.

It was in mid-March, when the scale of the Covid-19 story was becoming clear in the UK, that the investigations team decided to dedicate a “sizeable portion of our time and resources” to the pandemic story, Lewis said.

Covering the pandemic has been the “primary focus” of the seven-strong investigations team over the past two months, with three more journalists brought in to help with the coverage.

Where investigative reporters usually “live in the long grass” and can take months or even years to bring a story to publication, the coronavirus has seen the team work on turning stories around more quickly.

“The very nature of this story – it’s so fast moving, so consequential – that I think it’s inconceivable that you would ever sit on a story for too long,” Lewis said. “You have to get it out straight away.”

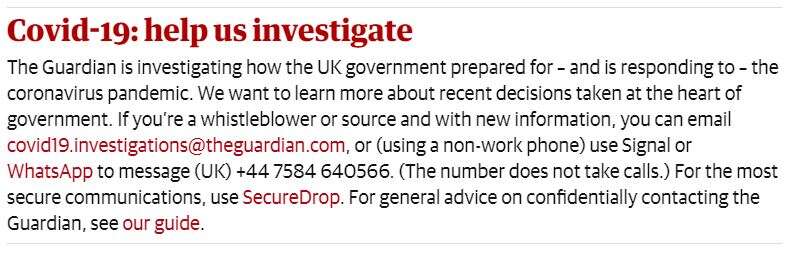

The team had to “source up” to cover Covid-19, gaining confidences in Whitehall and among the scientific community. Part of this process included embedding “get in touch” widgets in stories (pictured below), which Lewis said had generated “a great deal of tips and leads”.

“What we’ve found – and I think all journalists know this – is that once you build up some momentum and start breaking stories it’s often the case that stories beget stories and more and more people come on board,” he said.

“This sounds a bit clichéd, but it used to be much more about journalists finding sources and increasingly it’s about sources finding journalists. And you’ve got to make it easy for people to get in touch with you.”

Among the articles published by the team so far are a deep dive into the inside story of the Covid-19 crisis and a collaboration with ITV News about “chaos” at a UK warehouse stockpiling personal protective equipment.

Lewis said he had been working “flat out” from home, and finding, like most journalists who are reporting while under lockdown, that it is harder to detach when your office is also your house.

But he added: “I’m very lucky, I’ve got a little baby and it’s the most incredible way of de-stressing, spending time with an infant.”

He said daily video calls with the team served not only as a means for organising and managing workloads, but also as an important social catch-up and a “good way of making sure everyone’s doing alright”.

Another challenge of reporting during lockdown is not being able to meet sources in person, Lewis said, which is normally the best way to put them at ease and get them talking.

“I have had a few discreet socially-distanced encounters with sources, but for the most part you’re restricted to chats on Signal, or phone calls via Whatsapp, and that’s just a different kettle of fish.”

‘The first draft of history has to happen quite quickly’

Recent polling has shown a worrying trend that public trust in journalism is falling at a time when people are more reliant on it than ever.

A recent Press Gazette reader poll showed half of respondents believed public trust in journalists has fallen since the coronavirus outbreak began. While a recent Yougov poll commissioned by Sky News showed TV journalists and newspapers were behind politicians in terms of trust.

But research by the Reuters Institute for Journalism at Oxford University found that more people thought The Guardian was doing a “good job” of covering coronavirus than any other UK national newspaper.

Journalists have faced claims that during a time of national crisis they should be more supportive of the Government and not seek to undermine its message, but it is not a position Lewis agrees with.

“I think it’s the reverse of the truth,” he said.

“I think in times of crisis you need more accountability journalism, not less. And I think if you suspend holding powerful figures to account in a period of crisis then you’re in really dangerous territory.”

He added: “The idea that we as reporters would wait until mid-2021 before conducting a post-mortem of what we think happened – I think that would have been really irresponsible.

“The first draft of history has to happen quite quickly. And when you have good reporting, it helps hold governments to account and they often are quite responsive to that reporting.”

He went on: “I think if you look at the scrutiny, people have applied to the emerging testing, contact tracing operation, it means the Government knows that any mistakes that are made will be noticed and [it] will be responsive if and when we do report stories along the way.

“But I think that’s part of the ecosystem of democracy isn’t it? Mistakes are made, journalists often draw attention to them and governments try to respond. I don’t think anyone should be uncomfortable about that process. I think people should be grateful that it exists.”

Read all Press Gazette’s coverage of the coronavirus pandemic and the news industry here

Picture: Guardian

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog