When writing a memoir about my 25 years in local newspapers I wanted to capture two elements. One was my life in the newsroom: the stories I covered, how the job affected the rest of my life.

The other element was the story of local papers, from my first day in a newsroom in 1995 to my redundancy at the end of 2019. Longer, actually – the epilogue covers 2020. This aspect of the book has fewer laughs.

I describe how the Cumbrian papers where I spent most of my career – the daily News & Star and the weekly Cumberland News – were flying high when I arrived. They had a huge reach. It seemed as if everybody in the region read them.

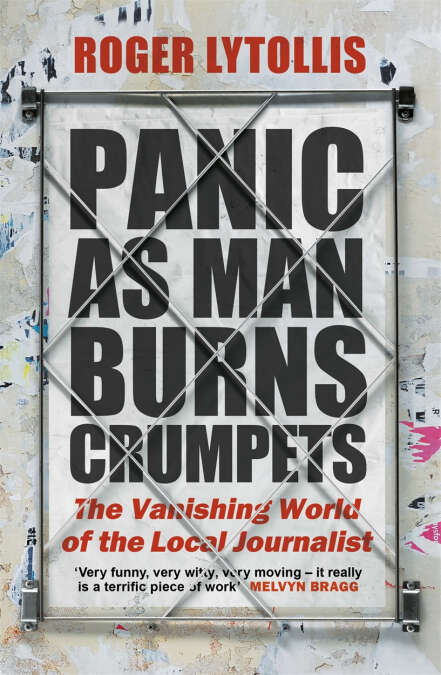

Scroll down for extract from Panic as Man Burns Crumpets

By 2005 the Cumberland News was selling slightly more copies than 10 years earlier and the News & Star slightly fewer: 39,000 and 26,000 respectively.

Then began the slump that’s been mirrored across the UK’s regional press, with hundreds of papers closing and thousands of journalists made redundant.

By the time I left, the News & Star was selling fewer than 6,000 copies a day.

I put much of this decline down to the rush by local papers to give away their content online. Newspapers made a lot of money from the cover price and advertising. Publishers creating a free alternative to their papers always seemed a questionable business model to me and most of my colleagues.

Those of us who argued against it were regarded as naive by managers who thought that online ad revenue would cover a big enough chunk of the loss of newspaper sales and advertising. They weren’t to know that Facebook and Google would hoover up most of this cash – maybe they’d have been right otherwise.

But I still have my doubts that giving away your product could ever be a successful policy. In my book I mention how publishers that are a decade or more into their digital transformation continue to make the vast majority of their money from print. Reach is the UK’s biggest news publisher. As recently as 2019, print provided 84% of its income.

After a few tentative experiments, more publishers are looking to subscription models as a means for websites to pay their way.

Newsquest and JPI Media are among those treading this path. It’s just a shame that people are being asked to pay for local news only after years of having it for free, and when publishers have slashed staff numbers, with a predictable impact on quality.

I was made redundant by Newsquest. The company bought CN Group – one of the last independent newspaper publishers – in 2018. CN had made redundancies in the previous few years but Newsquest took this to spectacular levels. Its six papers in Cumbria now have no photographers, no sub-editors, no feature writers and one sports journalist. Many of the remaining reporters are trainees or have recently qualified.

[Read more: JPI Media to expand online into eight major UK markets with Local TV partnership]

This year Newsquest, Reach and JPI Media are all recruiting journalists for their websites. The numbers are a fraction of those made redundant in the past decade, but it’s a step in the right direction.

The question is the same as it’s been for at least 15 years. Are enough readers willing to pay for local news, whether through subscriptions, donations, paywalls, or buying one of those old-fashioned things called a newspaper?

Maybe, if it’s worth paying for. If publishers have enough staff, including some with the experience to know their patch and to guide the many newcomers. And if publishers trust that readers want to read local news and features, not press releases and clickbait.

Paying for journalism shouldn’t be seen as a strange idea. It might even reduce the onslaught of online abuse against journalists by challenging the view encouraged for too long by publishers: that their work is worthless.

Extract: Panic as Man Burns Crumpets

All I’d ever written was columns. On my second day, the features editor disturbed this tranquil existence. ‘A survey’s been published claiming that lorry drivers are ditching fry-ups for healthy options like muesli,’ he said. ‘Go to the local truck stop with a photographer and ask drivers about it.’

An obvious truth that I’d been denying suddenly hit me. If I was to be a journalist, I would have to speak to people. This was bad news. I’d spent my three years at university largely in my room. Before going to the kitchen or bathroom I’d stand with my ear to the door, emerging only when it sounded as if nobody was around. When getting on a bus my face would burn at the thought that anyone might be looking at me.

I’d been best man at my brother’s wedding, agreeing to do it only on condition that I didn’t make a speech. In his speech he referred, sympathetically, to my dread of public speaking. My face burned again with self-loathing.

Thinking you’re worthless while assuming that everyone is concerned with you is a strange cocktail of low self-esteem and arrogance. Whatever the psychology behind it, my life was built on avoiding people. And my dream job demanded that I seek them out.

A photographer drove us to the truck stop by the M6 on Carlisle’s northern edge. My stomach churned as if I’d just eaten a fry-up and muesli sandwich. I’d had an idea, which I shared with the snapper en route. It was possibly the best breakfast-related idea in the history of CN Group.

‘None of these lorry drivers are going to like muesli, are they?’ I said to him. ‘So why don’t we stop and buy some, then you can photograph them holding it and pulling faces as if they’re going to be sick?’

He replied with a scowl. At this point I lacked the confidence to assert myself. I should have insisted that we bought muesli, even though I’d have needed to jump out of a moving car to do so.

We arrived at the truck stop. I wondered if I’d be able to get away with writing a column instead of a feature. A few light-hearted observations about the waistlines of the drivers I saw and some quips about Yorkie bars? Maybe not.

We walked in. The photographer told the manager who we were and what we wanted to do. She raised no objection to me interrogating her customers. I looked around. It reminded me of being in a nightclub: wanting to speak to people but not having the nerve. I had never chatted anyone up. And none of these gentlemen looked like my type at all.

I couldn’t remember the last time I’d engaged a stranger in conversation. But I either did it right now or returned to the newsroom empty-handed, told the features editor that I’d been too shy to approach anyone, and saw my journalism career end after a day and a half.

I wandered across to a lone driver and murmured an elongated ‘Er . . .’ He looked up. My spiel was along the lines of ‘Excuse me, I’m a journalist at the local paper. I’m writing about a survey which says lots of lorry drivers these days are eating muesli instead of fry-ups. I’m asking drivers about it. So, how about you – have you swapped fry-ups for muesli?’

‘You what?’

His reaction was only partly due to my machine-gun delivery. It was an early lesson that the public aren’t waiting for a journalist to turn up and ask about an issue that may have as much relevance to them as the breeding cycle of monkfish. But he talked to me. I wrote down as much of what he said as I could, having no shorthand at this stage. Then I talked to another couple of drivers. They were fine. It was fine. What had I been worried about? The public were lovely!

As we walked back to our car, I saw a driver getting into his truck. Buoyed by my newfound gregariousness, I jogged towards him and called, ‘Excuse me!’

‘Fuck off,’ he said. ‘I don’t give lifts.’

This is an extract from Panic as Man Burns Crumpets: The Vanishing World of the Local Journalist, by Roger Lytollis. Published by Little, Brown.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog