Donald Trump, Kim Jong-un, nuclear threats, Bashar al-Assad, poison gas, Vladimir Putin, Islamic State, terrorists driving trucks and cars into innocent people, and radicalised Islamicists detonating devices that kill more than 20 concert goers.

Whatever fears people may have had about fake news, it’s nothing to how spooked they are now by real news.

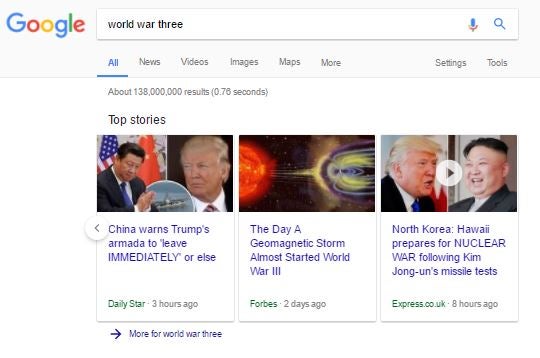

Searches for “World War Three” on Google reached their highest ever level last month, as did ones for “nuclear war”. If you’re thinking of a career change, there’s never been a better time to retrain as a stress counsellor.

But before we all run into the street holding our heads and shrieking in a communal impersonation of Edvard Munch’s painting ‘The Scream’, I’d like to offer a few tranquillising thoughts regarding international willy-waving and the apparent threat of Trump and North Korea coming to nuclear blows.

I say apparent because it is at least worth toying with the idea that the US, and China, both of whom are bringing pressure to bear on Kim Jong-un, might actually know what they’re doing. The reason for Trump’s belligerence, and China’s economic threats to Pyongyang might, for example, be that intelligence tells them that such pressure may lead to a military coup to remove Kim.

I suggest this not because I have access to any intelligence other than my own, but because of my first rule when reading reports of loud and public threats between states: that the ostensible game is not the real game. Other, deeper motives, invariably unreported, are often at work.

Of course, if I’m wrong then by this time next week we’ll all be reduced to radioactive dust. But at least I won’t have spent the last seven days of my life obsessively searching ‘Armageddon” on Google.

Unless you subscribe to one of the more impenetrable foreign policy websites, you won’t get such thoughts from your media. News reporting is now, the immediate reporting of what is on the surface, not the undercurrents. It doesn’t see its job as to sooth; rather to agitate and stir.

And, today, news pours from every paper, magazine, and device 24 hours a day. It is incessant, inescapable, and literally in your face every twitchy, device-checking moment. And that’s why I think that, while there are tens of thousands of courses around the world teaching journalists how to report, there’s at least as big a need for teaching readers and viewers how to consume news and still retain their sanity.

As far as mainstream media goes, people need some of the instinctive scepticism of experienced journalists when they come across news. What’s the source for this? Why are they putting it out now? Is this story a genuine development or just propaganda from some government, politician, company, or pressure group?

I’d like people to know that when reporters describe something as a ‘crisis’, ‘disaster’, or ‘dramatic’, it’s generally nothing of the kind, just the routine ups and downs of life; and that stories about ‘public outrage’ are often triggered by nothing more than a few dozen people getting irate on Twitter.

I’d like people to know that stories based on what someone has said can normally be disregarded until something concrete has actually happened.

(This is especially true of ‘row’ stories, the reality behind which is often that Person A has made a statement and a known or anticipated opponent, Person B, is telephoned, and asked to comment. Their inevitable criticism and Person A’s original words are then presented as a ‘row’.)

I’d like people to know that rolling news channels’ need for 24 hours of content leads to exhaustive coverage of everyday stories that makes viewers think the events are more significant than they really are.

Above all, consumers need to remember the first two laws of interpreting news: that situations are rarely as serious as campaigners and activists say they are, and that news is a construct of real life and not an accurate mirror of it.

All this applies to professionally produced news, but these days that’s not even the half of it. There is also the minute-by-minute outpouring of personal and community news and postings from contacts on social media, mixed in with a fair amount of rumour-mongering, conspiracy-theorying, boasting, admiration-fishing, virtue-signalling, and sympathy-hunting – much of which is not always obvious for what it is.

And the volume of this traffic can be overwhelming.

Marshall McLuhan was right about the global village; what he didn’t anticipate was that everyone would be trying to talk at once. Given that study after study has shown that those who spend the most time on social media are generally the least happy, it is pretty obvious that how to use social media and how to interpret messages on it is something that should be taught in schools, along with how to read and view mainstream news.

We now all live in a sort of media hot-house, the like of which has never been seen. Is it not time that schools and colleges train students not only in online safety but in how to read, discern, and make intelligent sense of the news and messages they are receiving through their devices every moment of the day?

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog