Children’s news titles have been a rare publishing success story during the pandemic, growing subscribers as they reported on the biggest crisis of a generation to its most sensitive audience.

The Week Junior and First News were able to continue printing throughout lockdown as staff worked remotely, and avoided the furloughs and pay cuts that have plagued news titles for adults.

In fact both launched new digital editions during the height of the pandemic, with The Week Junior also landing in the US.

In the UK, The Week Junior magazine has seen its circulation climb by 22% year-on-year to more than 85,500 copies a week (ABC figures to June). Paid subscriptions are up by more than 10,000.

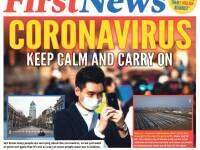

At First News home subscriptions have doubled, editor Nicky Cox told Press Gazette, with the order value from schools also up 59% year-on-year. Last year it sold more than 62,000 copies per week (it’s next ABC circulation audit won’t be carried out until the end of the year).

An independent survey has put the weekly newspaper’s readership at more than 2.6m, up 17.5%.

The Week Junior, which launched in November 2015 as a younger sibling to news digest The Week, but with more original reporting, has continued to grow year-on-year since it was first audited by ABC in 2017.

Covid-19 crisis ‘mindset change’

The Week junior editor-in-chief Anna Bassi said she believed that despite the coronavirus crisis the title would have seen an jump in sales anyway as “there didn’t seem to be any sign of things slowing down”.

But she said parents’ concerns about keeping their children engaged and occupied during UK lockdown, which forced families to stay home, has likely been behind the increased demand for the news magazine.

Bassi said the title’s growth had historically come from word of mouth and suggested that “at a time like this, when everybody’s desperately searching for the right thing to give their child,” parent to parent recommendations would have played a part in the sales kick.

“I think we’ve seen a huge bump precisely because it’s something that’s really needed at the moment, more than ever perhaps,” she added.

First News editor Cox said there had been a definite “mindset change” brought on by the Covid-19 crisis and parents had realised that “their children do need to be part of the conversation that’s going on” to stay informed.

“Kids were so massively affected, probably more than anybody really, with what was going on because their whole world just stopped,” she said.

“They couldn’t go to school, they couldn’t go to clubs, they couldn’t see their friends – they couldn’t even see their grandparents some of them – and children needed information, not just from their parents but directly to them.”

Print still ‘leads the way’

Print remains the primary focus for both The Week Junior and First News, which use their online presence to market subscriptions, but both launched a digital edition alongside print during lockdown.

At First News this ran from the date schools broke up in March through until the summer holidays.

Said Cox: “It was important to us that we were still able to make sure that children were getting reliable information in a way that they could understand, which is what we do. We give the background, we make sure that they can digest the information correctly and accurately.”

In fact First News went further than this, working with Number 10 to create public information notices for children (as pictured below).

The funding was “significant”, Cox said, and helped make up for the loss in advertising from pulled films and days out that were no longer viable.

The Week Junior did not receive funding for government health notices but Bassi said it only experienced a “slight drop off in advertising” that hadn’t been “quite as bad as we anticipated, and certainly not as bad as perhaps other magazines have experienced”.

The ad spaces for the next issue had already been sold when we spoke.

The title’s Summer of Reading advertorial in July also sold out, serving not only to encourage young people to read more and find some escape in literature, but also to support book publishers who had been hit hard by the pandemic and with whom the title has a very good relationship.

Bassi said she had expected new subscribers to drop off after the first six issues, which are free, but instead they stayed with the title. She said it had about 72,000 subscribers at the turn of 2020 rising to more than 94,000 last week (commencing 10 August). “It’s been astonishing,” said Bassi.

Both editors agree that parents like to see their children reading a physical copy of their titles, with screen time typically going up during lockdown.

“It’s definitely something that parents like to see children doing: reading something physical,” said Bassi. The Week Junior had “always been an antidote” to screens, she said, but was not meant to be positioned as better than online activities, rather sit alongside it.

Cox said that although there has been an uptick in digital readers with the launch of the digital edition, “print leads the way hugely for us”.

“I think parents like to see their kids reading the newspapers and actually having something physical in their hand rather than sitting in front of a screen… and kids do too,” she said.

Reporting the pandemic to children

Covering the coronavirus pandemic has put both titles to the test.

At The Week Junior, reporting of the weekly death toll was soon abandoned.

“When the death tolls and the infection levels began to mount dramatically we decided that we couldn’t really continue to report on those numbers every week because it was just too frightening for our readers,” said Bassi.

“I think with any major events – and the only thing I can compare this to, and it isn’t really a comparison, but we’ve had to write about a few terrorist attacks – they are obviously very frightening and children feel quite powerless, and worried about ‘Will I get caught up in attack? Will this happen to me?’

“I felt with coronavirus we couldn’t really put it into some sort of proportion for them that would make them feel better, so we decided then to quickly pivot and started writing about the kind things that people were doing for each other.

“So it was about acts of kindness and generosity, celebrating heroes, talking about the wonderful things that people are doing to be with their community when they were separated… and all the lovely posters of rainbows in windows.

“And then also, and we had to be a little bit careful about this, looking out for the very small silver linings as well. Most news for a couple of months was obviously connected to coronavirus in some in some way, but there were, within those stories, the reduction in pollution, the revival of some animal species, or the fact that you could hear birds singing, which children possibly had never woken up to before. So we were able to pinpoint… some of the positive stories.”

Bassi said checking stories rigorously for accuracy and tone is part of the process at The Week Junior.

“We’re not hysterical, it’s very calm, and I think parents look to us as a trusted source of information for their kids,” she said. The title also avoids speculation in its coverage.

“A lot of news a lot of the time is speculative news these days. We try to avoid speculation. It’s really about reporting on the known facts rather than what we think might happen or what somebody said could happen or the latest leaked announcement from the government.

“We do try to wait until things have actually happened before we write about them in most cases.”

In a similar vein, Cox said the worry came when children were “let loose on the general news” which is aimed at adults.

“There is an element of stories being sensationalised and everything else because it sells doesn’t it,” she said. But while adults know this and are capable of interpreting the news, “children take things at face value”, therefore it’s “really important they get to see a cool, calm, not sensationalised version of what’s going on.”

She added: “We don’t lie, we don’t want to pull the wool over their eyes at all, we’re absolutely honest and truthful about what’s happening, but we always put it in context.”

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog