A victory for men? A defeat for women? A licence for sex offenders? A witch-hunt? A time to name and shame? A time to change the law?

One man is found not guilty of a series of sex offences and half the population dashes to the keyboard to denounce the other half. After seven hours trudging through the quagmire of the papers, the blogosphere, legal websites, feminist websites, misogynist websites, the mud on my boots is so thick that I can barely move.

How did we become so cruel, so vitriolic, so bloody stupid?

Two years ago a 15-year-old girl and her mother went to the police to complain that the actor Michael Le Vell had raped the girl when she was six and sexually assaulted her on a number of other occasions over the next eight years. Le Vell was arrested the next morning and questioned for a number of hours. Once the police had completed their investigation, the file was passed to the CPS, which decided not to proceed with the case.

After a few weeks the girl returned to the police with fresh allegations and her mother asked for the case to be reviewed. Eleven months later, in February this year, Le Vell was again arrested and charged. On Tuesday a jury found him not guilty of twelve sexual offences, including five of rape.

Given that the complaint was not made until a year after the alleged offences ceased, there was no physical evidence to incriminate Le Vell. It came down to his word against the girl's. The jury made its choice and Le Vell went not to jail, but to the pub.

He paused on the way to say the obligatory few words to the press and at one point he dared to do the unthinkable – his sister put her arm round him, he looked back at her and he smiled. Until then he had seemed wary, almost diffident, his eyes uncertain. But once he saw he was among friends, he relaxed. Later he relaxed a bit more and was photographed holding a pint and giving the thumbs-up sign.

The vision of a man who had been accused of rape looking not just relieved, but happy, was too much for some. Others had snapped much earlier – when the verdicts were announced. It seemed that for some, any man accused of rape must be guilty.

And even if he wasn't – some seem to think – he should still be convicted so that other, real, rape victims were not deterred from stepping forward. Better that ten/a hundred/a thousand innocent men suffer than one rapist goes unpunished.

One tweeter even suggested – and defended the stance – that men accused of rape should be presumed guilty until they could prove their innocence.

It wasn't only the jury , which included eight women, that got it wrong – it seems. The prosecuting barrister was a bully who tried to undermine the credibility of the accuser and the press coverage was a disgrace, peddling rape myths. (Why do people always peddle rather than perpetuate myths – is there a market price for them?)

The Guardian and the Independent were thought by one blogger to be so culpable that they should publish front-page apologies. Maybe I missed something, but I've gone through both papers' coverage and can see nothing but straight court reporting throughout. Nothing is written that is not attributed to one of those participating in the trial – although it may be the case that the blogger was in court throughout and that there have been sins of omission.

The Daily Mail, on the other hand, once again showed its mastery of producing seemingly balanced coverage while actually weighting it with well-chosen verbs and adjectives. Le Vell was an innocent actor whose life had been hell for two years after being dragged in for questioning and hauled through the courts. Prosecution lawyers tried to portray him as a guilty man. He wastaken apart on the witness stand in an attempt to expose every minor flaw in his character.

His accuser, on the other hand, was a highly emotional teenager who gave evidence from behind a screen and embellished and changed her conflicting story at every turn. She made spurious claims and admissions and has beenexposed to everyone she knows and who matters to her as a liar.

Well, do you know, it is the job of prosecuting lawyers to portray defendants as guilty men, indeed to prove them to be so if they can. (It is also the case that defence lawyers will seek to undermine the credibility of prosecution witnesses – who may sometimes also be the 'victim' of the alleged crime.) Many witnesses, and not only in rape cases, give evidence from behind a screen or even by video link. There is nothing sinister in the fact.

For the most part the Mail's coverage was what you'd expect from the paper, but there was one unforgivable factoid in one piece that should be brought to the Attorney General's attention.

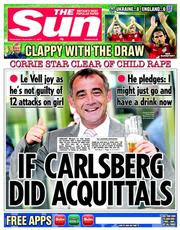

The Sun meanwhile published a front page of such misguided awfulness that it is hardly worth discussing. The 4-5 spread was a run-of-the-mill 'My two years of hell', but then the paper devoted most of 6 and 7 to a making the same points three times – first as 'The weak case against Corrie star', then as a timeline 'How the girl's lies unravelled' and finally as a giant factbox comparing the girl's 'claims' with the 'reality'.

Claim The girl said the sex attacks began when she was six and finished when she was 14.

Reality She did work experience on Coronation Street, aged 15, which Le Vell arranged to help her as she wanted to be an actress.

This might be an unlikely sequence of events, but the 'reality' could equally be a result of the 'claim', an attempt to make amends. Certainly neither one disproves the other.

Back in cyberspace where all men are rapists and all women are moaners, there has been outrage at the assumption that the girl was lying and outrage that she should retain her anonymity.

Some believe that she should now be 'named and shamed' and 'dragged through the courts' on charges of perjury and wasting police time. There is also a revival of the call for rape case defendants to remain anonymous unless or until they are convicted.

There is a problem in this country, as elsewhere, in bringing sex offenders to justice. For many, many years any woman who made allegations of rape or lesser offences were disbelieved by police, subjected to insulting and undignified physical examinations and forced to reveal their life histories in court.

The prevalence of such crimes was therefore unknown. Few came forward to complain, fewer went through with the court case, even fewer saw their attackers convicted and fewer still saw them sent to jail for their crime. Judges were as likely as defence barristers to cast aspersions on the victim's character, morals or behaviour.

Over the years there were half-hearted attempts to improve the situation, but nothing concrete was done until the 1970s. In 1976 the law was changed to allow women complaining of rape lifelong anonymity from the moment they made the allegation – unless they chose to themselves, as the victim of the Ealing Vicarage rape in 1986 did.

The rule was introduced in recognition of the difficulty in persuading women to speak up and of the prolonged humiliation that may follow a trial. As the committee reviewing the law in 1975 said:

While fully appreciating that rape complaints may be unfounded, indeed that the complainant may be malicious or a false witness, we think that the greater public interest lies in not having publicity for the complainant. Nor is it generally the case that the humiliation is anything like as severe in other criminal trials: a reprehensible feature of trials of rape…is that the complainant's prior sexual history…may be brought out in the trial in a way which is rarely so in other criminal trials."

The woman is named in court, but the media are forbidden to publish anything that may lead to her identification. This rule was later reinforced to prevent readers 'joining the dots' by taking different facts from different newspapers to work out who the complainant was.

Say a woman is raped by her brother

One paper might feel that the relationship makes it a better story – especially if most of its readers won't know the man involved – and therefore say that they are siblings without naming either.

Another might feel that it is necessary in the interests of justice to name the accused – and so refrain from mentioning the family link.

While neither paper believes it has done anything wrong, the two reports taken together would lead to the identification of the woman and therefore break the law.

This protection did little, however, to raise the conviction rate and it has taken a long time to reach even its present low level. As it happens, Britain has one of the highest conviction rates in Europe – with 2,333 of 3,692 rape trials (63 per cent) ending in a guilty verdict last year, according to a report from the DPP in April.

But this is a tiny proportion of the 60,000 to 90,000 rapes that are believed to take place each year. Fewer than 16,000 women report attacks to the police, a quarter of the culprits are never identified and even those who are apprehended are most unlikely to end up in court.

Many other statistics were being paraded around yesterday, including a graph on false allegations which actually came from Washington, but even though the numbers differed, they all told basically the same story.

The 1976 Act also gave defendants in rape cases anonymity in the interests of equality and to protect innocent men from lasting stigma. This provision was repealed in 1988 after the Criminal Law Revision Committee concluded that there was no reason to differentiate between someone accused of rape and those accused of any other crime – was there more stigma attached to having been accused of rape than of murder? The committee rejected the notion of equality between the parties as superficial.

There have been a couple of attempts since then to reinstate anonymity for men charged with rape, most particularly to protect teachers and others responsible for children from malicious accusations, but these have come to nought.

This is partly because the number of false rape claims is so low, but also because by identifying a man in custody other victims may come forward.

Today the argument is being rehearsed on the internet, with some men pointing to Le Vell's acquittal as an unanswerable case for equal protection, while radical feminists point to the rarity of false complaints to explain their concern over the Le Vell verdict.

At the same time there is a third group complaining that the case was brought only because of a 'celebrity witch-hunt' that has led to a string of arrests since the Savile revelations and left anyone in the public eye vulnerable to random accusations.

This, ladies and gentlemen, is what happens in a free society: we have the right to argue loudly and fearlessly regardless of whether we know all' some or none of the facts.

And when a jury clears a man because it doesn't believe the young woman who says he raped her?

That is justice.

A few opinions from all sides:

Charity blasts cross-examination, Salford Online

Shockingly low conviction rates, the Independent

Guidelines on prosecuting rape cases, CPS

My Elegant Gathering of White Snows by Louise Pennington

'Not guilty' does not mean she lied

Le Vell's character is stained, Fleet St Fox

Some thoughts on victim blaming and Le Vell by Glosswatch

Dangerous and persistent rape myths, Sian and Crooked Rib

A life ruined v a fate worse than death

Salem comes to Britain, Brendan O'Neill on Spiked

Anonymity for the accused, Ally Fogg

Prosecution by cliche, the Justice Gap

Anonymity for rape accused, Mark George QC

The case for anonymity for men and boys, COWRA

The truth about rape statistics, Angry Harry

#ibelieveher hashtag on Twitter

Read more from SubScribe on her blog here, and follow Gamoldgirl on Twitter here.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog