The House of Lords heard warnings last night that the proposed ‘snooper’s charter’ legislation puts journalists and their sources in danger.

Peers were also told that the Investigatory Powers Bill could be used by the state to turn journalists’ mobile phones into bugs and secretly grab electronic notes and unbroadcast video footage.

Lords from across the political spectrum last night urged the Government to provide protections for journalistic sources across the IP Bill.

The proposed law gives the state widespread access to peoples’ electronic communications and their digital devices.

It has already cleared the House of Commons and was last night debated by the Lords.

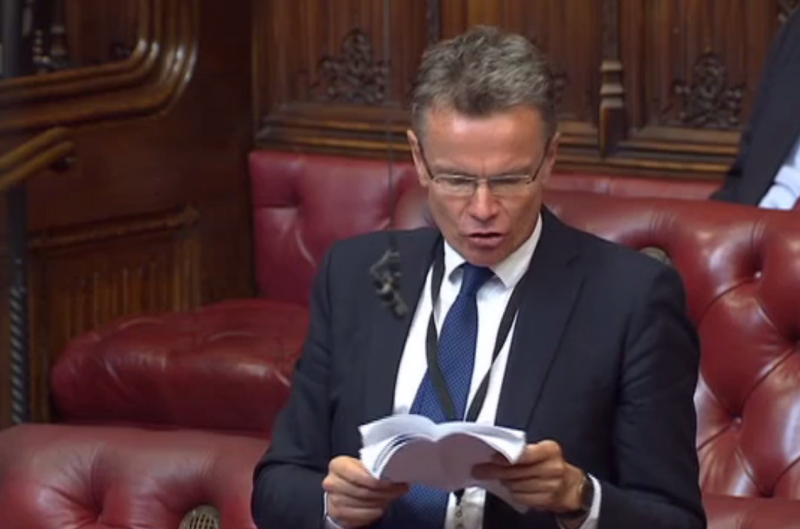

BBC producer and director Lord Colville proposed an amendment which said state requests for journalistic material should have the approval of a judge and that news organisations should be able to represent themselves in court.

At present the Bill only requires judicial approval for telecoms records requests made to identify a journalistic source. It says such applications can be made in secret to telecoms companies.

The amendment had cross-party support and was also backed by the Society of Editors, National Union of Journalists, News Media Association and the Media Lawyers Association.

Viscount Colville warned that “targeted equipment interference” powers set out in the Bill could allow the state to use a journalist’s mobile phone as a “bug”.

He said: “It could also include looking at a journalist’s electronic notebook and at footage shot in the course of a story, which, as a broadcast journalist, worries me a lot.”

He noted that the thresholds for issuing these kinds of warrants include: investigating serious crime, conduct which “involves the use of violence” and “conduct by a large number of persons”.

He said this could therefore cover “the classic case in which the police try to get hold of footage filmed at public demonstrations”.

He said: “I know from experience that journalists are often seen by demonstrators and rioters as extensions of the authorities. This process started abroad, but it is now often seen in this country.

“As a result, we are seeing journalists targeted for taking footage of riots or violent behaviour. This is a dangerous trend, which we should all try to prevent.”

He said this could “increase the risk of violence towards cameramen or their equipment”.

His proposed amendment gave media organisations notice of surveillance warrants “unless there are exceptional circumstances, such as a great emergency or when immediate action has to be taken”.

This would replicate the rules already in place under the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, which covers police requests to view physical journalist material (such as notebooks).

He said: “Mobile phones, computers and the internet are the notepads of the 21st century.”

Conservative Peer Lord Black, who is also executive director of Telegraph Media Group, supported the amendment.

He said: “The protection of sources is crucial for investigative reporting, whistleblowing and indeed free and unfettered political debate. Without adequate protection, investigative journalism becomes almost impossible, whistleblowers do not come forward to the press and wider media to alert them to issues of public interest, and political debate becomes sterile and bland.”

And he urged the Government not to make the same mistakes with the IP Bill as it did with the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act in 2000.

This was the legislation which was widely abused by police in order to allow them to secretly view journalists’ telecoms records in order to identify lawful confidential sources.

He said: “There has been so much attention given in recent years to the way in which sources have been exposed through surveillance and the misuse of anti-terrorist legislation that it is becoming harder and harder to get sources to come forward.

“Some even fear for their lives because they could easily become targets themselves if it became known that they had co-operated with a reporter. It is not an overstatement to say that, on occasion, the protection of sources can be a matter of life and death.

“That is why we must take with the utmost seriousness the passage of any legislation in this House which damages free expression and undermines the protection afforded to confidential sources by opening up the possibility of the state being able to shadow the work of journalists, track what they are up to, identify their sources and see what information they have made available.”

He said there has been “unprecedented co-operation” across the media to seek new protections for sources in the IP Bill.

“The reason for this level of unity is, I am afraid, a profound sense of déjà vu. During the passage of RIPA back in 2000, a similar coalition of interests, led by the Newspaper Society, warned that its wide terms and lack of adequate safeguards would inevitably lead to the undermining of confidentiality of sources…

“The industry was repeatedly told that it was crying wolf and that there was no way the Bill could be so abused. On 6 March 2000, Jack Straw, then Home Secretary in the other place, gave a specific guarantee on that subject.

“But, of course, we know exactly what happened. We have heard of, and seen, numerous examples where local authorities and the police then subsequently used RIPA powers of surveillance to access phone records to crack down on whistleblowers talking confidentially to the press.”

He cited examples where:

- a local authority used RIPA to spy a Derby Telegraph reporter talking to council employees

- Thames Valley police used RIPA to place a bug in the car of Milton Keynes Citizen journalist Sally Murrer and listen to her conversations with a source

- Cleveland police used RIPA in 2012 to access the call records of three Northern Echo journalists to find out who leaked a report about racism at the force.

He said: “It is all very well having judicial safeguards in place, but they will not work unless the judicial commissioner assessing the application has all the relevant information before applying his or her judgment and making an informed decision. After all, how can a judicial commissioner possibly know what they do not know? That is almost Kafkaesque.

“Without input from the media—and I recognise that there must be exceptions to this where a journalist or media organisation is under suspicion—they could not possibly, for instance, know how the use of surveillance could actually place the life of a source, or indeed of a journalist, in danger and other such considerations.”

Former Met Police deputy assistant commissioner Lord Paddick (Lib Dem) agreed that the Bill poses a potential “danger to journalists, particularly camera operators in serious, spontaneous public order situations”.

He said: “This is an area where I have some expertise. At the moment there is a balance as experience has shown that media footage has, in certain circumstances, been useful to demonstrators in terms of misuse or excess use of force by police officers.

“If this were to change, and the demonstrators felt that material gathered by media operators was only under the control of the police because of inadequate provisions in the Bill, this could tip the balance and journalists would become a target for violence in such situations.”

Labour Peer Lord Murphy and the Green Party’s baroness Jones were also among those to speak up in support of the

Lord Howe speaking for the Government rejected the proposed amendment insisting that existing protections for journalists contained in the Bill were sufficient.

He noted that the Government had already changed the Bill to ensure that judicial commissioners consider the overriding public interest before allowing telecoms records requests made to identify a journalistic source.

And he said that an “overarching privacy clause” which requires those carrying out state surveillance to consider the “public interest in the protection of privacy”.

Colville did not push the amendment to a vote, but he urged the Government to “continue discussions with us between now and Report stage”.

Speaking in general about the IP Bill Liberal Democrat Lord Strasburger said: “The surveillance programmes run by our Government now go far beyond anything George Orwell imagined. The more personal data are dredged up and stored, the more the risk of misuse. Now that most of us carry smartphones, government agencies and the police have unprecedented access to location information about where we are 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

“They can also get their hands on all the information on our phones and computers: our contacts, our diaries, our emails, our web browsing, our social networking and everything we do on the internet.”

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog