No matter what their beat, journalists who are reporting day in and day out for newspapers, online, on radio and on TV are regularly working closely with people who are emotionally fragile.

Our current culture is to practise on the grieving public until we reckon we get it about right. We rarely share with each other the skills we acquire or talk about our experiences.

We seem to be the only professionals invited into these homes with no formal training to be there. Dealing with vulnerable contributors is not generally part of student journalism training. It is a risky state of play.

Over the past thirty years I have covered hundreds of people’s sensitive stories as a reporter for newspapers, radio and the BBC.

For the past five years I have researched, crafted and delivered training to hundreds of journalists and students in how to work with emotionally vulnerable people.

I believe we tell our stories best through the people they affect, which is why I put people who chose to speak to journalists at tough times in their lives at the heart of my training.

Grieving families and survivors of sexual abuse – all of whom chose to tell their sensitive stories – spell out constructively what helped and what harmed when working with reporters.

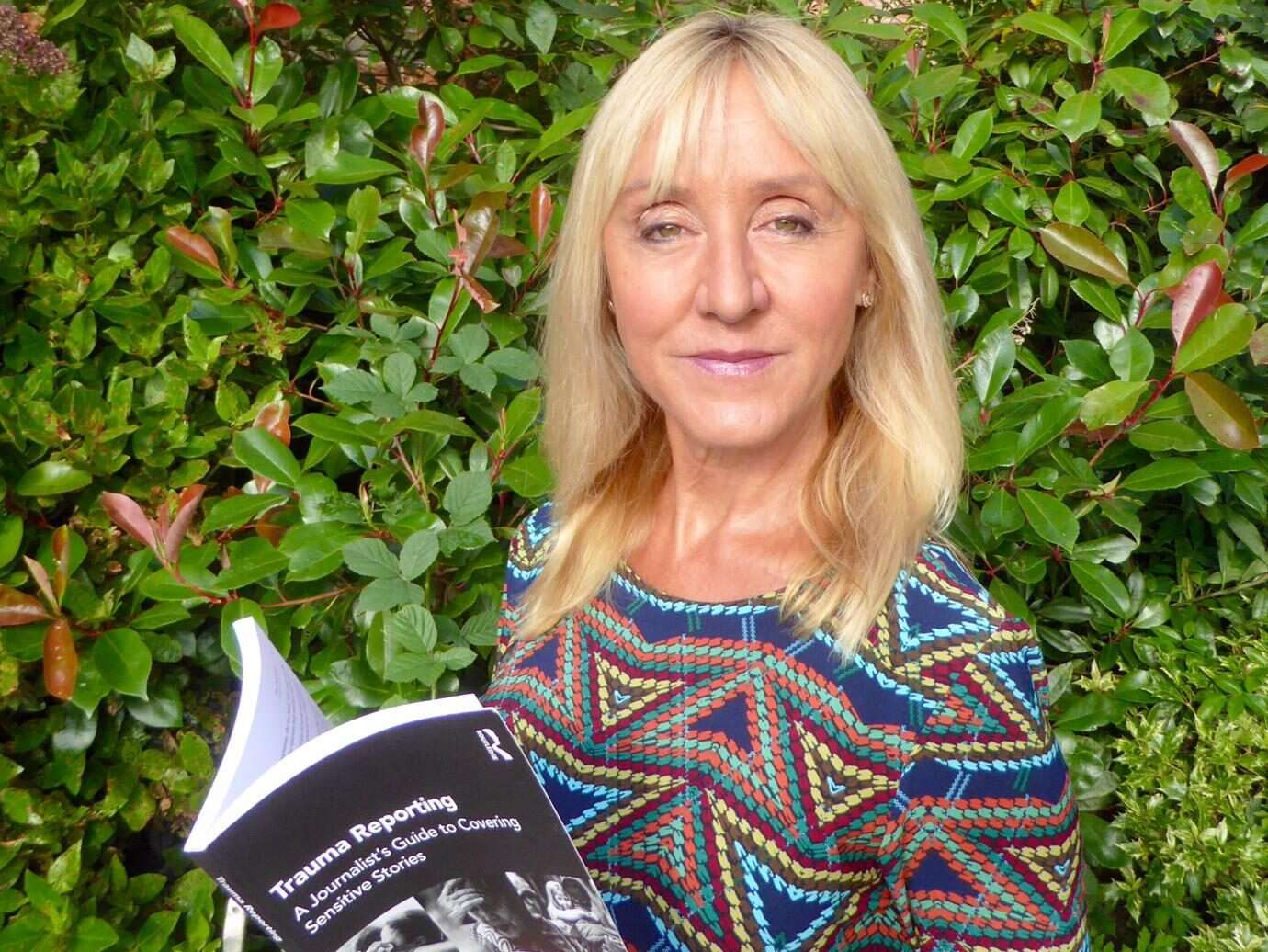

The response has been overwhelming and the feedback from training sessions led to me writing a book on the subject – Trauma Reporting: A Journalist’s Guide to Covering Sensitive Stories.

It follows the process of what we, as reporters, do when a tragic or emotive story breaks and it is our job to work with the people at the heart of it. It applies good practice at each step of the way.

In the book, documentary filmmaker Louis Theroux offers the following advice: “It is absolutely fundamental that journalists treat vulnerable contributors sensitively and with respect.

“In these kinds of stories, you’re talking to decent people who are trying their best to recover from something or deal with something and I think there’s nothing to be gained from upsetting them unnecessarily.

“I do try where possible to extract some positives.”

BBC Paris correspondent Lucy Williamson, who has covered a dozen major terrorist attacks, says her key advice when approaching people at the scene of a traumatic event is to be a human being first.

“No story is worth a person’s mental health or a person’s life, not yours and not theirs either,” she says.

Humility is the key for Helen Long of Reuters, who has reported extensively on the refugee crisis. “It’s a privilege to hear people’s stories and for them to open up and share their pain,” she says. “Never abuse that.”

Richard Bilton tells how, when covering stories on the Grenfell fire, the Orlando shootings, child labour in Brazil and many more for the BBC’s flagship current affairs programme Panorama, he will keep in touch with his interviewees after the broadcast.

“You are doing your job then going home, their lives have been potentially ripped apart,” he explains.

Jina Moore, former East Africa bureau chief at the New York Times, adds: “Journalists should never, ever, make their subjects or sources feel powerless.”

It is fair to say the book has been built on a bedrock of goodwill from the journalism community and from the families and individuals who chose to speak to us at difficult times. They describe what they need from us to be able to share their stories most effectively.

Melody is a survivor of childhood rape who waived her right to anonymity after her stepfather was jailed. She says it is important for reporters to explain and involve interviewees like her in what they are planning to film.

“I definitely needed to know why they were doing it,” she says. “Someone who’s been a victim of abuse, they’ve already had too many people making them do things without explanation and it wasn’t pleasant.”

Anne Eyre is a survivor of the 1989 Hillsborough football stadium disaster and co-founded Disaster Action, representing families involved in nearly thirty disasters worldwide.

“Dealing with personal tragedy is hard enough, but dealing with the media often compounds the pain, trauma and powerlessness of uninvited experiences,” she says. “It doesn’t have to be like that.”

Child Bereavement UK says the way families are treated by the media “can have a massive impact on them”.

Training hundreds of journalists has shown me how many can feel vulnerable when faced with spending time interviewing, filming and writing about people who are suffering.

It is also clear that it matters to them that they don’t exacerbate people’s trauma.

There cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach when dealing with people’s reactions and emotions, but there can be good practice which reporters can adopt, so that they do their job, do it well and do no harm.

Trauma Reporting: A Journalist’s Guide to Covering Sensitive Stories written by Jo Healey and published by Routledge is out now (save 40 per cent with the code TR230 for a limited time).

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog