Whether it was doctors taking us behind the veil of Covid-19 intensive care units or a teenage girl shaping history by filming the horror of George Floyd’s death, user-generated content (UGC) has had a huge impact on news media over the past year.

Lockdown conditions created unimagined restrictions on news reporting but the growing willingness of the public to film and share what they witnessed ensured that hidden stories were still told.

UGC is changing the very practice of journalism and publishers must adapt quickly.

While the infamous ‘pivot to video’ trend of 2015 was premature, and a financial elephant trap for some media outlets, acquiring phone-shot amateur footage is now an essential part of newsgathering as audiences demand real-time evidence of what is reported to them.

The loss of personal connectivity in 2020 generated hunger for the relatable subject matter UGC often provides. Limits on professionally produced content increased the value of amateur content, while Facebook now offers greater scope to monetise it through video advertising. TikTok, with its range of advanced editing tools, is creating a new generation of skilled videographers.

For news professionals, UGC has become an integral element of investigative journalism, of identifying story leads and, above all, reporting breaking stories.

Press Gazette consulted a panel of news industry experts to explore how publishers can best respond to UGC trends to generate the quality content that will give them distinction online, engaging audiences and drawing advertisers from the video-rich social platforms.

Here are their tips:

Focus on medium-form video

News publishers can distinguish themselves from clickbait rivals by moving from short-form 30-90 second clips to quality medium-form pieces of 3-15 minutes with supporting footage and data, argues Jon Cornwell, CEO of the London-based global video agency Newsflare.

“Audience expectations are higher” and there is a demand for greater “context”, he says. “People want to know the prologue to it… what was the consequence and then possibly some statistics to shine a light on a broader issue, whether that’s race relations, climate change or other topics”. Red top websites have trained people in “expecting nothing more” than the “dopamine hit” of a short clip but Netflix binge-viewing habits prove that short attention span is a modern myth, he says.

UGC is powering a different kind of investigative journalism

Bellingcat, the ground-breaking website founded in Leicester and now based in The Hague, was a pioneer of ‘open-source’ UGC investigations, memorably using online imagery to geolocate the Russian-made missile launcher that caused 2014’s MH-17 plane crash.

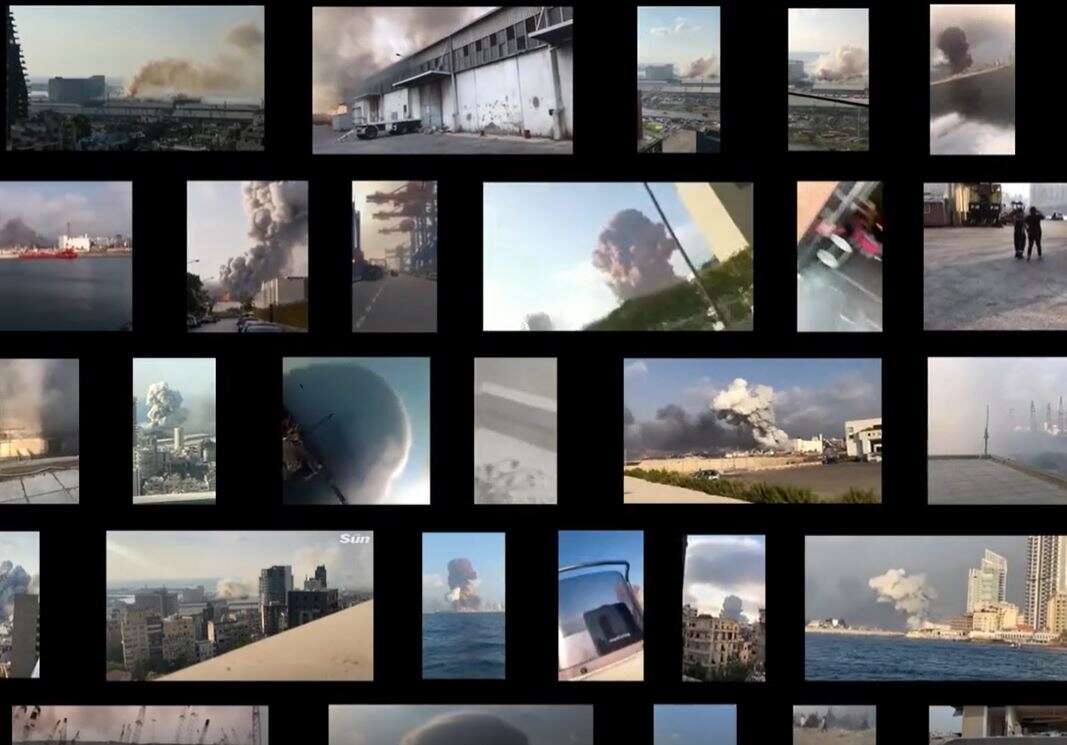

In November, similar techniques were used to stunning effect by the University of London’s Forensic Architecture site to piece together the causes of the Beirut port explosion in August, analysing multiple UGC clips sourced by Newsflare.

Using UGC to report from places journalists cannot go

Under pandemic conditions, news outlets have often found themselves barred from hospitals and care homes, restricting reporting of the most important story of our times.

Fortunately, “there are quite a few very vocal health workers on social media that are sharing information about the situations where they are,” says Steve Jones, social media editor at PA Media, where he leads a team of six monitoring UGC.

“The NHS and other bodies have been quite guarded about letting journalists in. If we try to go through the press offices we are often getting cut off at the pass.”

An online post by a health care worker led PA to the story of London doctors treating Covid patients in ambulances due to a shortage of hospital beds. It made front-page national news.

Testimony is more compelling in UGC

“If we were going through a pandemic in pre-UGC times there would be an awful lot of stuff that we wouldn’t be hearing,” says David Higgerson, chief audience officer at Reach.

“Some of the most powerful [UGC] has been from patients with oxygen masks on, talking from their hospital beds. It’s been empowering for them to get their story out there with the intention of it being seen more widely.”

A first-person narrative is equally valuable for the very different topic of weight loss, a perennial new year story. “We always knew faces sold newspapers, we are now seeing online that being close to the people we are covering is much more engaging than a conventional story.”

[Read more: Taking photos from social media: What news publishers need to know]UGC is news

When Scottish postman Nathan Evans created a viral sensation on TikTok by singing sea shanties, he became news. Jones says PA took the story forward by interviewing Evans on Zoom and profiling a veteran sea shanty group.

UGC as a gateway to stories

Jones says his team acts as “eyes and ears” for PA’s newsroom, using UGC to generate story leads and “filling the gaps where our news reporters and photographers aren’t able to be”. His favourite tool is the Tweetdeck app, using well-chosen word searches (sometimes in multiple languages), as a “net for constantly trawling” the torrent of posts on Twitter.

User video can transform broadcast news

“Televised news in the UK is often like a radio programme,” laments Cornwell. By layering UGC content over dull imagery of correspondents doing “stand-uppers” to camera, TV news could bring new dynamism to the medium, he claims. “There’s no shortage of UGC, it’s just a case of sourcing it rapidly, safely and economically. It’s much more compelling to show images of Brexit’s impact on fishing, rather than have some bloke stood outside Number 10 telling you.”

UGC can provide light on otherwise gloomy topics

The Liverpool Echo scored a lockdown hit with UGC imagery of a doctor running through a snow-covered park in his swimming trunks on a daily stunt to raise money for a hospital. In a previous era, Higgerson notes, the paper “would have sent a reporter to try and talk to him, get the photo and understand what’s going on.” A video shot from distance proved more compelling than a conventional 400-word story.

News brands can use their trusted status to take money back from platforms

Verification is “a business imperative”, says Jones. If PA Media circulates UGC without validating it or clearing copyright, “it really weakens our reputation for being a trusted source”. Higgerson says audiences are less concerned by wonky amateur camerawork than a video’s false provenance. “They take a dim view of us as brands when we find ourselves hood-winked.”

But publishers have everything to gain by becoming the trusted homes of UGC.

Reach recently released research showing that trusted news sites are brand-safe environments even when covering disturbing stories. By bringing added trust to UGC clips in the form of context, Cornwell argues, publishers are simply “returning to a mode they are familiar with, which is telling a whole story, only in video format.”

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog