As a journalist, I had covered the Vietnam War for years and watched as the United States and its few allies stumbled into a foreign quagmire. They could only remove this burden after considerable expenditure of blood and treasure and by abandoning policy objectives. Something similar was about to unfold.

In March 2003, President George W. Bush was hellbent on overthrowing his enemy President Saddam Hussein. I was ensconced in the 18-storey Palestine Hotel opposite Saddam’s palaces across the Tigris River. It had become an unofficial press headquarters and I was told by management that more than 100 journalists had checked in. The Bush White House called on Western journalists to leave the country “for your own safety”.

A similar warning from Bush’s father, then-President George H. Bush, had been directed to reporters who intended to cover the heavy bombing of Baghdad planned for the beginning of Operation Desert Storm in 1991. I stayed, of course, just as I had the previous time when I had conducted the famous, or infamous, interview with Saddam for CNN. I had interviewed him ten days into the first Gulf War in 1991 Desert Storm and was impressed with his military bearing and confident manner.

This time, things were different in several ways. Unlike in 1991, most journalists at the Palestine Hotel opted to remain in Baghdad despite the hotel’s close proximity to Saddam’s palaces which were believed to be the primary target for Bush’s bombs and missiles. Under an arrangement with my production company, I agreed to have my camera crew cover the story for NBC Television news.

NBC News secretly set up local contacts in two buildings near the palaces, ready to provide 24-hour live coverage when the war began and with two cameras in our office suite in the Palestine Hotel, I also had a clear view of the main palace several hundred yards across the Tigris River.

On March 20 at 5:34am, Baghdad time, the military invasion of Iraq began.

I was in my hotel bedroom as NBC anchor Tom Brokaw chatted with me, live, over the audio line. Suddenly, I heard approaching aircraft and the buzz of cruise missiles. My senior cameraman was aiming through the open window when the main palace exploded in a cauldron of bulging, boiling flames.

Kneeling beside my cameraman, the blast pushed me back across the room. I crawled on my belly over to him. He grinned. “Good pictures, huh,” he said. As I peered over the window-sill that was being battered by shrapnel from the bomb blasts, I began counting off the targets for Brokaw’s NBC News audience: Saddam’s palace, his son Uday’s palace, Ba’ath Party Headquarters, Military headquarters. It was ‘Shock and Awe’ indeed.

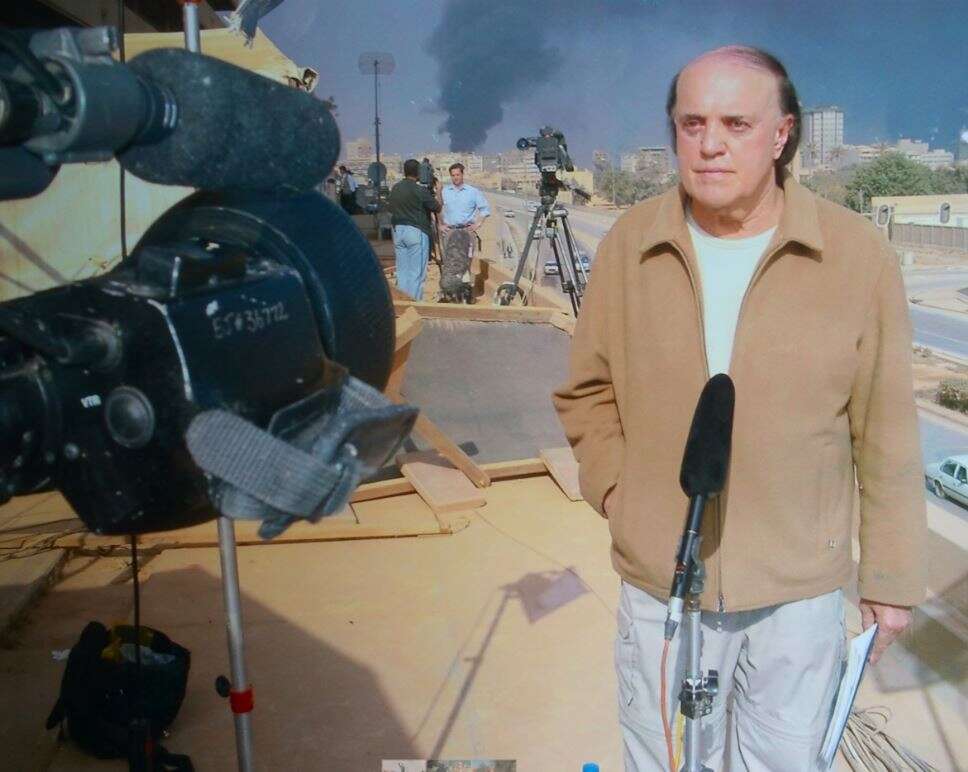

Several days into the invasion American forces were nowhere near Baghdad and we were able to continue broadcasting, alongside several other television stations, from the roof of the hotel.

Eleven days since the war started, a team from Iraqi State Television asked me for my view of how the war was going. I obliged – unfortunately.

At first, I had tried to resist giving an interview to Iraqi TV. When they asked, I told an assistant to Information Minister Mohammed al-Sahaf that I was forbidden to give interviews to government-run news organisations.

He responded: “But we know you have been giving such interviews to visiting crews and television companies run by the governments of Greece, Nationalist China, Jordan, Denmark and Arab states.”

Yes, I told him, but those countries were not enemies of the United States.

He countered: “We invited you here to cover our war. We’ve allowed you and your team great freedom to broadcast around the clock without interference. And we’ve protected you and made it possible to visit contested areas of the city. You say we’re your enemy?

“All true”, I admitted: “Where’s the interview room?”

The setting was a room off the hotel lobby. A well-groomed anchor. Portraits of Saddam on the walls.

I told my interviewer essentially what I had been saying to my NBC audiences, that Saddam’s initial strategy was to mass his conventional forces to slow down a much more powerful attacker, and then relying on his trained insurgents to inflict punishment when coalition forces neared Baghdad. That was happening. I said that the reports of increasing civilian casualties were aiding antiwar supporters in America. I also agreed that our treatment by the Iraqi government since our arrival to report the war had been excellent. I left the interview room wondering who in the world would be watching Iraqi satellite TV.

Well, the AP Cairo bureau was watching. My remarks were transcribed and then sent on the AP’s news services to subscribers around the world.

My remarks led to fury in USA. After all, it was argued, here was a correspondent for American television giving some sort of encouragement to the Iraqi narrative that they were bravely and effectively resisting the invasion. I must say NBC initially kept its cool. The news president, Neal Shapiro, issued a statement that basically said that Arnett was not a regular staffer, but even so NBC did not find anything in the Iraqi interview that required their intervention. Later that day Shapiro phoned me personally to explain: “Fox News has been on your story all day, demanding we fire you. And our affiliates are getting worried. So, I appreciate your work, but we have to let you go.”

So I had been sacked by NBC News – which was rather ironic, since in fact I was not contracted to NBC at all, and NBC was piggy-backing on National Geographic.

National Geographic issued a complaining statement that they had not approved the interview, and ended my agreement with them, neglecting to explain how we happened to be working in the NBC bureau in the first place.

The most cutting criticism came from my old friend and mentor Walter Cronkite whom I had known for 40 years and worked with on issues involving journalist safety and hostage rescue.

He suggested in a column that I was losing my journalistic integrity. I was sorry for my young National Geographic colleagues – three young men and a woman editor – who had been willing to cover a dangerous war zone that their experienced professional colleagues had fled from. They would never get credit for it.

I asked NBC for permission to sign off on the next Today Show and they approved. Matt Lauer was the anchor and he asked me: “Peter, how did this happen? How could you explain it? Too complicated. I apologised that my mistaken judgement had embarrassed the network and probably upset the millions of viewers who had been watching my around-clock coverage of the war for the previous ten days. I thanked Matt Lauer and departed NBC.”

Fortunately, I had another option. Paul Martin, who ran World News & Features, had already contracted me to an Australian independent radio network and he phoned me from Qatar, where he was covering the war. I told him I was downhearted and was planning to leave Baghdad through the desert to the west. No, he said, I’ll find you a good reason to stay. Within hours the Mirror Group of newspapers, which was opposed to the invasion, agreed to sign me up via WNF. The next morning came the famous front-page banner: “Fired by America for telling the truth. Hired by Daily Mirror to carry on telling it.”

I’m very grateful to Piers Morgan, the Mirror editor at the time. I had been handed a journalistic life jacket. So I stayed on, which was one of the best decisions in my career. Inundated with a flood of requests for interviews from television stations and newspapers worldwide, I asked Paul Martin to turn down most of them on my behalf.

My Mirror coverage focused on the increasing dangers in Baghdad for Iraqi citizens and the visiting media as American forces closed in on the airport and outer suburbs.

The Bush Administration was making it publicly clear that it was making the capture of President Saddam Hussein a priority and we were seeing bombings and cruise missile strikes hit ordinary houses in the city where intelligence sources had suggested Saddam was located. Rumours swept the press corps that Saddam himself was leading some of the desperate insurgent attacks against patrolling American armoured vehicles.

The visiting foreign press corps had survived the massive early bombing of Baghdad and as April arrived was able to move fairly freely around the city as a few shops and markets were opening and I visited crowded hospitals. But all that changed on what became our alarming “black Tuesday” on April 8, 2003.

In full view of dozens of journalists watching from their rooms on the upper floors of the Palestine Hotel, US bombers attacked the Baghdad bureau of Al Jazeera, the Qatar satellite TV station bureau just across the Tigris River. Very clear signs reading “Press” covered the building from all sides and on the roof. The office had informed the coalition of its exact coordinates as fighting erupted in the vicinity. Yet a correspondent was killed in the bombing and another wounded. A US Central Command spokesman said that the TV station “was not and has never been a target” even as the US Government had repeatedly criticized Al Jazeera as “endangering the lives of American troops.”

As a further shock on the same day, I watched as a US tank slowly moved across the nearest bridge over the Tigris, stopped and fired a high explosive shell that slammed into a corner room of the Palestine Hotel along the corridor near mine. I reached the room along with many others and found two journalists dead amidst the rubble, Taras Protsyuk of Reuters and Jose Couso of the Spanish network Telecinco. Three other correspondents were wounded.

The US military said the tank commander had mistaken the hotel for another building suspected of harbouring a suspected Iraqi forward artillery observer. The Committee to Protect Journalists later concluded that the attack on the journalists was “not deliberate, but avoidable.”

I personally did not for a moment believe the US military would deliberately target journalists. Even so for me and the 100 other journalists staying at the Palestine Hotel, it reinforced our fears that our lives were still on the line. A Reuters staffer lit a row of candles in the lobby as a memorial, the most we could do at that time.

Baghdad fell to the US military coalition on April 9, 2003, 20 days after the war started. My sense is that the US military had six months to prove to the many Iraqis who welcomed them as liberators that they had not come to stay indefinitely as occupiers. Yet mistakes were quickly made. While Saddam’s conventional military forces were totally routed, insurgents for several days challenged US force supremacy in the capital, and in other cities.

The coalition victory opened up to public scrutiny a cruel regime that had for 24 years concealed its terrible crimes against the population behind fences and secret prisons. In the cellar of the modern multi-story Olympic building in Baghdad where Saddam’s eldest son and brutal heir apparent, Uday Hussein ran his business empire, I saw instruments of medieval-style torture including iron masks of various shapes and sizes and steel instruments that could inflict pain. In the garden was a windowless concrete structure that was said to be Uday’s private prison.

There was worse. The security forces and wardens running the most notorious prison in the country at Abu Ghraib, a small town north of Baghdad, fled in the last days of the war and the many mainly political prisoners held there for years were released. I visited the prison soon afterwards and saw the bloodstained floors of the punishment cells and the interrogation rooms where steel torture instruments were in neat racks along concrete walls. We were guided by a former prisoner who showed us a small room with a hangman’s rope hanging from the ceiling over a square, deep opening carved into the floor. Images of Saddam were posted on banners along corridors and painted in some prison cells.

On the grounds outside I saw a score or more of Iraqi women, some weeping, others with piles of human bones beside them, digging into the soil seeking the remains of family members and relatives believed to have been murdered in the prison and unceremoniously buried in the grounds.

The victorious coalition initially announced it was closing Abu Ghraib permanently, and then, in a Machiavellian decision, reopened the prison under US Army and CIA management committing a series of human rights violations and war crimes against detainees, including physical and sexual abuse, torture, rape and the killing of Manadel al Jamadi. Revealed in April 2004 by CBS News, the incidents caused shock and outrage and were widely condemned within the United States and Internationally.

As a journalist who has covered many wars I was convinced, and remain convinced, that the military invasion of Iraq by the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia and Poland in 2003 was a political blunder of immense proportions. It was made worse by ill-planning, fabricated intelligence and erroneous assumptions by the western leaders who persuaded themselves that an intervention would stabilise the Middle East.

In the summer of 2014, the Islamic State (ISIS) launched a military offensive in northern Iraq and declared a worldwide Islamic caliphate. The Iraq war and its aftermath had changed the balance of power in the region in favour of the United States’ major adversary in the region, Iran.

And this has also affected the way the West has dealt with the Russian invasion of Ukraine. But that, as we say, is another story.

Copyright Peter Arnett/Paul Martin / Correspondent.World

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog