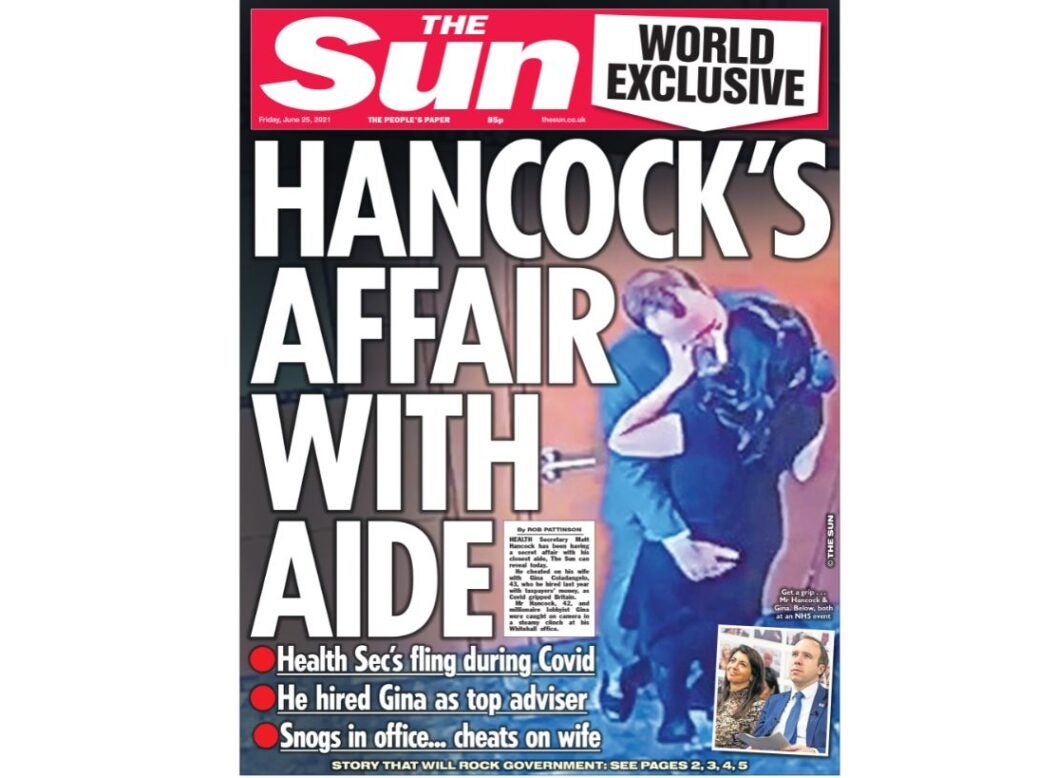

The Sun’s Matt Hancock snogging scoop was sleazy, sensational and in the best tradition of British tabloid journalism.

Awful for the innocent victims involved – the wife, husband and children of Hancock and his mistress Gina Coladangelo.

But it was a breach of privacy that was clearly in the public interest – raising questions around hypocrisy, character, coronavirus rule-breaking and some fairly serious workplace issues.

There are some who would argue that Friday’s Sun front-page story was prurient. Who cares about politicians’ private sex lives?

In this case it would seem that very many voters do care what Matt Hancock has been up to.

And once the video came into the hands of The Sun what else could they do except publish?

When journalists obtain information which is in the public interest they have a duty of disclosure. Given The Sun’s previously fairly supportive coverage of Boris Johnson’s government – it would have been pretty appalling if the paper had not published the story.

Nonetheless, The Sun’s Matt Hancock scoop does raise some fascinating media law issues.

Matt Hancock scoop and media law: Privacy

The initial splash was a clear breach of privacy, intimate activities in a private place, but also clearly in the public interest for the reasons set out above.

But what about the video published late on Friday? I would wager that a judge would consider this gratuitous, now that Hancock has admitted wrongdoing and apologised.

Now Hancock is no longer in the government he may well take legal action to get it withdrawn to save further embarrassment for his wife and children.

When it comes to media scrums around private homes, which again could be upsetting for innocent parties, press regulator IPSO will be stepping in to stop these if there are complaints.

Copyright

The video appears to have been taken on a mobile phone from a CCTV screen. So whoever made that copy would own the copyright. However, the only way to get a copy of the picture and images currently is to copy them from The Sun print edition or website.

It is a grey area, but a potentially costly one. So bigger websites – like Mail Online and the Mirror – have used the picture with credit to The Sun and risked a bill from the syndication department. Small titles, like the local press, have not risked copying the Hancock images.

Bribery Act and Misconduct in Public Office

The source, whoever made the apparent copy of a CCTV footage, faces possible prosecution for Misconduct in Public Office.

More than 30 police officers, prison guards and other public officials were convicted after the Met Police Operation Elveden investigation, which ran from 2011 to 2016 prompted by the disclosure of confidential emails by News Corp in the wake of the hacking scandal.

Any state employee selling a story to a journalist runs a serious risk of imprisonment.

In this case we can only speculate about how the story ended up with The Sun. They say a whistleblower inside the department was the original source. But we don’t know whether the whistleblower leaked it directly to The Sun or, more likely as suggested by this Mail on Sunday story, it went to the paper via an intermediary.

It seems highly likely that if the security services get involved, the original source will be discovered. They should be protected as a whistleblower. But this is by no means a given.

The biggest legal concern for The Sun around the story might be the Bribery Act, which has no public interest defence. This means any direct payment to a government employee for the story would be extremely risky for the journalist concerned.

Some 34 journalists were arrested and/or charged under Operation Elveden for making payments to public officials. Although many went through years of hell, none who denied the charge of conspiracy to commit misconduct in public office were ever convicted. However, these prosecutions pre-dated the Bribery Act which came into force in July 2011.

Protection of sources

Whether a criminal investigation is mounted to find the Hancock video leak source remains to be seen. The Met Police says it is not involved yet, and it may well decide that the public interest would not be served in prosecution, given the public interest in disclosure.

For the government to pursue criminal action against the source might also open up Hancock and Coladangelo to prosecution for breaching coronavirus restrictions.

Nonetheless, The Sun will have needed to exercise extreme caution in this case when dealing with his source.

Press Gazette revealed in 2014 how the Met Police secretly seized journalists’ phone records in order to identify police whistleblowers in the Plebgate case. We also know that the Met has used mobile phone location data to help track down journalists’ sources.

And as Operation Elveden showed, journalists should assume that anything they send or receive on a work email will be handed over to the police on request by their employer.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog