As journalists, we spend our careers searching for words and images to share the stories of strangers with the world. It’s a privileged profession, one where we are able to walk alongside others, often all too briefly.

Our own experiences are seldom comparable with those whose newsworthy stories we share. But our realities and reactions are valid. The nature of our work means we store up experiences and ultimately have our own tales as well. But the idea of a journalist becoming the story, or a journalist sharing their own story is something we are conditioned against.

As the former director of the Ethical Journalism Network, I know this is partly because we are meant to maintain distance from our work, in order to preserve the notion of neutrality or impartiality, as a core principle of our profession.

Ours is an industry where structural inequity means it’s often hard for people to share their difficult experiences because they are worried this might make them seem weak and for those most marginalised by our macho media, it might make them more vulnerable. It’s something I have lived with, though I know I am also privileged to be able to finally speak openly now.

[Read more: Call for journalists to receive ’emotional flak jackets’ against worsening online abuse]

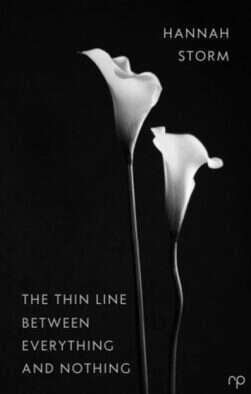

Next week marks the launch of my debut collection of writing – a book of stories inspired and shaped by my journalism experiences, written during my recovery from the post-traumatic stress disorder I developed as a result of my professional and personal life.

Published by Reflex Press, The Thin Line Between Everything and Nothing pays tribute to some of the people and places I have met and been to as a journalist, while allowing me a place to process my own experiences and explore fictional worlds where I imagine what might have been as well as what was.

For 20 years, I travelled the world, working as a journalist, media consultant and in journalism safety, latterly as the director of the International News Safety Institute. During those decades, I lived, worked and journeyed across 60 countries, covering conflict and disaster, meeting inspirational individuals and holding to account others who had abused their positions. Many of the people I spoke with had experienced trauma and tragedy on a scale almost impossible to imagine.

I learned to watch at arm’s length, later to train others to report sensitively, ethically, and safely, even while I saw how I and others within the media industry assimilated and accepted situations which were less than ideal, and were often conditioned towards behaviours that were unhealthy.

For many years, I struggled in silence, suffering the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of trauma connected with my professional and personal life.

Even as the director of a journalism safety charity, I felt unable to really share how I was struggling.

I finally overcame the shame and stigma, sought help, accepted a diagnosis of PTSD and started my recovery. I now speak candidly about my experiences and work with newsrooms to facilitate conversations, where I hope to help others who are struggling to feel less isolated. I also encourage leaders to practice positive role modelling and create safe spaces for all their colleagues, where the taboos of mental health are lessened. I recognise I have a degree of privilege that many of my colleagues do not have.

The past few years have been an intensely tough time for so many in the news media, but in conversations I’ve had and led across the industry, one of the most positive things I’ve found is more people have been sharing their own experiences and their stories. Those connections have created a sense of humanity that I believe is critical to the success of our journalism industry.

The past few years have been an intensely tough time for so many in the news media, but in conversations I’ve had and led across the industry, one of the most positive things I’ve found is more people have been sharing their own experiences and their stories. Those connections have created a sense of humanity that I believe is critical to the success of our journalism industry.

In my book, there are stories where I take my readers behind the headlines, reimagining the worlds that linger long after the cameras and reporters disappear. And because of my personal and professional experiences, I often write about the dynamics that disempower women – inequities that transcend international boundaries.

Much of what I write focusses on liminal moments, hence the book’s title, ‘The Thin Line Between Everything and Nothing’. It explores the fragility and force of human relationships, and the unexpected moments that upend our familiar worlds.

As a journalist I have learned languages which opened windows into worlds different from the one where I grew up. I have met people with perspectives poles apart from my frames of reference. But I have also have learned there are aspects that connect us as human beings.

Whether on a tributary of the Amazon in Peru, a makeshift hospital in earthquake-ravaged Haiti, by Libya’s bullet-ridden Benghazi corniche or on a UK high street, I have seen how love, anger, desire and hope are universal threads. And they have allowed me to shape stories about those threads that we share.

And for me, that’s what journalism and other types of writing really have in common: the ability to tell stories that transcend differences. Far afield, or closer to home, in the newsroom or in our news stories, it’s the ability to make people care.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog