On 19 February 2020, 20-year-old Anisha Vidal-Garner was heading home in the evening. Crossing a road she was hit by a speeding car, which had run through several red lights. She died at the scene.

This tragic and shocking event happened to be captured by the CCTV camera of a local corner-shop. Reporters from Mail Online subsequently bought the footage in order to publish it to millions of readers on its website.

The police pleaded with the newspaper not to publish. The Mail did so anyway. Anisha’s mother, Mandy Garner, was given precisely one hour’s notice that the last moments of her daughter’s life were to be published online as clickbait.

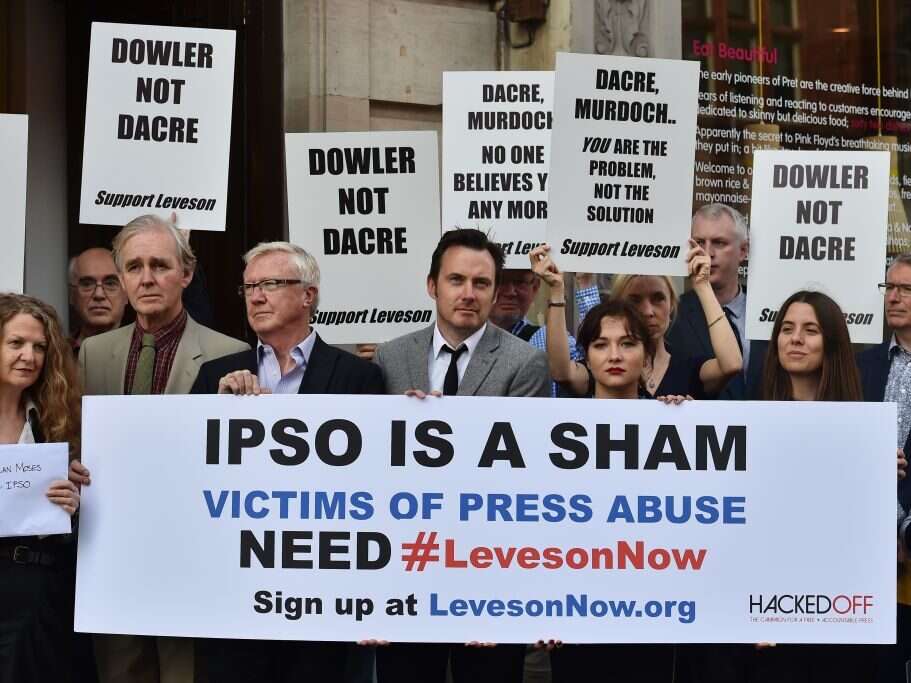

Mandy complained to IPSO, under Clause 4 of the Editors’ Code, intrusion into grief. After several months of correspondence with the Mail, mediated by IPSO, the complaint went before IPSO’s complaints committee. Any ordinary observer would think this was a no-brainer. IPSO decided (full adjudication) that no breach had occurred.

To be clear: it is the view of IPSO that publishing footage of the moments leading to a young woman’s death is not an intrusion into her family’s grief.

This case was uniquely awful. But IPSO’s treatment of Mandy and her complaint was not.

- Litigation not regulation said to be behind press good behaviour ten years after Leveson

- Leveson Report ten years on: News Corp still top for prime minister meetings

- Agency boss: Journalists face ‘endless legals and daily abuse’ post-Leveson

Hacked Off’s research has shown that in 2020, it took IPSO an average of more than five months to process a complaint. Over that time, complainants are expected to engage with pages and pages of correspondence from the publisher. It is no surprise that, in 2020 alone, 1,571 complaints were simply given up on.

Those who were determined to complete this tortuous process were scarcely more successful. In 2020, IPSO upheld only 0.3% of the complaints they received in full. You are more likely to win a prize on the Euromillions lottery.

IPSO may argue that those statistics are likely to include duplicate inaccuracy or discrimination complaints. But even on cases as personal as intrusion into grief, the rate of upheld complaints is below 3%.

Why is IPSO so ineffectual? Because it is effectively a front organisation, with the real power held by the industry it purports to regulate.

Its rules cannot be changed without the agreement of its governing body, the Regulatory Funding Company (RFC), which consists of a group of newspaper executives and a politician.

Its standards are controlled by a sub-committee of the RFC called the Editors’ Code Committee, a body which has a majority of newspaper editors.

So with IPSO, the newspapers aren’t just marking their own homework. They are setting the homework and running the exam boards, too. Little wonder IPSO’s record is so poor.

Take the issue of standards investigations: in its eight years of existence, IPSO has launched precisely zero. And that is not for lack of evidence of wrongdoing.

For example, The Times libelled four Muslims in less than two years; the Telegraph has been responsible for multiple misleading or false claims about climate change and Covid; there have been several other accounts of intrusion into grief apart from Mandy’s. But not a single investigation.

It’s hardly surprising that, of 37 countries in Europe, the UK ranks 32nd for public trust in the press.

As for discrimination, IPSO has not upheld a single complaint of racism or sexism against a national newspaper.

According to IPSO, our national newspapers have not been guilty of a single incident of racist or sexist coverage worthy of an adverse adjudication.

There are plenty of other examples of how, ten years on from Leveson, press standards have not improved – and IPSO’s sorry record is a big part of the problem.

But it is not all bad news: thanks to Leveson, there has been significant progress over the last decade.

Impress, the independent regulator, now has over a hundred members, which is more than IPSO.

Unlike IPSO, Impress has established standards investigations – proactively in at least one case – and even thrown a publisher out of the regulator.

That is what competent regulation looks like.

There is also a growing number of publishers prepared to stand up for press freedom and high standards. Organisations like the Independent Media Association and the Public Interest News Foundation are doing important work advocating for this vibrant part of the news media sector.

But there is still a long way to go.

Impress membership, while growing, tends to attract publishers which have ethical identities and are more likely to abide by high standards regardless of their regulated status, while less responsible publishers, fearing the accountability robust regulation brings, refuse to sign up. As a result, those publishers which need regulation the least are well regulated, and those which need it the most are the least accountable.

Of course many publishers outside the Leveson system – including Press Gazette, for example – produce quality journalism which meets high ethical standards.

But other publishers do not, and the public should – in our view – be entitled to independent adjudication and fair treatment when publishers breach their own standards, as part of a system of regulation which also protects and upholds the freedom of the press.

IPSO fails in two regards. The involvement of the politicians Lord Black on the RFC, Lord Triesman on the IPSO Appointments Panel, and Lord Faulks as the Chair of IPSO, pose a threat to the freedom of the press and risk chilling public interest journalism; particularly that which seeks to scrutinise the governing party of which Lord Black is a member and Lord Faulks a former member.

More dangerously, IPSO also fails to sanction effectively breaches of its own code.

Until all major publishers join an independent regulator, such as Impress, there will be no disincentive for publishers to act unethically.

Ten years on from Leveson, his recommended framework is up and running successfully, with over a hundred publishers now independently regulated. But the national press was always the worst culprit, and their refusal to be part of that framework means that victims of press wrongdoing are no better off than they were under the discredited Press Complaints Commission.

How politicians and governments respond to that failure will be critical in determining whether press standards improve over the next ten years.

[Agency boss: Journalists face ‘endless legals and daily abuse’ post-Leveson]

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog