“We’re not just fighting an epidemic, we’re fighting an infodemic” – World Health Organisation director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

While the entire world descends into lockdown in the battle against the pandemic spread of Covid-19, the news industry, and the sources that supply it have gone into overdrive.

This is happening even in the face of falling ad revenues and the risk of news staff themselves falling victim to the virus.

All over the world media outlets are providing their readers, listeners and viewers with increasingly elaborate updates and advisories about exponential rises in infection and mortality. All happening over the shortest conceivable spans of time.

Add to that the rising tide of comment, anecdote, citizen eyewitness coverage on social media, and you have an expanding information juggernaut that has already grown out beyond the stratosphere.

In the UK many major news outlets have added a coronavirus section to their sites (The Guardian boasts four categories: Corona Virus Live with continuous updates, Corona Virus Explained, for backgrounders, Coronavirus UK and Coronavirus around the World.

The BBC (which also has a Coronavirus tab) has a host of whizzy graphic and visual guides which seek to make the virus and what to do about it accessible and understandable.

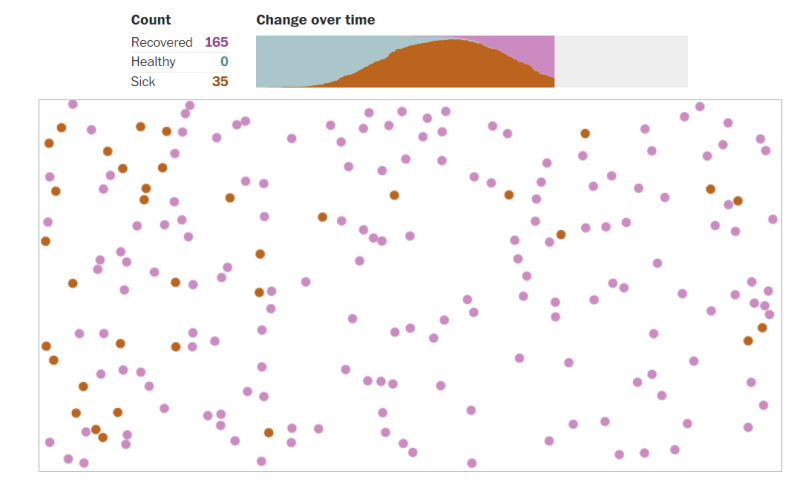

The Washington Post has started a daily coronavirus newsletter with free access to related articles behind their paywall. The paper’s “fake disease” interactive graphic called Simulitis (pictured below), showing the perceived benefit of extensive social distancing, has been widely shared.

A still of the Washington Post’s Stimulitis virus simulator showing the spread of a disease

Unsurprisingly, the industry website Pharmaceutical Technology has a microsite dedicated to Coronavirus. There’s enough here to satisfy all but the most statistically needy Covid-19 obsessive. And there is some reasssurance on offer.

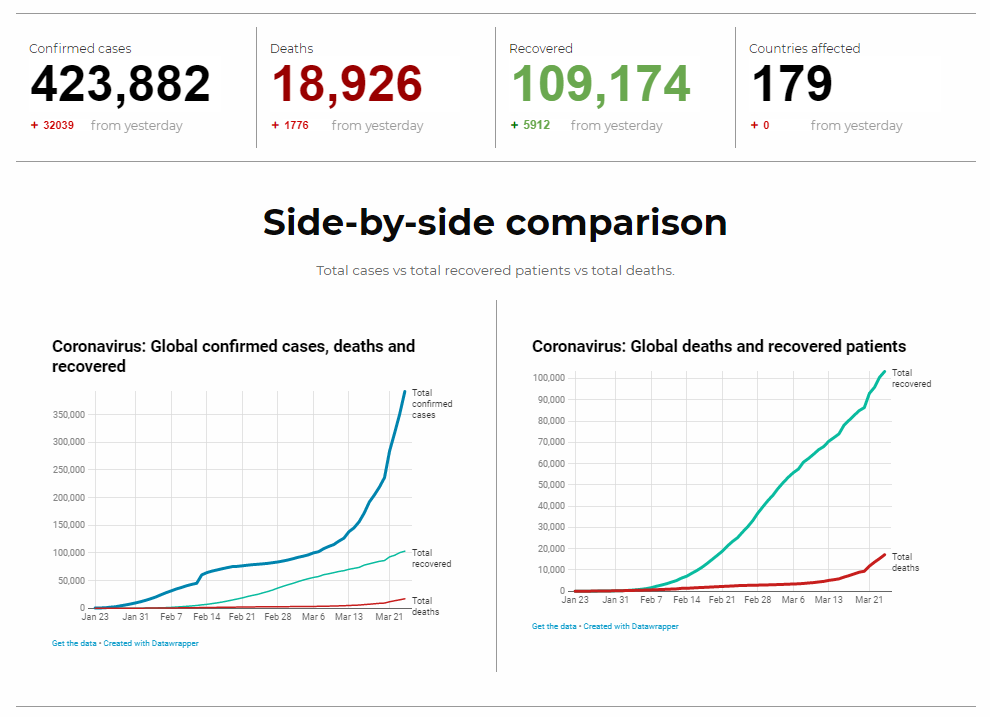

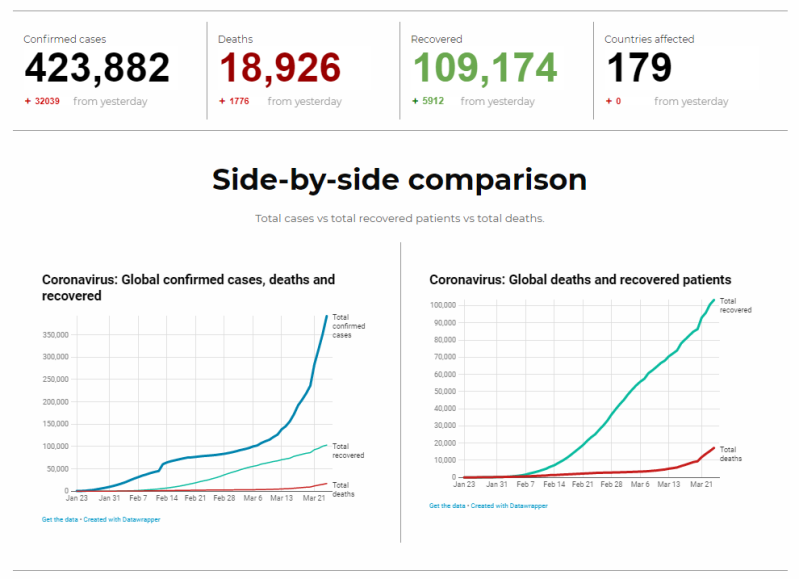

Pharmaceutical Technology’s graph (pictured below) comparing the number of confirmed cases, numbers recovering and total number of deaths shows that although cases are still rising exponentially, so are the number of people recovering, with total deaths producing a much flatter curve than the other two.

Pharmaceutical Technology’s graph comparing coronavirus cases, deaths and recoveries

Italy, the world’s second Corona hotspot after China, has become famous for its spontaneously defiant operatic response to the outbreak.

The popular newspaper Corriere della Serra has a Coronavirus section which leaves the graphs and statistical updates to others so as to concentrate on the human stories and the litany of cancelled (and about to be cancelled) sporting fixtures.

The newspaper is also investigating la app Italiana which allows users to “reconstruct the movements of coronavirus positive people in order to warn others who have been in contact with them… so we can stop the epidemic”’. However, there remain residual concerns about the potential wholesale invasion of privacy that might result in.

Freedom House, the Washington-based democratic think tank reported recently on the Chinese government’s attempts to maintain control over media output and public opinion.

It said: “Of particular concern to government censors has been coverage of Li Wenliang, the Wuhan doctor who along with seven of his colleagues had been disciplined by local authorities for trying to share information about the coronavirus as early as the end of December.

“An article in Beijing Youth Daily about Li falling ill after treating an infected patient was ordered to be deleted by government censors on 28 January. Following the doctor’s death on 7 February, an outpouring of public mourning and anger led to the government issuing censorship instructions to all media, ordering them not to “sensationalize” the topic.’”

Digital posts in support of the campaign #wewantfreespeech, which went viral after Dr Li’s death in February, have also been systematically deleted by the regime.

Using the cover of their arguably swift and impressive battle against the virus, the Chinese government has also increased its surveillance operations over the public, implementing strategies that go beyond any totalitarian fantasy Big Brother could have conjured up in George Orwell’s 1984.

According to Freedom House, in addition to new guidelines issued to criminalise “spreading rumours” about the virus and criticism of the authorities handling of the crisis , the outbreak has been used to introduce even more invasive electronic monitoring systems.These include thermal scanners to identify anyone with a fever in a public place, and phone apps which allow citizens to get a record of their recent travels.

The Close Contact Detector app, created by the State Council, the National Health Commission, and China Electronics Technology Group Corporation, uses information from public authorities and mobile data to alert users if they have been in the vicinity of people suspected to be infected.

Add to this list the introduction of “electronic door seals”, used “to alert authorities if people under quarantine leave their homes”.

The potential to adapt these apps for the purposes of personal and political repression in an authoritarian state like China is not only obvious, but virtually irresistible.

Xinhua, China’s official news agency with scores of correspondents around the world as well as in China relentlessly pursues the regime’s propagandistic agenda.

Although its English edition does not have a separate coronavirus section. Xinhua.net nonetheless features acres of coverage, most of it highlighting what China is doing to battle the virus at home, and helping stricken countries abroad.

At the moment Xinhua is also railing against American attempts to curtail the activities of Chinese journalists working for state-owned or Communist-Party run media in the US. Given the direct connections between agencies like Xinhua and the state and party power structure it is widely suspected that these “journalists” act as agents of Chinese intelligence.

In response, China has recently announced that it will revoke the press accreditation of 13 journalists working for the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post and the New York Times.

This was how Xinhua commented on the dispute: “It is an internationally recognized principle to let media play its role in promoting international cooperation and provide convenience to media outlets for their reporting.

“But the US side, driven by a Cold War mentality and ideological bias, turned a blind eye to this well-accepted practice and restricted Chinese media from carrying out normal operations in the United States, obstructing the free flow of information and undermining press freedom…

“Despite these smears and attacks, Chinese news organisations will continue to stick to the ethics of journalism and follow the principles of truthfulness, accuracy, objectivity and impartiality.”

A search on Xinhua.net for Dr Li Wenliang, (as mentioned, the doctor who was punished by the regime after trying to alert the world to the existence of Covid-19) showed no results.

A simple revelation that casts a long shadow on Xinhua’s avowed dedication to journalistic principles, or perhaps the late Dr Li’s story has simply been lost in the ongoing tide of Covid-19 coverage.

Ted Sullivan is senior lecturer in journalism, (rerited) University of Northampton and editor of “Great Journalistic Investigations and Campaigns”, a recently launched lecture-information programme in support of Reporters without Borders.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog