“Well, we didn’t see that coming.” These must be the hardest words for any futurologist to write and they comprise a pained opening sentence written by Tom Standage, the new editor of the soothsaying magazine produced annually by The Economist.

The past 12 months have been tough for future-gazers.

“As well as causing death and hardship around the world… one of the pandemic’s less important side-effects was to invalidate most predictions for 2020, including our own,” Standage’s article in the newly published The World in 2021 gloomily reflects on the title’s prophesies from the previous year, made just weeks before the emergence of Covid-19.

Serves you right, some might say. If journalism’s role is to produce a “first rough draft of history” then its task is surely to bear witness and to dig out truths – not to stare into a crystal ball and take a stab at what might happen next?

But that rough draft mission statement – ascribed to Washington Post publisher Phil Graham – is too narrow for today’s reporting of a constantly disrupted world, in which audiences now expect publishers, and the analytical writers they employ, to be able to look forward as well as back.

The technological revolution has transformed not only the business model for the news industry but the very definition of journalism. Tech reporting has gone from nerdy specialism to the top of the news list, satiating the public’s appetite for what comes next.

So when it was launched 35 years ago, The World In series was itself a symbol of the future. There was internal pushback when the idea was mooted at an editorial meeting on the 13th floor of The Economist’s old building in St James’s. “We don’t do this, we write about what’s happened, not what’s going to happen,” was the complaint, according to former editor Daniel Franklin.

But the naysayers were quickly overcome and the franchise has grown into a 1m-circulation title (made up of 709,000 in print – including 531,000 to Americans, most of them subscribers – and 270,000 on digital) and has a sister podcast The World Ahead, produced monthly.

Standage, who is deputy editor and head of digital strategy at The Economist, was born to edit “the annual”, as he calls it. As an engineering student at Oxford he dreamed of working in artificial intelligence but, as that sector stalled, he used his understanding of a fledgling internet to get jobs on The Guardian and the Daily Telegraph before joining The Economist in 1998.

“The internet was my ticket into journalism just because I happened to know how to use it,” he says over video link. “I have been trying to find out what the future looks like my whole life.”

On that journey, he has gathered some principles that together comprise a short guide to futurology, as it pertains to journalism. Publishers would do well to take note.

Lesson one: History gives a window on the future

Standage is also a history writer and the author of seven books, in which he looks “to draw analogies between the historical past and something happening today”. The Victorian Internet described how the impact of the telegraph system on 19th Century life was similar to the current online revolution. The Turk told the story of “an automaton that played chess and led to a debate about AI in the 18th Century”. By identifying “patterns in history” we can better predict how society will respond to similar developments.

Lesson two: Don’t be afraid of robots

You might expect an AI-obsessive to say this, but Standage (see Lesson one) has historical evidence to support his case. “This idea that the machines are coming and they are going to take away all our jobs is an old idea and it’s always been wrong; it was wrong in the Industrial Revolution – there were more weavers at the end of the 19th century than at the beginning.” Robots actually create employment, he says.

“If you look at the forecasts of the extent to which jobs are going to be lost to machines, the number has been going down and it’s now finally gone negative. In other words, the consensus is now that automation will create jobs.” The World In used an AI model called GPT-2 for some fun predictions (it successfully called the US election against Trump) and Standage says the new GPT-3 is “even more convincing”.

Lesson three: Live at the edge

Tech journalists “spend their lives looking for edge cases” that are already happening somewhere in the world and offer clues to how we might live in future. He went to Japan in 2001 to see the impact of 3G phones. “What was really exciting wasn’t so much the faster data connection, what was amazing was that they had colour screens, downloadable apps and cameras, and so the Japanese teenagers were living in the future that we all ended up living in.” Today’s edge cases are mostly found in China, he believes. “The business models and apps that Chinese teenagers are adopting now are shaping the world, in the same way that teenagers in 1950s America generated customs, traditions and culture that are still widespread.”

Lesson four: Read sci-fi

“Science fiction is set in the future, but it’s always a commentary on the present,” says Standage, who is currently reading Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future, which depicts eco-terrorists bringing down aeroplanes by the hundred.

Lesson five: No gizmos for their own sake

“The best tech journalism isn’t just about the tech – it’s where tech meets people,” says Standage. “I try to avoid the idea that only new gadgets and gizmos will shape the future.” 5G technology isn’t going to change the world, “it’s just faster 4G”.

[Read more: Expert comment from Press Gazette, including Lionel Barber, Alan Rusbridger and Eleanor Mills]

Lesson six: Avoid groupthink

The World In 2021 includes contributions from writers including Sundar Pichai, chief executive of Alphabet, and the Hong Kong civil rights activist Nathan Law. “The more external voices and contributors we have, the more ideas we have… an interesting smorgasbord of things that might happen.”

Lesson seven: Take a chance

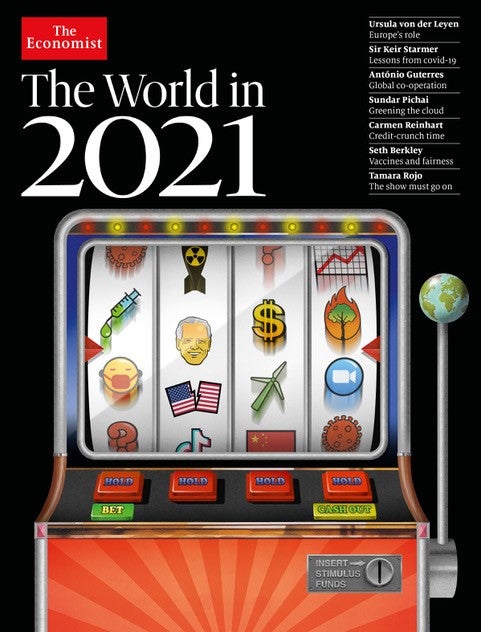

In his editor’s introduction to The World in 2021, Standage notes that 21, a number associated with gambling, seems appropriate for a year shrouded in uncertainty. The annual is designed to give readers information that will improve their odds of future success. But Standage also enjoys taking a punt with some unlikelier speculations in a recurring feature called “What if”, where he moots the idea of Tom Tugendhat as a possible next Prime Minister. “Doing 100 words in a little corner that says it’s just possible this might happen, that’s a fun way of doing it.”

Lesson eight: Know your limitations

The World In’s predictions habitually attract the attention of online conspiracy theorists who believe it is the messaging of a hidden elite who control the world (a The World in 2017 cover depicting protestors in yellow was ‘evidence’ that the subsequent gilets jaunes were pre-ordained). “The conspiracy theorists think we are the Illuminati controlling it all. If that were true – obviously it’s not – then we would do a better job of predicting things,” says Standage. “We are doing the best job we can from the vantage point we have at the end of the previous year.”

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog