Most of us likely have a degree of familiarity with the term “deepfake” – they’ve become increasingly common.

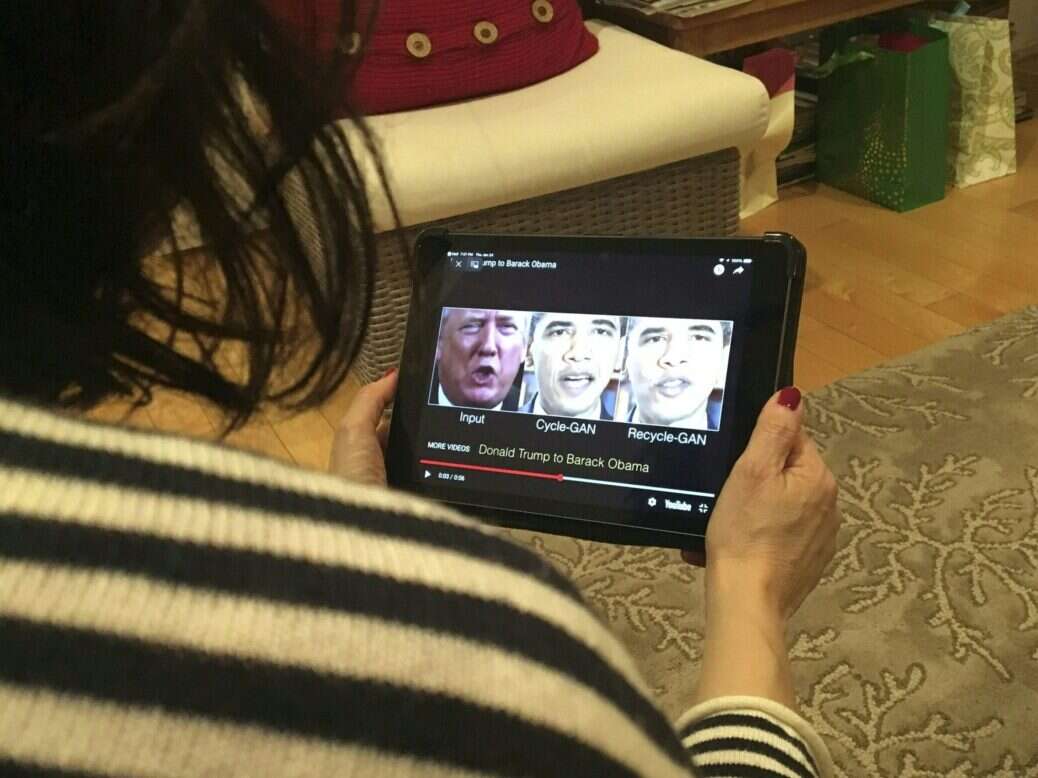

For those who are less familiar, a deepfake is a life-like digital impersonation, usually of a well-known individual. They can take the form of face re-enactment (where software manipulates an individual’s facial features), face generation (where a new face is created), face swapping (where one person’s face is swapped with another’s), and speech synthesis (where voices are re-created).

The metaverse and deepfakes

Given the ability of a deepfake to make it appear as if an individual has acted in a way in which they have not, they pose a direct threat to the accuracy of information relating to any individual in a digital environment.

The advent of the metaverse only serves to increase the risks posed by deepfake technology – there will likely be more opportunities for its use as the metaverse moves from representing individuals as avatars or other similar graphic representations towards representing individuals in more life-like ways.

Time and resource is being poured into the metaverse, and some commentators have predicted that by 2030 we will be spending more time in the metaverse than we are in the real world – shopping, socialising, working and attending events. We are already seeing well-known individuals such as Paris Hilton and Snoop Dogg creating their own virtual worlds, and we should expect more to follow.

Disinformation and manipulation

Many deepfakes we have seen so far have been created as obvious parodies, such as 2020 deepfakes of Richard Nixon announcing the failure of the 1969 Moon landing. However, this evolving technology has the potential to be used for disinformation relating to international diplomacy and even war – in June 2022, it was reported that the mayors of several European capitals had been duped into taking part in video calls with a deepfake of the Mayor of Kyiv, Vitali Klitschko. The pitfalls for journalists here are clear.

It is not difficult to envisage deepfake technology being used by unscrupulous actors to impersonate celebrities and politicians on metaverse platforms and for it to become difficult to distinguish between genuine and fake digital depictions of individuals.

The risk of wrongly ascribing views or actions to individuals is significantly increased in the virtual world, with all of the usual expensive real-world legal consequences. Worryingly, there is also clear potential for individuals to deny past actions and to claim that they have been subjected to the use of deepfake technology.

Trust – a disappearing luxury

So, what can journalists who want to report on what is happening in the metaverse do to protect themselves from libel claims as a result of mistaken identity and make sure they are not being duped?

The same rules are likely to apply to the avatars/graphic representations of people who now appear in the metaverse as will apply once more life-like representations of individuals become prevalent.

The first is to exercise the usual caution when it is not possible to identify conclusively the real person behind the digital representation. If the decision to publish is made, qualify any assumptions as to identity appropriately in any reporting, which may help if an issue does arise.

Another is of course to try to verify the identity of the individual behind the digital representation, via online research or real-life sources. In cases where public interest is involved, the public interest defence may be helpful, provided you reasonably believe that publishing the statement complained of is in the public interest and the reporting is what used to be described by the courts as “responsible journalism”.

In due course it is likely that metaverse platforms will adopt digital identification solutions which will help to verify identity in the metaverse. These will either be developed by the platforms or by third-party providers who may use blockchain technology to verify identity – this is likely to be needed for robust financial systems to develop in the metaverse. Systems such as the blue tick identification already seen on social media may well be used in the case of well-known individuals.

There is also technology in development which aims to discern between deepfakes and genuine footage/content (including AI, which claims to be able to identify audio deepfakes) which may be helpful.

Until then the position is much as it was at the advent of the internet and social media – laws originally intended to deal with the pre-digital world can often be used to deal with issues relating to the metaverse in the same way. If not, the law will eventually catch up either through case law or legislation.

As all the world becomes a stage, the best advice is to be aware of the potential for digital impersonation. Trust has become an unaffordable luxury, so be cautious – check and verify the real person behind a digital representation where you can.

Carolyn Pepper is a partner at Reed Smith LLP. Her co-authors are Jonathan Andrews, associate, and Alex Dainton, seconded trainee.

Picture: Rob Lever/AFP via Getty Images

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog