At the end of July The Guardian, Der Spiegel and the New York Times published investigations based on thousands of secret military documents about the US conduct of the war in Afghanistan released by the website Wikileaks. The news organisations were each given a three-month headstart before Wikileaks released the data to the world.

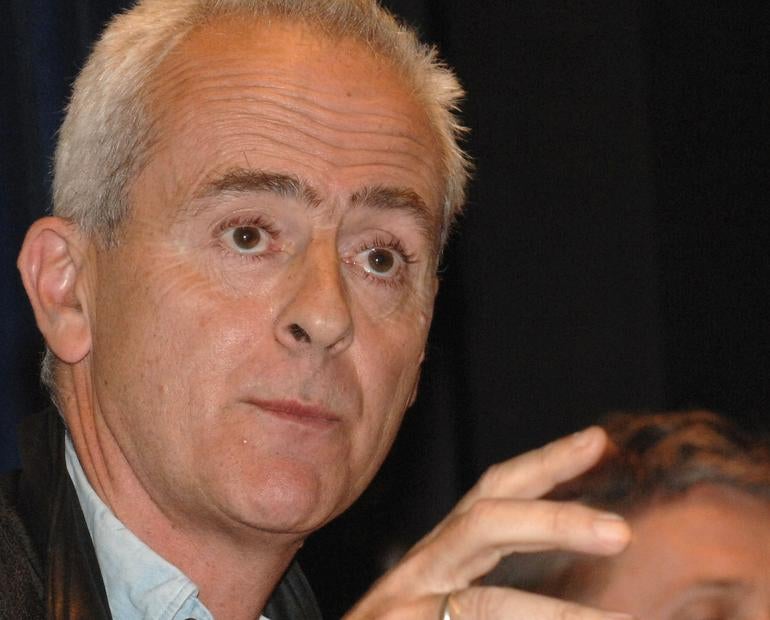

Here The Guardian’s Nick Davies reveals his part in the investigation which resulted in 14 pages of coverage in the print edition and extensive interactive content online.

I’ve worked a lot harder to bring in stories which were much smaller than the Wikileaks Afghan war logs.

It started in mid-June when I read short news stories about the Pentagon running a leaks inquiry into the apparent disclosure to Wikileaks of a mass of secret US material. They had arrested a young intelligence analyst, Bradley Manning, and there was some online coverage of chatlogs in which somebody who may have been Manning talked about the sheer value of the political scandal contained in the disclosures.

So I set out to find Julian Assange, the founder of Wikileaks. He was lying low as a result of various threatening noises coming out of the US. I spent four days talking to people who seemed to be close to him in the hope that they would have some secure means of contacting him. Eventually, one of them called me late on Sunday night, June 20th, to tell me that Assange was going to try to fly into Brussels to keep an appointment to speak at the European Parliament. I called the Guardian’s Brussels correspondent, Ian Traynor, who agreed to try and find him and to persuade him to meet me.

On Tuesday June 22nd, I met Assange in a cafe in Brussels. His opening shot was that he had the entire internal diary of US military activities in Afghanistan for the last six years and that he was preparing to post it on the Wikileaks site. I suggested he would get more impact and also make it politically more difficult for anybody to arrest him or to suppress Wikileaks, if he let the Guardian preview the material in order to find stories which could then be shared with other mainstream news organisations.

We talked for six hours. He described the nature of the material he had. We discussed the lines of attack which Washington might use. He agreed in principle to the idea of the Guardian preview, but since the database was so huge and since we might have only days before somebody tried to stop us, we agreed it was better to bring other news organisations into the preview in order to be able to do the job quicker. I suggested that the New York Times was a natural partner, since it was highly unlikely that the Obama White House would launch any serious attack on them. He suggested Der Spiegel, where he had good contacts.

At the end of the meeting, he agreed to set up an encrypted website on which he would post the Afghan logs. He used the commercial logo on the paper napkin in the cafe to construct a username and password. I headed back to London, with the napkin in my pocket, and briefed the Guardian editor, who called in his counterparts at the NYT and Der Spiegel and set up a research ‘bunker’ in a discreet part of the building. I headed out to Stockholm for a follow-up meeting with Assange, while reporters from all three news organisations sat down together to collaborate on researching the Afghan war logs.

This piece first appeared in the September edition of Press Gazette magazine and is published here as a sample of the content available to subscribers.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog