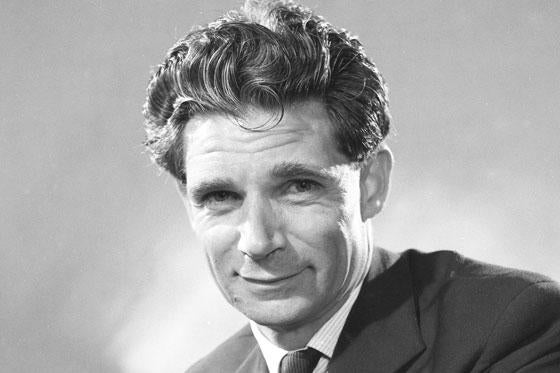

Sir Charles Wheeler – who died at 85 last week after 60 years as a journalist at the BBC – was quite simply ‘the greatest reporter of the television age”, according to former Newsnight editor Richard Tait.

Tait, who edited Newsnight in the mid-Eighties when Wheeler was one of the programme’s main foreign correspondents, said: ‘He had the ability to communicate integrity to the audience. You believed him because he was an honest, rigorous and passionate journalist who loved his profession.

‘Everyone who met him came away with their belief in journalism in some cases restored or reinforced.”

Wheeler joined the BBC in 1947 from the Daily Sketch and continued working for the Corporation until his last days, when he was in a studio working on a Radio 4 documentary despite intermittently needing oxygen.

The programme, due to be aired on Sunday, recalls the Dalai Lama’s flight from Tibet, a story Wheeler covered as South Asia correspondent in 1959. It will feature four other journalists who waited with Wheeler at the foot of the Himalayas for word from the Tibetan uprising.

He had previously covered Germany and eastern Europe during the early days of the Cold War, and later reported from Washington during the Sixties and early Seventies, covering Vietnam and Watergate.

‘That’s why he’s so important – it’s 60 years of reporting,’said Radio 4 controller Mark Damazer, who worked with Wheeler in his first BBC job at the World Service and later, in the mid-Eighties on Newsnight, where they spent five weeks together filming, midwinter, in the Soviet Union.

Exemplar

At the BBC, Wheeler has become an exemplar for the tradition of a field correspondent who gathers first-hand information and then gives viewers the benefit of his judgement and expertise.

‘Nobody, nobody, nobody is above him,’said Damazer. ‘He stands as the single, principal, biggest, greatest embodiment of the importance of the reporter as opposed to any other aspect of broadcast journalism and nobody in the history of broadcasting beats it.”

His death is particularly felt among the generation of journalists, many now in the upper reaches of the BBC’s hierarchy, who had first watched his reports from Washington as children on black and white television and later felt privileged to work with him throughout their own careers.

‘We were all both old enough to know how far back it goes and young enough to have worked with him in his prime of primes,’said Damazer.

‘He connects the point when we were 11 or 12 and didn’t know where we were going with our lives and the point where we are 53 and doing completely different things. He spans us as well. Our cohort has a real sense of loss here that some people might not really grip.”

For many, Wheeler is particularly remembered for his on-air presence, particularly his voice.

Former colleague, Newsnight’s Gavin Esler, said: ‘He always broadcast the way he spoke – he never raised his voice. His voice was very distinctive and very conversational and almost very confiding because it was so quiet. What Charles did was explain very difficult things to people in very simple language.”

Wheeler criticised broadcasters who shouted on television, an approach he associated with drawing attention to the journalist and therefore away from the story itself.

‘He felt they were saying ‘look at me aren’t I important?’Charles was saying ‘listen to me – this story is important. It was completely different,’Esler recalls.

‘That’s why so many people respected him. He always thought the story was important. He didn’t particularly think of himself as particularly important and certainly not self-important in an industry that is often very self-important.”

Esler says an important lesson from Wheeler was that he never assumed viewers or listeners had much background knowledge of the story.

‘He never treated people as anything other than intelligent people who could understand what he was saying without being patronising or condescending,’said Esler. ‘Quite a lot of people could learn from that.

‘He inspired a whole generation of programme makers to do it the right way.”

Former colleagues also recall an extraordinarily gifted television writer who had an apparently innate mastery of the medium’s requirements for combining his narrative with on screen images.

‘He wrote for television better than anyone I have worked with,’said long-time BBC colleague, Tim Gardam, now principle of St Anne’s College, Oxford.

‘He wrote with extraordinary economy and precision. He was a master of clear reportage,’said Gardam, who also admired Wheeler’s ability to shift between hard news reporting and constructing documentaries.

For Gardam, one of the lasting lessons of his collaborations with Wheeler was his ability to resist participating in pack journalism but rather pronounce, fearlessly, his own interpretation of the events he had witnessed.

‘Charles would not be informed by the conventional wisdom of what the story was,’said Gardam. ‘He made judgements with the evidence of his own eyes and listening to people rather than just following the herd of journalists gossiping in the bar in the evening about what they thought the story was.”

Hapless producers

The demand for first-hand evidence of any factual claim also left a lasting impression on those who worked with Wheeler.

‘He was extremely keen on making sure that nothing that he did was even remotely slapdash in any way, or second hand. He was really quite pernickety in that sense,’recalled Vin Ray, now head of the BBC College of Journalism.

‘If he hadn’t found it out himself, then the hapless producer was dispatched to check that it was correct and he would want to know about the sources.”

Though never self-consciously a teacher, Wheeler left a lasting impression on more than one generation of ‘hapless producers’who worked with him.

He was known for a sometimes volcanic temper and impatience with those he felt were not able to meet his high standards or were authority figures obstructing a story.

But his demands for high standards inspired many to do what they consider their best work when they collaborated with him.

Damazer said: ‘However famous he was, however celebrated he was, right until the end if he was with a good production team and he thought you were good he was remarkably selfless and a tremendous team player in terms of making these things happen.”

According to Gardam: ‘He was a very kind man. Charles has a reputation as fierce – and he was fierce as a journalist. When you were working with him as a producer he expected the best, and there were great rows about how a film should go or how a piece should be structured.

‘Charles did always have a rumbustious relationship with his producers. But he did that because he saw the producer absolutely as an equal.

‘When I think about how young and gullible and green I was and how experienced he was, his forbearance and the way he would treat you as an equal and work on the story together was an extraordinary generosity.”

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog