With the Press Complaints Commission set to close down on 8 September to be replaced by the Independent Press Standards Organisation, the time has come for publishers who are still sitting on the fence on the issue of press regulation to make their minds up.

That means chiefly the Lebedev titles and Guardian News and Media. Together they represent three out of the top ten most read UK national newspaper brands.

But there are also an unknown number of smaller publishers who have previously been under the umbrella of the PCC and must decide whether to throw their lot in with IPSO or, like the Financial Times, opt to regulate themselves.

Among those are Press Gazette.

We have not been shy about criticising IPSO.

It was clear that the major problem with the PCC was that it was too closely controlled by the major publishers (specifically News UK, Telegraph Media Group and the Mail titles). When the News of the World hacking scandal began to unfold from 2009 onwards, the PCC appeared to be more concerned with defending the reputation of the industry than with getting to the bottom of the matter.

Despite the first word of its name, IPSO is not fully independent of the press industry. Publishers (via the Regulatory Funding Committee) help appoint the IPSO board and the Complaints Committee and they also convene the Editors’ Code Committee.

The process by which IPSO has been created has been too secretive: with no public consultation, no wider industry involvement (beyond the top executives and editors) and no attempt to meet with the victims of past press excesses to address their concerns.

The importance of press regulation was brought home to me at a practical level last week when we had a rare serious complaint from a reader who felt he had been unfairly treated in a book extract (you can read all about it here).

He was upset about the way he had been portrayed and said he wanted to take the matter to the Press Complaints Commission.

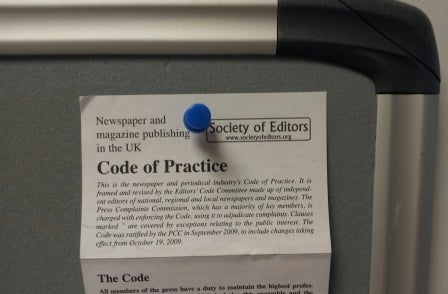

Press Gazette has the Editors’ Code, which underpins the work of the PCC and IPSO, pinned to our notice board. It is a document which emerged unblemished from the Leveson Inquiry as a set of ethical rules which go beyond the law to govern responsible journalism.

If we fall short of living up to that code those who feel they have been wronged should be able to take their grievance to an independent third party.

Not everyone has the means, or the resolve, to engage lawyers. And in any case, not all inaccuracies and mistakes are actionable under the law.

I think it is right that people who feel they have been wronged by journalists should have a “fast, free and fair” way of getting redress (to quote the old catchphrase of the PCC).

Once or twice Press Gazette has been on the receiving end of unfair coverage written on small unregulated news websites. It is intensely frustrating to call the editor of such a site and know that there is little you can do because they are regulated by no-one.

The most harrowing testimony of the Leveson Inquiry came from the Watsons, whose daughter was murdered by another school pupil in 1991 and whose murderer was painted as the victim by articles in the The Herald newspaper. The Watsons’ son killed himself 18 months after his sister’s death, when he was also aged 15, and cuttings from the Herald were found by his body. Their complaints to the newspaper were ignored.

I fear that if more publishers follow the FT and refuse to sign up to any form of third-party regulation they risk allowing this sort of high-handed arrogance to take root again.

Campaign group Hacked Off says that no regulation at all would be better than signing up to imperfect regulator IPSO. I fear they are doing future victims of press excess a disservice by creating more publishers who provide no independent third-party route for the settling of complaints.

The Complaints Committee of IPSO will comprise Sir Alan Moses (a retired appeal court judge whose independence and robustness no-one has doubted) plus six independent members and five industry representatives (not serving editors).

I have no doubt that it will do a good job of fairly interpreting the Editors’ Code (as, in fact, the existing PCC has done).

IPSO also has the power to ensure that the industry deals with cases of major wrongdoing to ensure that we don’t have a repeat of the disaster at the News of the World.

With the UK’s largest Sunday newspaper gone, and 63 journalists arrested and/or charged since April 2011, the consequences of not acting are clear.

The industry has shown its seriousness with the appointment of Sir Alan as IPSO chair and it will be up to him and the other members of his board (six independents and five publishing industry representatives) to ensure that they use their new powers – to launch their own investigations and issue fines of up to £1m – effectively.

We can continue to argue about the finer points of press regulation for years to come, and no doubt we will. But in practical terms I have no doubt that IPSO will provide an effective and fair way of settling complaints that can’t be resolved in-house.

That’s why Press Gazette intends to sign up to it

Update: I may have over-egged the influence of publishers’ body the Regulatory Funding Committee on IPSO. I am told that under IPSO rules its appointments committee must take into account the views of the RFC for appointments which require industry experience, but that it is free to ignore the RFC’s advice. On the issue of lack of consultation over the formation of IPSO, all the major press industry trade associations were involved – with some meetings involving more than 90 people. My point was really that it was devised by publishers without input from ordinary journalists, which it could have sought via bodies like the National Union of Journalists and the Chartered Institute of Journalists.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog