Update 13 May 2024: A feature about Lucy Letby published by The New Yorker in the US has been restricted so it cannot be accessed by readers in the UK.

UK users trying to access the article are met with a message stating: “Oops. Our apologies. This is, almost certainly, not the page you were looking for.”

A New Yorker spokesperson told Press Gazette: “To comply with a court order restricting press coverage of Lucy Letby’s ongoing trial, The New Yorker has limited access to Rachel Aviv’s article for readers in the United Kingdom.”

Letby’s initial trial ended in August last year, when she was also sentenced, but a retrial on one count of attempted murder is expected to begin in June.

She is also currently waiting to find out whether she has been given permission to appeal her convictions. The full details of her Court of Appeal bid cannot currently be reported for legal reasons.

Full story and more information: New Yorker defies contempt risk to publish Lucy Letby story in UK print edition

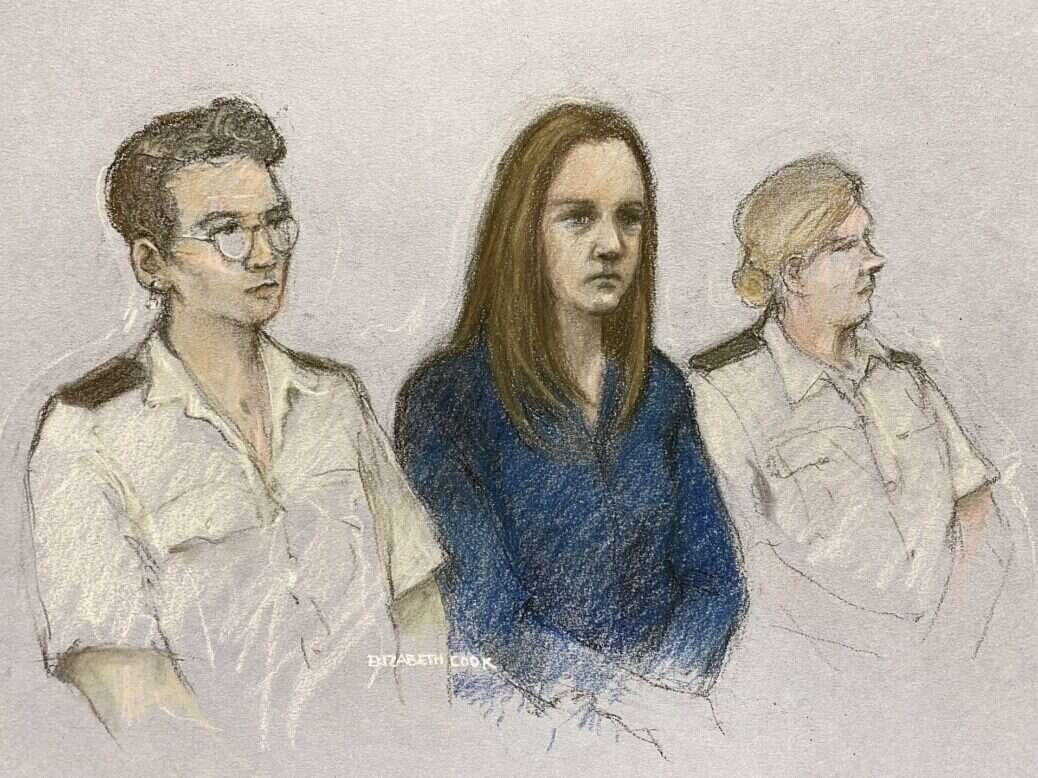

Original story 29 August 2023: Covering the trial of Lucy Letby, the most prolific child serial killer in modern British history, was “incredibly complex” and “so difficult”, journalists who worked on the case have told Press Gazette.

As well as its emotional content, which left some journalists crying at work, the trial was subject to an unusually large number of reporting restrictions.

Some 17 babies and their families, and eight hospital employees, were granted anonymity by judges ahead of the trial, making an already technically complicated case more difficult to coherently explain to readers.

In the UK breaching reporting restrictions, even inadvertently, is considered contempt of court – a potentially imprisonable offence.

One journalist told Press Gazette they worried that if such dense reporting restrictions are granted more often in the future, similarly important cases may become “impossible to follow”.

‘I’m not ashamed to say I cried’

One reporter who was involved in coverage of the entire ten-month trial told Press Gazette “it’s been so difficult”, saying there was “still part of me that finds it quite hard to comprehend – just the sheer evil”.

The journalist asked to remain anonymous, explaining that “however I feel, those families feel 1,000 times worse than I do” and that they did not want to make themselves the story.

The day of the sentencing, when the families made their statements, was one of the hardest to cover, they said, because much of the rest of the trial had been “quite clinical”.

“It’s very easy to shut off the emotional part of your brain and just talk about… key fob entries and all of that kind of evidence, but then when you hear the families talk about the impact of losing their babies and having their children die in their arms…

“I’m not ashamed to say I cried. It’s not the first time I’ve cried covering this case.”

There were times the journalist said they needed to step away “and go to the toilet and cry, or retch, because some of the details were really grim, and the thought that someone could do this to children… I think it’s going to take me a while to process the whole trial.”

Because the verdicts came through “piecemeal” but were only allowed to be reported once all jury deliberations had ended, the reporter said there was a week when they knew “we were in whole life order territory” but they could not “talk to my family and friends about it”.

“And then suddenly it all comes out, and there’s that very intense day, and there’s been a lot of coverage and – yeah, it’s quite surreal now that it’s over. Because it was a long time. And I do wonder, with the jury, how they will assimilate back into normal life, having lived that every day for 10 months.”

Other journalists have similarly described the emotional impact of the trial.

The Guardian’s North of England correspondent Josh Halliday, who was in the courthouse’s media annexe for Letby’s sentencing, posted on X (formerly Twitter) that it had been “the most harrowing two hours I’ve ever spent in a courtroom”.

Daily Mail reporter Liz Hull, who gave birth to her children at the hospital where Letby committed the murders, wrote that she cried in court for the first time in her 25 years as a journalist during the family statements heard in the sentencing hearing.

Meanwhile The Sunday Times’ Northern editor David Collins told Press Gazette the Letby case had been “an incredibly complex trial to report”, both because it was medical and because of the tight reporting restrictions that were put on the media.

“I think that trial was extremely difficult for people to follow. Unless you were there every day and you were part of it, I think, to the average reader, it is really difficult when you’re talking about baby A, B, C, D, E, up to Q, trying to follow which baby is which, what happened when.

“And that’s a really important thing, that, because that plays into the public’s understanding that justice is being done.”

What were the reporting restrictions for the Lucy Letby trial?

As well as the typical court reporting restrictions on publishing anything that may prejudice a jury, journalists covering the Letby case were required to keep an unusually large number of identities secret.

Although anonymity is not usually given to the deceased, all the babies in the case and their families were anonymised, with the children identified as babies A through Q. The BBC’s North of England correspondent Judith Moritz told BBC Radio 4’s The Media Show that the application to anonymise the families had been “fully accepted” by the media, who did not contest it.

However, eight of the medical staff called to be witnesses at the trial also applied for anonymity. Moritz, who was among the journalists covering the case for the BBC, said that “because we were already going to be contending with a case which had 17 babies protected… we had a concern that there would be a practical problem” clearly reporting what was happening.

The BBC, Sky News, ITN, Reach, Mail publisher Associated Newspapers, The Guardian, The Times, The Sun and The Telegraph jointly contested those applications, arguing they conflicted with the principle of open justice, would diminish the case’s transparency and that some of the witnesses had not supported their applications with medical evidence.

However the trial judge, Mr Justice Goss, said he was satisfied that the quality of the witnesses’ evidence “would be diminished by reason of fear or distress” if they were identified, and granted the applications.

‘For me, the bar was not high enough’: Witnesses given anonymity over mental health concerns

Referring to the restrictions, prominent barrister Geoffrey Robertson KC told The Daily Telegraph this week: “Open justice is the most sacred of all British legal traditions, yet in this case it was abandoned because witnesses and victims said they felt discomfort about being identified.”

The Sunday Times’ Collins, who has been covering court for around 16 years, echoed Robertson’s criticism. He told Press Gazette: “I’ve only ever really seen such anonymity used when it comes to evidence being given by people whose lives are at risk.”

He cited as an example the recent trial of Thomas Cashman for the murder in Liverpool of nine year-old Olivia Pratt-Korbel, in which a key witness was granted anonymity because it was believed her life might otherwise be put at risk. Similarly, at the Manchester Arena bombing inquiry, MI5 staff gave testimony from behind screens for reasons of national security.

But Collins said he could not recall any trials at which anonymity had been granted to a witness without either of these reasons.

“There is something called open justice in this country,” he said. “Justice cannot be done behind closed doors. It is an important, if not the most important, part of the process.

“There’s a place for reporting restrictions, of course – when somebody’s life is at risk, or there’s a national security issue I think people would widely accept it. But I think what the big worry is, is that going forward, we have a system that becomes a bit like Germany and countries like that, where – I mean, it’s impossible to follow.” Germany has strict privacy laws and does not generally name suspects before conviction.

Collins said he understood why the families wanted anonymity because of the trauma they had already undergone, the impacts identification might have had on their mental health and because it may have involved revealing their medical information.

“But for me, the bar was not high enough for the witnesses. It is not enough to say that ‘giving evidence would affect my mental health’… At least, you have to be hitting an incredibly high bar there.”

Collins also objected to the idea that “in applying for those [anonymity orders], there was a suggestion that the reporting, if they could be named, would be irresponsible. And that is something that I really didn’t like, because it was kind of tarring the media with the same brush, when actually at the end of this trial, the judge… made a huge point of saying that the reporting of this trial has been completely fair, accurate and really, really good, high quality.”

The journalist with whom Press Gazette spoke anonymously also said they had “never covered a trial before that has had so many reporting restrictions…

“I was surprised at the whole level of anonymity because the orders that were put in place, they’re specifically designed so you can’t give anonymity to someone who has died.

“And also the children’s names have been reported before – the anonymity was only put in place for the trial.”

But they said balancing the principle of open justice against sensitivity for the witnesses was “a really difficult one”.

“I do think that some of the staff would have been just as much victims. And I’m not talking about the hospital management, because I think that’s kind of a separate issue and I think an inquiry will delve into what they knew and all of that.

“But I do think some of the staff who worked with [Letby], who expressed concerns, I do think they are as much victims. And I guess I can kind of see how being associated with this case, having your name in the press next to Letby’s, could be potentially career-destroying.

“So I don’t know if it flies in the face of open justice.” But they added: “I don’t really know why so many staff have been given anonymity, or the consultant she was flirting with.”

What reasons did hospital staff give in applications for anonymity?

The Telegraph reported that one of the staff, whose testimony was attributed in coverage to “Doctor A”, had argued he “suffered from severe anxiety for four years and believed he would struggle to give clear and accurate answers in court if his true identity was revealed”. In addition, his son and daughter were doing their GCSEs and A-levels respectively and had not been aware of his involvement in the case.

One consultant who was granted anonymity said she had struggled with anxiety and depression and that she had lost her own child at the Countess of Chester Hospital, according to The Telegraph. Another consultant told the court she also had a history of anxiety and depression, and that she had previously given evidence in a child homicide case and the process had been traumatising.

A nurse given anonymity had argued it would be difficult to manage her mental health during the trial, and a second said she had been suffering from a low mood since the inquiry started and could need to take time off work if she were named.

This story was updated after publication to make clear that The Guardian’s Josh Halliday was in the courthouse’s media annexe for sentencing, not the courtroom itself.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog