Former Sunday People editor and Mirror Group chairman Ernest Burrington, described as an “outstanding journalist in Fleet Street’s heyday”, has died aged 91.

Burrington, known to friends and family as Ernie, was born on 13 December 1926 in Oldham, the son of Harold and Laura.

Unlike his parents, who were practical people – his mother a mill worker and his father holding a number of labouring jobs as well as that of a security guard – Burrington found his creative spark in the art of writing.

His talent with words soon became apparent and he was encouraged by several teachers who realised his great potential. It wasn’t long before he was sending in stories to his local newspaper, the Oldham Chronicle.

His first breakthrough was a report on a German plane that had crashed in some fields. Its pilot and other crew had hidden in an abandoned barn and Burrington seized the opportunity to make it his first significant article.

He continued to find local stories and get them published using the name of his father, Harold.

On the day he was called to the paper’s office to collect a pay packet the editor handed it to his father who had accompanied him to the Chronicle’s headquarters.

The editor’s expression was one of shock when he was told it was the young boy standing in front of him who had been submitting all the copy.

Burrington showed profound loyalty to where he was raised, not least when he played a major role in the decision to open a printing factory there which meant hundreds of jobs for the local community.

He officially began his career in journalism in 1941 at the Chronicle, which would teach him the basics of how to run a newsroom. He served in the army from 1944 to 1947 before returning to the paper as a sub-editor.

His increasing enthusiasm and outstanding ability to realise how to make a good story into a great one saw him take a post at the Bristol Evening World and then the Daily Herald.

Burrington remained with the Herald as it became The Sun, but moved to the Daily Mirror as assistant editor in 1970. He went on to become deputy editor of the Sunday People in 1971, associate editor the following year and finally editor from 1985 to 1988.

He was called to take on this role again in 1989 for one year.

At a time when journalists still formed the boards of such newspapers, Burrington held a large number of posts within the Mirror Group and was later appointed Chairman.

He then got the opportunity to show off his talents in the US when he was offered a job by Atlantic Media, which meant he was based just outside Miami, Florida, for a number of years.

Alastair Campbell, the political aide and journalist, met him early on in his career when Burrington held the position of editor of the Sunday People.

On hearing of his passing, Campbell said: “My main memory of Ernie is when we were being interviewed for The Mirror training scheme back in 1980.

“We had to be interviewed by all the top brass across the group. When I was with Ernie he asked me what paper I wanted to work for and I have no idea why but I said The Guardian.

“I then spent the next five to ten minutes wondering why on Earth I had said that. First, it wasn’t true and second, I was being interviewed at The Mirror by the editor of The People. After a while I said: ‘Sorry can we wind back. I said The Guardian. I don’t know why, because it’s not true.

“The only paper I want to work at is The Mirror.’ ‘I’m glad you said that,’ he said. I have often wondered whether that swung it for me and whether, if I hadn’t corrected that, I would have made it.”

Burrington had been a close aide to Robert Maxwell and would often tell stories of the erratic behaviours of the newspaper tycoon.

On numerous occasions Burrington was sacked by his boss only to get a call a day or so later from him asking: “Where the hell have you been?” When Burrington would explain he’d been fired, Maxwell would reply along the lines of: “What are you talking about? Get back to the office right now”.

When Maxwell died and his ransacking of Mirror pension funds was discovered, Burrington was criticised as “carrying a limited measure of responsibility”.

There was never a belief or indication he had played any part in the theft of funds and it was later found that Maxwell had bugged his office to ensure he had no knowledge of the criminality which had been taking place.

Burrington informed the police as soon as he suspected the bugging and the devices were removed. Burrington was cleared of any wrongdoing and proved essential to the investigations.

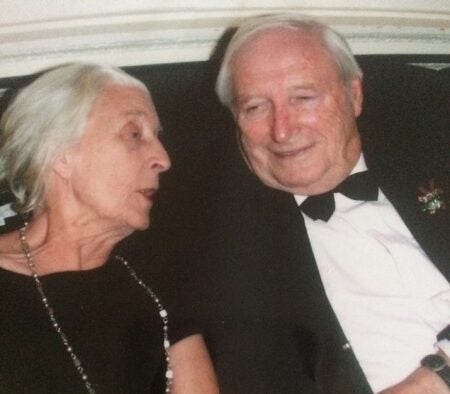

Ernest Burrington and his wife Nancy in 2009

Journalist Liz Hodgkinson said: “I first met Ernie when I was a young journalist on the Sunday People.

“From the start, Ernie encouraged my work and was receptive to my ideas. He was a highly talented, witty, entertaining, imaginative and perceptive journalist and editor, and by sheer brilliance, got to the top.”

“Ernie was never a showy or egotistical editor but quietly got the best out of his staff. He faced some tough times when Robert Maxwell bought Mirror Group News and also when Maxwell died, but coped with typical humour and resilience.

“Ernie was an outstanding journalist in Fleet Street’s heyday and I am so grateful to have had the privilege of working with him.”

In a 2007 Guardian article by Roy Greenslade, headlined: ‘Was journalism better when we boozed’, he reminisces about the days of drink-fuelled mayhem on Fleet Street and cites Burrington’s love and tolerance of the hard stuff as being one such enjoyable spectacle.

He recalled a list of individuals who produced the different shows the combination of a journalist and alcohol could produce. Greenslade included “…marvelling at the drinking capacity of Vic Mayhew or Ernie Burrington” in this piece.

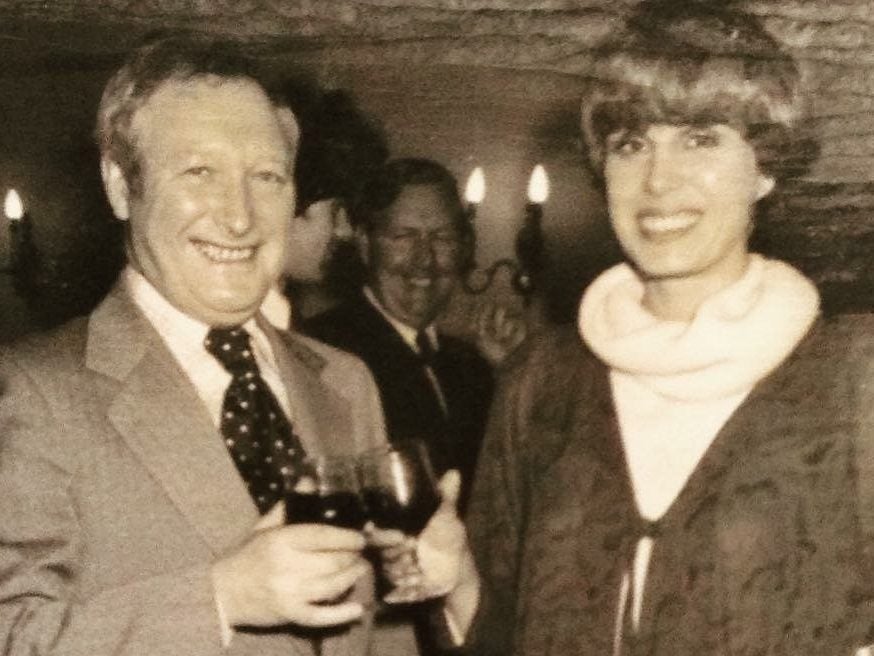

It was a time when many believed alcohol fuelled the creativity which was taking place on Fleet Street and allowed journalists to create bonds with influential individuals (see Burrington with actress Joanna Lumley, pictured top).

However, Burrington’s drinking was said to have been at the stage of nearly costing him his career so towards the end of his years working in the UK he made the decision of adopting at teetotal lifestyle and remained that way until his death.

His political views changed over the years but he was always a great backer of the “underdog” and a champion of opportunity for all. He kept a photograph on his wall, of the first-ever black person who worked in a building in London when he was editor of the Sunday People.

Despite his reputation as being a formidable editor at a time when it’s been suggested tabloid journalism was at its best, I will personally remember my grandfather as a gentle, fun-loving man full of mischief and ideas. If I ever needed guidance or advice he was always only a phone call away.

I know my sisters share the view that some of our greatest family moments would include visits to his and my grandmother’s home in Florida where his energy for days out, card games at home and adventure activities was endless.

Burrington died at home in Tonbridge, Kent on Friday 23 March with his wife Nancy by his side.

He leaves behind a daughter, Jill, daughter-in-law Caroline, five grandchildren – Thomas, Katie, Victoria, Anna and Felicity – and five greatgrandchildren, all of whom will miss him dearly.

His son Peter (husband to Caroline), who was also a journalist, died in December 2008.

A service will be held on Thursday 19 April at 11.30am at St Bartholomew The Great, West Smithfields, London. This will be followed by refreshments at the Punch Pub, Fleet Sreet. Donations to a charity requested, no flowers.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog