Ken Brazier, a former editor of BBC World Service News, who died in August aged 95, knew as a young boy that he wanted to be a journalist.

He left school at 16 to be sure of getting experience on a local paper before being called up for National Service in the Second World War. After the war, he worked for local, provincial, national and overseas newspapers, and the Press Association and then joined the BBC in 1957. There he rose to become Aden correspondent in 1963, covering the insurgency against British rule for four years, and in 1977 he became editor at Bush House.

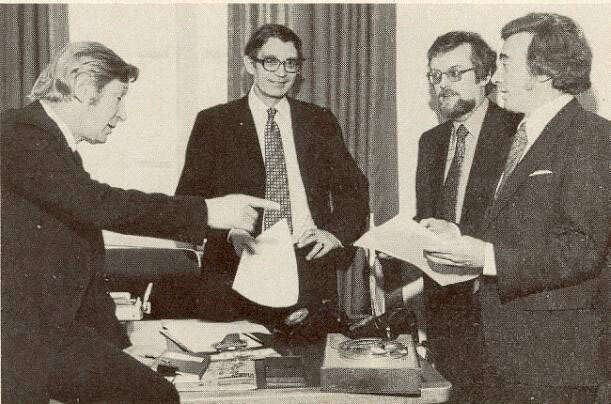

As editor from 1977 to 1984, Ken led the World Service newsroom, one of the biggest and most influential sources of global news, through those Cold War years as Britain sought to establish its post-colonial role in the world. He was an editor of the utmost integrity, unwavering in his defence of editorial independence, freedom of information, and accurate, impartial news reporting. He was greatly respected and liked by his colleagues. “He exemplified the very best of the BBC of those days,” said one tribute from a Bush House colleague.

Ken was born in Ilford, Essex, in 1926, to George and Gladys. His father served as the British civil air attaché in the Middle East in the 1950s. His sister, Jennifer, was born in 1929. War broke out soon after the family moved to a new bungalow, in Ashtead, Surrey. Ken never forgot the horror of watching London burning on the skyline during the Blitz.

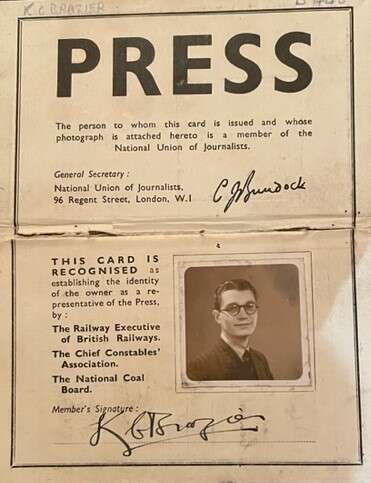

The Epsom Grammar School boy had already started contributing stories to various newspapers when he joined the Croydon Times as a cub reporter in February 1943 and he left school with his headmaster’s blessing. “I have had a chat with Kenneth and am glad to find that this is the kind of thing he wants to do,” he wrote to Ken’s father.

Ken was called up in January 1945 and spent three years in the Forces, first in Bombay and then with the War Graves HQ in Brussels and Paris. His time overseas made a deep and lasting impression on him, firing his interest in the wider world and his lifelong passion for travel. Keen to get back to journalism as soon as possible, he turned down a commission with a place at Sandhurst because it would have delayed his demobilisation.

As soon as he was demobbed in 1948, he returned to the Croydon Times, where he pounded the local beat of crime, court and council reporting for two years, at a starting salary of £4 and 10 shillings a week.

What he always loved was finding the nuggets of news that would make a good story. The National Health Service, then in its infancy, provided plenty of copy: “700 beds were closed, 400 more nurses needed and 2,000 people waiting to enter hospital,” ran one headline. Dentistry was problematic too: “She couldn’t smile with ‘horse fang’ teeth” was another. And there were always neighbour disputes. “Keep snarling over the garden wall” was about a Croydon woman called Ethel who was bound over to keep the peace after coming to blows with her neighbour about a rug hung over the wall.

Ken’s next career move was to the Leicester Evening Mercury, where he became political and city council correspondent. “He was one of the best journalists to pass through our hands since the war,” said the editor in a reference.

He loved his 14 months in Leicester but wanted to get back to London, and he joined the Press Association in Fleet Street as a reporter in 1951.

In 1954, aged 27, and very keen to work overseas again, Ken landed a job on the Bulawayo Chronicle, in Rhodesia, where he was joined by his fiancée, Judy Clement. They were married in Umtali in November 1954 and honeymooned on Paradise Island, off the Portuguese East African coast.

In 1955 they embarked on a huge adventure, driving 2,000 miles from Bulawayo to Nairobi in a second-hand Humber Super Snipe wagon. Towards the end of the trip, they dramatically rolled the car over and were miraculously rescued by people who appeared out of the bush. Ken worked on papers in Nairobi and in Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika.

After returning to London in 1956, Ken worked for the Evening Standard earning £19 a week. They rented a small flat in Red Lion Street, Holborn, above a fishmonger’s who used to supply the hard-up young family with spare kippers at the end of the day, Judy later recalled. Their daughter Mary was born in December 1957, followed by their son Patrick in August 1960. By then they had moved to a brand new three-bedroom house in Crystal Palace.

Ken started his career at the BBC on 15 June 1957 as a sub-editor in the newsroom of External Services (as the World Service was known then), at a starting salary of £1,060 a year.

His big break came in 1963 when he was appointed Aden correspondent to cover the growing insurgency against British colonial rule. It was a massive story, mixing local and regional rebellions against British rule with the wider geopolitics of the Cold War. Britain became embroiled in an escalating and increasingly vicious insurgency by nationalist rebels and finally withdrew in 1967.

On 10 December 1963, a bomb exploded at Aden Airport. Ken was injured by flying shrapnel but calmly filed his story before seeking medical attention, earning accolades and a £50 bonus from the bosses in London for his professionalism. He had been standing near the target of a failed assassination attempt, the British High Commissioner. Fortunately, as he remarked laconically at the end of his cable, he only received light flesh wounds.

Ken always believed that the journalist can never be the story, only an impartial reporter. Two people were killed, and dozens injured, including several other journalists, among whom was his lifelong friend, the Reuters correspondent Ibrahim Noori, who dictated his cable from his hospital bed.

That airport bomb marked the beginning of the four-year Emergency in Aden. In 1967, another bomb came very close to home for Ken and his family when it exploded during a dinner party in the block of flats that they lived in, killing two British women.

A few months after the airport bomb Ken had one of his greatest scoops. He found out about a plane heading for Aden with a macabre cargo and was able to confirm that two SAS paratroopers had been killed by rebel tribesmen in the Radfan mountains, between Aden and Yemen, and their bodies decapitated.

Rumours that they had been beheaded, and their heads paraded on sticks, swirled and were denied, provoking political uproar in London. Ken’s cable was confirmed by a Ministry of Defence statement. The bodies were being flown by the RAF to Aden for burial. The heads had been taken by the rebels to Qataba.

The Aden story was dangerous and complex. The beat included Oman, Sudan, Somalia and Ethiopia, as well as frequent trips upcountry and into neighbouring Yemen, to report on the clashes between rebels and British forces and between the rebels themselves.

The violence in Aden reached a crescendo in 1967, with strikes, street battles and terrorist attacks. A mutiny in June by the British-trained Aden armed police in Crater, at the heart of the insurgency, led to a massacre of British troops. Questions were asked in the House of Commons about the safety of British families. Women and children were evacuated that summer and the British troops withdrew in November, after 128 years of imperial control over what had been a vital strategic asset controlling access to the Red Sea and Middle East oil.

After Ken’s tour of duty in Aden ended, he was sent to cover the Vietnam War for three months, followed by a number of other assignments for the BBC in Beirut, Iran, Cairo and Somalia and then a six-month secondment at BBC TV News.

Bush House was where he felt most at home and after returning there, he became deputy editor of World Service News and then editor from 1977 to 1984. He was respected and admired as a kind and thoughtful editor of the utmost professional and personal integrity.

A former Bush House colleague said in a recent tribute: “He steered one of the most significant and influential – and best – sources of global news through the horrors of the Cold War and the beginnings of our emergence from it.”

Others remember “a great editor”, “a very kind man and a first-class journalist” and “a particularly welcoming and encouraging senior figure … he made a distinctive contribution to why it was such a great place to work.”

With the advent of new technology in the whole of the print and media industry, the big challenge in the Bush House newsroom – where a million words flooded in every day – was to introduce an electronic news distribution system. Ken succeeded in averting a strike by having a typist assigned to type out each journalist’s copy on the new computers.

After retiring from the BBC in 1984, Ken worked as publicity and information officer at the Oman Embassy in London and slowly wound down to full retirement. He then pursued his other great passion, travel, as well as his lifelong interests in photography and carpentry.

He was a skilled craftsman and he made a toy fort and dolls houses – complete with running water and electricity — for his children and grandchildren. He was a devoted family man, who loved being a hands-on grandfather and cared for his wife Judy with the utmost devotion during her long illness until her death in 2018.

During the pandemic lockdowns, Ken kept in touch with family, friends and neighbours by Whatsapp and Zoom and he retained a zest for life right up to the end when he passed away peacefully in his sleep. Newsman to the last, he had been following Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan online that very day.

Kenneth Cuthbert Brazier, born 4 December 1926; died 2 August 2022, was dearly loved and is greatly missed by his daughter Mary, his son Patrick and his three granddaughters Jenny, Claire and Lizzie and all who knew him.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog