In those days it was a rare thing to see a BBC editor not in his suit (and in those days they all seemed to be men).

Rarer still to see one running. Running down a corridor on a quiet Sunday afternoon and tearing into the row of small rooms that was home to Spotlight – BBC Northern Ireland’s current affairs programme.

Wearing – I recall – a tracksuit, sweating and out of breath, Andy Colman, Spotlight editor, could just about get his words out to me between gasps: “Alex – the trail? Where’s the trail? Who’s got the trail?”

And that is when I first knew. The first inkling of a frontal editorial storm incoming: from London, from Downing Street and from who knew where else?

My first job in journalism was as a reporter on Spotlight. Now it occurred to me it could be my last.

One thing was clear. The promo for the coming programme on the Gibraltar shootings was finished, edited – but it was not going to be transmitted, it seemed, as my editor stood in near-panic, demanding to know where the tape of it was.

For weeks we had been investigating the shooting dead of three Provisional IRA members in Gibraltar. Cars hired by the active service unit linked to Mairéad Farrell, Danny McCann and Seán Savage would later be found to contain 132lb of Semtex, wire, tools and a timer.

But when shot dead by the SAS they were unarmed and, said more than one eyewitness, had their hands up in surrender. Moreover, this was at the height of allegations that the British were operating death squads to kill the IRA and ask questions (or not) later.

With our 30-minute documentary ready to go and featuring eyewitnesses and much new evidence of what had happened, we were ready to roll on that sunny Sunday afternoon in Belfast.

It’s hard to exaggerate how charged the atmosphere already was. Thames TV had just broadcast Death on the Rock. There was intense pressure to ban that film. They went ahead.

But Thames TV would lose its franchise a few years later. The struggle to withstand political censorship from the highest level of government proved, shamefully, to be not just editorial but existential for Thames.

Now, with an editor clearly under desperate pressure not to run the TV trail for our coming investigation, the same struggle was coming to the BBC.

We knew by now we had a programme that largely began where the Thames investigation ended and took the story on. Quite by chance, the two programmes dovetailed beautifully. A beauty quite lost on the British government.

As Roger Bolton, editor of the Thames TV film, later wrote: “Relief came from an unexpected quarter … Spotlight fully confirmed what we had reported and went rather further, if anything.”

‘There was not a lot of sleep’

Then, quite simply, the dam burst internally. Endless crisis meetings and memos ensued. Or at least I inferred from the worried looks of men in suits that there was a growing crisis.

I couldn’t quite say for certain because I wasn’t invited to these meetings. That seemed a little odd, as I was the person who had researched and reported, but at the time I was too busy fulfilling endless volleys of requests to check, check and quintuple-check everything in the film and many things that were not. Requests from men much older than I who looked, simply, terrified.

There was not a lot of sleep as we moved towards what would or would not be transmission day – the coming Thursday.

Yet all this time as the hours passed, the wider public knew nothing. That trailer was already banned in an act of internal BBC censorship as the institutional terror set in.

Matters all came to a head when so many men in suits arrived from the BBC in London to view the film that I couldn’t get near the door, still less through it and into the edit suite.

But I do vividly recall the BBC editor in Northern Ireland, John Conway, barking out “New witness! … New point! … New evidence! …” at various points in the film.

If BBC top brass were trying to take the programme down, John Conway, to his eternal credit, was standing by his team and going down fighting.

Would he prevail? In what seemed part internal turf war about London attempting – perhaps – to ban the film and Belfast having none of it, and part the wider confrontation with the government over pressure to censor the BBC, John Conway was fighting Belfast’s corner.

All that week the defence secretary, the foreign secretary and much of the cabinet had insisted broadcasting our film would prejudice any subsequent inquest.

Given no such inquest had yet been convened and that these same cabinet ministers were talking about how the BBC was about to appease terrorists, in parliament and all over the media, this seemed to me a somewhat hypocritical stance.

All the more so for their insistence that the SAS had been right to do what they did. Somehow the coroner wasn’t a problem for them – just for journalism.

But back in the BBC in Belfast matters were not going well. After that viewing there was talk of slashing the film to ten or 15 minutes and having a studio debate to fill the rest of the programme. There was talk of not transmitting it at all.

And I remained largely in the dark as these debates raged up to the director general and back and I was kept well away.

‘I could not have imagined how big the story would get’

So I can now, for the first time in public, break cover. Uncertain that the BBC would not cave in, I leaked whatever I knew of these internal machinations and details of the programme itself to every newspaper I could get to.

If the BBC was going to kowtow to the likes of Geoffrey Howe and other cabinet ministers, I was damned if they’d be able to do it away from the glare of publicity.

The plan was highly effective and it was probably also career suicide (at the BBC). It seems strange now, but I could not have imagined how big the story would then get. Suddenly it was all over the front pages of almost every national paper.

My recollection is that the BBC arranged a hurried screening of the full, uncut film in London for journalists. Excerpts were released and I watched my BBC piece to camera used in the top story on ITN’s News at Ten.

Externally, it had the desired effect – a film quite different from the Thames controversy had now been viewed beyond Belfast whether the BBC desired it or not.

The PR battle all but won, the film was duly broadcast – without trailers – in its planned slot, uncut, uncensored.

Curiously though, the film did not get a wider audience beyond Northern Ireland. As Spotlight reporters, we would routinely re-broadcast our films on Newsnight in those days. But somehow, not this time.

Here was a case for re-broadcasting at its full 30 minutes in a special slot, nationally, after all the days of hoo-hah. The idea of a national newspaper not running an investigation like this from a regional correspondent would be absurd, unimaginable and a blatant act of self-censorship.

But it never happened. I was told at the time by a very senior BBC executive: “Look, you’ve won one battle. Don’t push your luck.”

My abiding impression was of BBC Northern Ireland laudably standing its ground against those from London who appeared minded to do the government’s bidding and censor us.

All of this though, is nothing, nothing at all, set against the period of brutal, up close and personal bloodletting that Gibraltar seemed to somehow unleash. A bleak and dark period of a couple of weeks. It would pass and I would move on.

But where? To my first foreign assignment of my new role at Channel 4 News and back to Gibraltar for the inquest into the shootings. And yes, the inquest passed off with no hint of any prejudice, real or imagined. The judicial system, like journalism, proved a little more robust than the government had fondly imagined.

Alex Thomson is presenter and chief correspondent of Channel 4 News. He previously worked for BBC Northern Ireland.

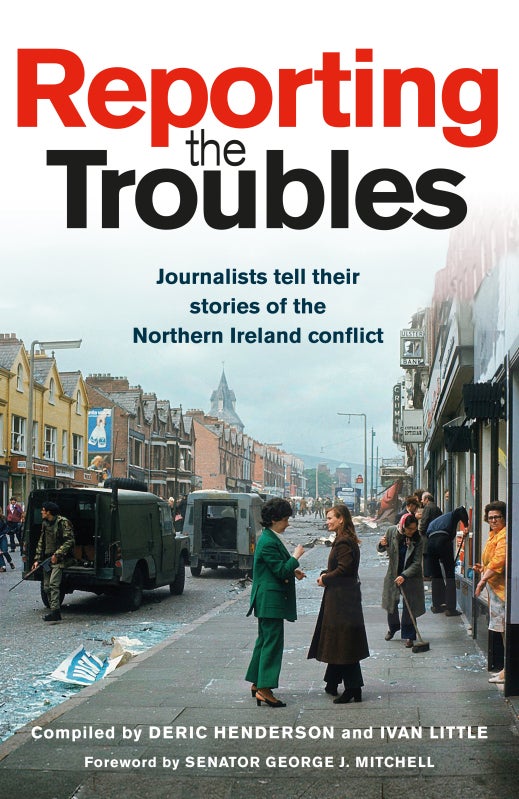

Extract from Reporting the Troubles: Journalists Tell Their Stories of the Northern Ireland Conflict, compiled by Deric Henderson and Ivan Little, published by Blackstaff Press, £14.99, 9781780731797.

Reporting The Troubles, published by Blackstaff Press.

Picture: Channel 4 News/Youtube screenshot

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog