Few would dispute that the police ability to access telecoms data with relative ease is an effective and necessary crime-fighting tool.

But details revealed this week about how this power was used to target journalists in order to find and punish their lawful police sources has shown the extent it has been abused.

The strategy used by the Metropolitan Police when presented with a potentially embarrassing story about the force appears to be as follows:

- Journalists call force with story which may have come from an internal whistleblower

- force press office passes on journalists' mobile numbers to the Directorate of Professional Standards

- police secretly access journalists’ call records in order to identify, punish and shut up the officers who have been speaking out of turn.

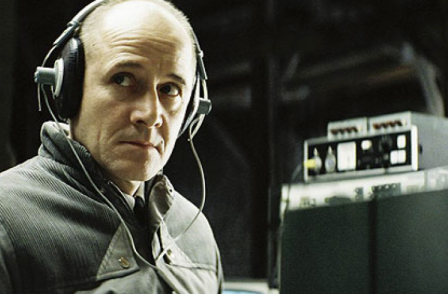

It sounds like a nightmare evocative of Communist East Germany's Stasi secret police, but pinch yourself – because this actually happened in London in 2012 and may be still be going on to this day (albeit with the secret involvement of a judge).

The Investigatory Powers Tribunal this week heard evidence about how the Met accessed the phone records of The Sun and three of its journalists in order to identify the paper's confidential sources.

The facts are as follows:

In September 2012, PC James Glanville called the main Sun newsdesk switchboard with a tip that then Government chief whip Andrew Mitchell had lost his temper with policemen guarding the gates to Number Ten Downing Street and called one of them a “fucking pleb”. Glanville did not witness the incident, but it was the talk of the office and not the first time Mitchell had behaved in a similar way.

Sun political editor Tom Newton Dunn set to work on the story, and colleague Anthony France put in a call to the Met Police press office.

In December, it emerged (thanks to Channel 4 Dispatches) that PC Keith Wallis had lied to his MP about witnessing the Plebgate incident.

Amid claims that police officers were involved in a conspiracy to undermine a government minister, the Met took the decision to access the call records of these two Sun journalists who worked on the original Plebgate story and also those of political correspondent Craig Woodhouse.

The journalists themselves were not under suspicion of breaking the law. But the police secretly helped themselves to a week’s worth data for each reporter, revealing everyone they had spoken to and (via the GPRS information) everywhere they had gone.

The careless way in which the police drove a cart and horses through Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, protecting freedom of expression and journalists’ sources, was illustrated by the slapdash way the telecoms records applications were filled out.

Officers applied (to a superintendent in the same department) to see the phone records of reporter Tom Newton-Dodd [sic] and “political editor” Anthony France.

They obtained the mobile numbers of France and Woodhouse from the Met press office.

This trawl led them to identify Glanville and a second officer who shared information with him. A subsequent secret grab of the Sun newsdesk call records led them to identify another officer who had apparently leaked information about the Plebgate incident.

The Crown Prosecution Service would later decide that all three officers should not face any criminal action because a jury would judge that they acted in the public interest.

But the three were sacked nonetheless.

So the Met Police blew apart long-standing legal precedents guarding journalist-source confidentiality in order to pursue an internal disciplinary matter about unauthorised disclosure of information.

When Andrew Mitchell lost his libel action against The Sun, Mr Justice Mitting said the idea there was a police conspiracy against the MP was "absurd".

Yet still the force argues that this was a proportionate use of powers which were passed by Parliament with the intention of tackling serious crime and terrorism.

As a footnote, it is worth reminding ourselves that the Met also misled us about the extent to which it had monitored journalists’ call records.

The 57-page Operation Alice closing report went into exhaustive detail about how the force left no stone unturned in its efforts to uncover details about the leaking of the Plebgate incident.

Yet the report only mentioned accessing the call records of Tom Newton Dunn and The Sun newsdesk.

In November 2014 Press Gazette asked the Met if had targeted another journalist as part of the Plebgate inquiry.

It said:

We do not routinely confirm the individual cases where we make an application under RIPA.

"As part of Operation Alice the MPS took the unusual step of publicising a summary report of this investigation. That report confirmed where RIPA applications were made to obtain call data from a media organisation.

"Our use of RIPA as part of Operation Alice is outlined in this report."

We now know this was not true.

In March, Parliament changed the law to make it harder for police to help themselves to journalists' call records. Such requests now require external sign-off from a judge.

But the applications can still be made in secret to the telecoms provider with no notice given to the journalist concerned and no one present to make the source confidentiality argument to the judge.

For the sake of all future police whistleblowers the IPT needs to send a message out in its judgment that officers cannot target the phone records of journalists who are not themselves under suspicion of breaking the law without overwhelming public interest justification.

Picture from 2006 film about life in Communist East Germany, The Lives of Others

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog