Journalism in China involves contending with fake roadblocks, undercover cops watching your every move, physical intimidation and the constant threat of deportation.

It sounds like a dystopian nightmare but it is the reality of working life for the Telegraph’s Beijing correspondent Sophia Yan.

The 34-year-old, who turned to journalism after a previous successful career as a concert pianist, spoke to Press Gazette after winning the Marie Colvin prize at the British Journalism Awards for work which included:

- Revealing horrific torture allegations against Chinese secret police

- Reports from Xinjiang, revealing the extent of state repression of the Uighur people

- And the exposure of state-led social engineering that sees Chinese citizens ranked by a social-credit system to regulate their behaviour.

But perhaps most importantly, she was able to travel to the epicentre of the biggest story of a generation. Reporting from Wuhan, Yan exposed the extent of the state-led cover-up in the city where Covid-19 is believed to have emerged.

Yan spoke to Press Gazette via Zoom (which we managed despite the Great Firewall) and I asked her to cast her mind back to early 2020.

“From the very start of the year when news of this strange pneumonia was coming around, for anyone who’s covered China even a little, the first thing you think about was SARS and the cover-up of what happened then,” she said.

“And so there was always a concern and worry about what China was telling the world and how much it was actually divulging – whether it was enough, whether it was accurate.”

While acknowledging that at the start of any new disease outbreak it is difficult for the authorities to track what is going on, she said: “Here, there’s also the issue of a government that doesn’t always want the world to know… It can be a huge challenge and is part of what makes working here interesting but it’s also what makes it so difficult.

“China is not the visible threat of a war zone, but it’s something a lot more sinister that people that I interview or even meet in passing are routinely detained or harassed, interrogated, sometimes even hacked.

“In Wuhan, for instance, government minders assaulted me and they confiscated my devices and they prevented me from working.”

Journalism in China: Fake roadblocks

Other state efforts to hinder journalism border on the comic.

“Sometimes it’s pretty absurd. They’ll throw up these fake roadblocks. I’ve actually seen them set up a roadblock as I’m advancing down the street and of course, when they get there there’s a lame excuse.

“‘Oh, the road conditions are terrible.’ ‘Oh, you can’t go down there, because you’re a foreigner.’ ‘Oh, you’re traveling alone – it’s dangerous.’

“The ways that the government tries to thwart the work of journalists, it’s really incredible.”

Last year China imprisoned 47 journalists. They included Zhang Zhan who sought to tell the world about the outbreak of disease in Wuhan back in February 2020 via Twitter and Youtube. She is being held on charges of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble”.

China is one of the ten of countries in the world which have the worst records on media freedom as identified in Press Gazette’s Media Freedom Health Check published today.

In September last year, two Australian journalists were expelled from China, causing shock even among experienced foreign reporters like Yan.

Yan says: “What was really astonishing for people who’ve been here for a while is they were visited in their homes by state security officers and told that they were banned from leaving China and were part of a national security investigation.

“This set off a diplomatic firestorm and eventually they were able to leave but as more and more foreign journalists are being forced to exit the country it means that it’s even more important for those of us who can stay to continue to shine a light on this country.

“China’s opaque, it’s powerful and it has a huge impact around the world.”

[Read more: Profits from propaganda: Facebook takes China cash to promote Uyghur disinformation]

If China had been a more open society is there a chance the Wuhan coronavirus outbreak could have been contained?

“One of the most interesting things I think that we’ve seen happen this year is that for the first time, the way the government here – the political system, the Chinese Communist Party – is set up has actually had an impact on everybody in the world.

“So the party has local congress officials that work in cities and towns and provinces. And also, of course, the central government. And just like you would have anywhere else, there’s government bureaucracy.

“The issue here is that your next promotion as a Communist Party official is tied to how you perform today. So when local officials in Wuhan first got wind that something was afoot the first instinct is often to just try to figure it out at home without making a bigger problem out of it because that can mean a mark on their record and thus maybe it’s not so great for their career down the road.

“So, for a lot of these local authorities – whether it’s a health commissioner or municipal authorities, in this case hospital officials, and of course city officials – that a lot of it was about trying to see what they had on the ground and to deal with it before reporting it up the chain.

“And so those delays certainly contributed to what the world knew of what was going on at the time.”

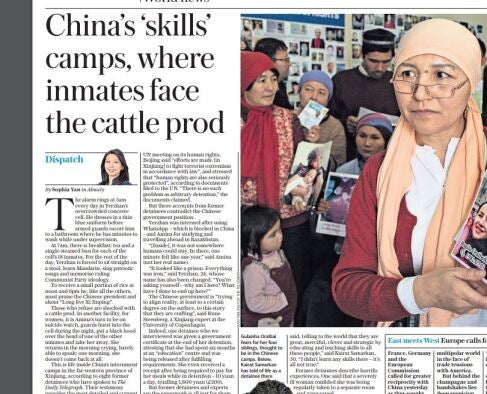

Asked what story Yan is most proud of covering, she cites her work in Xinjiang covering the plight of the Uyghurs.

“Being able to shine a light on that I think has been crucial for how governments are thinking about what this means. What this means for businesses with supply chains. Xinjiang’s a major producer of cotton and now there are all these allegations of forced labour.

“I’ve been really glad that my reports have been able to contribute to wider understanding of what’s going on.”

She also cites her interview with Simon Cheng, the UK Hong Kong consulate worker who was tortured by China’s secret police.

“There was a big concern about his security in the process of communicating with him. I deal with this on a daily basis with just about anyone I want to do a story about.

“With his case, I think it pushed the UK really to acknowledge what had happened. Until that story became public, the UK government at the time hadn’t said anything about it, nor had they told their locally-engaged staff in similar positions what had happened, and that’s a huge risk for people in the jobs.

“That was really something that I thought, you know, this is something that the world needs to know.”

How bad was it really during the early stages of the pandemic in China? Does she think the Covid outbreak was worse than official figures suggest?

“I’ve done reporting that does indicate a lot of cases, a lot of deaths, were not included in the official count. There were tons of people who were dying in the hallways in hospitals all over the place. A lot of bodies weren’t included in those numbers and so I think we may never know the full scale of the impact of the coronavirus here.

“It is true that very severe lockdowns helped in terms of curbing the spread.”

She adds: “Perhaps Beijing doesn’t even know the full scale of what happened. They were so quick to burn a lot of these bodies. I interviewed some crematorium workers. I mean, they were just running this furnace 24 hours a day. So if there was a way to count, it’s not there anymore.”

Yan operates from an office in Beijing, which still carries the brass nameplate, “Daily Telegraph Peking Bureau”, and she is assisted by one researcher.

‘It’s not pleasant, being pushed like that, it never feels good.’

I ask her to provide more details of the physical intimidation she has suffered at the hands of the Chinese state.

“It’s happened a few times on different stories usually near sensitive areas. For instance, I was by a concentration camp site in Xinjiang, one of these detention camps, and there were… six or seven or eight men. I was with a photographer, so we were two women.

“We were trying to take pictures. Trying to go down the street. They had thrown up one of these fake roadblocks saying that we couldn’t go down any further for some completely unspecified reason and we were trying to get further down to get a sense of the scale of the detention centre.

“And so they just they get really handsy. They push you, they grab you. I’ve been grabbed from behind and pulled backwards.”

Yan received similar treatment visiting a cemetery outside of Wuhan.

“Families weren’t allowed to grieve their loved ones who had died from the coronavirus because the Communist Party is always so afraid of people gathering in groups, especially if they’re upset about something, they’re worried about the social unrest and the sort of instability that might come from something like that.

“I was able to go in. I mean, it’s a public cemetery, people can walk in, but it was on the way out that I was stopped.

“And that time, I think there were probably 12, maybe more. They just came out from nowhere. They grabbed my phone out of my hand. When I tried to make a call, just trying to take pictures of who they were, they give me a lot of trouble.

“I am ethnically Asian so they often say, ‘Oh, you’re not a foreign journalist and you’re one of us, and you should know better.’

“It’s not pleasant, and being pushed like that, it never feels good.

“Other times I have been followed by unmarked cars. Sometimes they just watch and follow you around. I joke, perhaps a little bit off colour, that it must be what it’s like to be a celebrity.

“The best I think was once in the Urumqi airport in Xinjiang. There were these two men who had followed me around an airport while I was on a layover and they both had these sunglasses and one of them, while he was watching what I was doing, had a map upside down.”

If Yan was treated this way in her native US or the UK it would be a national scandal. But in China she has to shrug it off as the price she pays for bearing witness to one of the most important stories in the world.

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog