If the decline of the UK regional press since 2008 instead had happened to schools, police, fire stations or hospitals there would rightly be national outrage bordering on revolt.

But the filleting of journalism at a local level has been met largely with a shrug of the shoulders and an acceptance that misinformation, hate-speech and vitriol-filled Facebook posts will just have to fill the gap.

It’s a tragedy because journalism is just as important as those other emergency services. It keeps them in check and does a whole lot more besides.

But post the hacking scandal of 2009-2011 and in the face of a vocal #scummedia lobby on Twitter this is a tough case to make with much of the wider public.

We’ve yet to properly track the decline of local newspapers in the UK. Counting titles only gets you so far because many mastheads continue with a fraction of the reporting staff they once had.

Between 2005 and 2020 we know there was a net loss of at least 265 local newspaper titles in the UK, according to Press Gazette’s tally.

Pre-2007 the Newspaper Society used to boast about the number of journalists its local newspaper publisher members employed. The last time they did that, in 2007, it was 13,000. Not every publisher was a member of the NS, so the true figure would have been higher. Today I suspect we are at around a third of that total.

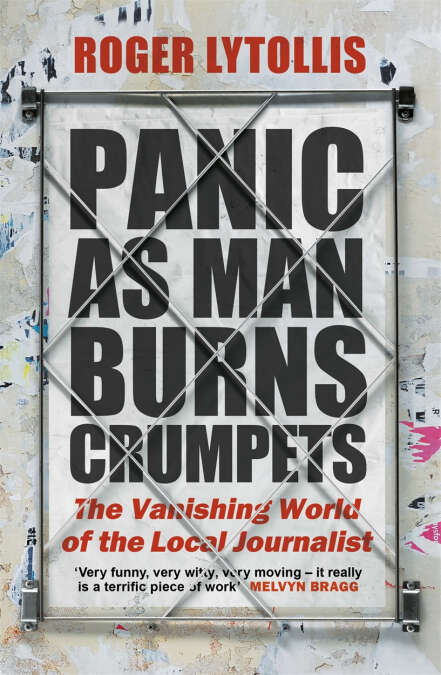

To tell the story of the decline of this industry we rely largely on anecdotal evidence, and there is none better than the equally hilarious and heartbreaking memoir of award-winning local press feature writer Roger Lytollis: Panic As Man Burns Crumpets.

His recently published book provides a fascinating insider account of what happened to family-owned CN Group when it was bought by US-owned media conglomerate Newsquest in 2018 (and of how things were already going sharply downhill before then).

The image that springs to mind to illustrate the Newsquest purchase of CN Group is of a 300-pound gorilla taking ownership of a beautiful antique pocket watch and then smashing it to pieces to see how the insides worked.

This is a little unfair, because – as Lytollis himself notes – the savage cost-cuts implemented by Newsquest kept the group alive. Perhaps there was no other way.

But then again I have to question the priorities of a company that cuts its way out of trouble by sacking its best staff, not least Lytollis himself. For evidence of his writing ability look no further than the fact that in a world in which journalist memoirs are ten a penny, and normally self-published, his has been released by major publisher Little, Brown.

Why would a business built on people reading words sack its best wordsmiths (and feature writers are hardly the biggest burden on the wage bill)?

The answer is provided by Lytollis himself. If you measure success with online clicks then there is an argument for phasing out the gourmet meal lovingly prepared by the likes of Lytollis in favour of the journalistic equivalent of a flipped burger.

He noted that one week he spent hours crafting a profile of an author, and ten minutes rewriting a press release about a former footballer’s hair transplant. The press release received 125-times the amount of online hits.

His book resonated particularly for me because Lytollis started in local newspapers in the mid-1990s, just a few years before I did, and he depicts a world I can almost recognise.

I say almost because I worked at Johnston Press and Newsquest, two publishers who made massive levels of profit up to 2008 by cutting local newspapers to the bone before such tactics were strictly necessary for survival.

CN Group was different

The newspaper group Lytollis began his career at was different.

Owned by the Burgess family, CN Group continued to invest in local journalism long after this stopped being fashionable. As a result, its titles would regularly sweep the board at the Regional Press Awards. In a world of declining standards, CN Group could still be relied upon to do local newspaper journalism well.

Lytollis reckons that pre-2008 there were at least 64 journalists manning CN Group’s two titles: the daily News and Star (a punchy tabloid) and weekly Cumberland News (a handsome broadsheet). At the point he left, in 2019, he says there were 15 left (most of them trainees).

Carlisle-based CN Group went from a newsroom with centuries of experience and knowledge to one “staffed primarily by transient, overworked, underpaid journalists, who are either trainees or recently qualified” post the Newsquest take-over, according to the NUJ.

Those heading for the exit post-2018 included (according to Lytollis):

- Hard-working editor Chris Story who “did the meetings aspect of the job [which dominated the days of his predecessors] while also writing and subbing much of our papers”

- All the photographers bar one

- All the sub-editors except one

- All three feature writers (including Lytollis himself).

Journalist and Author Roger Lytollis from Carlisle Cumbria. Roger is the author of Panic as Man Burns Crumpets: The Vanishing World of the Local Journalist: 11 July 2020. Stuart Walker Photography 2020

Circulation of the daily News & Star fell from 26,000 in 2005 to less than 6,000 per day in 2019 when Lytollis left, he says.

Advertising revenue fell off a cliff following the economic crash of 2008, and when it returned it went largely to low-cost online competitors like Google and Facebook – who together take more than half all the money now spent on advertising in the UK.

Localised versions of these twin disasters hit every local newspaper in the UK.

But reading Lytollis’s insider account of the decline of CN Group you have to question some of the decisions that were made along the way.

Facebook vitriol

Putting links to stories on the News & Star Facebook page just seemed to open up journalists to vitriol, Lytollis notes.

“Our Facebook policy was geared towards increasing engagement with readers. As far as I could see, this consisted largely of them telling us we were crap…

“A story about an open day at Carlisle’s mosque prompted so many offensive comments that we removed it from Facebook. Facebook made a fortune from advertisers using it to reach people who read journalists’ work there. But the company did little to deal with inflammatory reaction from its users. Newspapers’ Facebook pages were the journalistic Wild West.”

As newspaper sales dropped by 10% a year CN Group cut costs and increased cover price.

Charging ever more for an inferior product does not look like a great long-term business strategy. Meanwhile, all the content was given away for free online despite the fact online ad revenue was nowhere near eclipsing print.

Like a sweet shop doubling its prices then running out into the street and throwing Mars bars at passers-by.

In 2017 CN Group ran an appeal asking readers for donations to help fund its journalism alongside the logo “No to fake news”.

“Asking our readers to pay for something we were giving away seemed a desperate idea,” says Lytollis.

Two weeks after the “No to fake news” logo appeared, the News and Star sold its front page to the Conservative Party. Days before the General Election, the advertorial headline read: “On Thursday: Vote to get Brexit Right,” alongside a picture of Prime Minister Theresa May.

This was pre-Newsquest, but was a tactic repeated in the Newsquest era and which prompted a savage backlash from readers.

Lytollis writes: “Newsquest had the resources to improve CN Group’s papers and websites. But its strategy seemed to be to cut costs enough every year to still make a profit. You can do that for only so long until there’s nothing left to cut.

“The message that everything should go on our website was reinforced daily. Every story, however small. Every columnist. Even the horoscopes. I’d think, please, can you leave people with some reason to buy the paper.”

The hunt for clicks

He questioned the point of running national stories under the WEIRD UK NEWS section on the website to chase online clicks.

“At one point the most-read stories were:

1. Thomas Cook fears going bust…

2.The seven medical conditions you MUST tell the DVLA about

3. Asteroid the size of a skyscraper due to pass by Earth.”

I’ve seen this audience-chasing non-local stuff endlessly defended as a way of subsidising more traditional public service news, but in my book journalists are in the relevance business more than the reach one.

A sustainable future lies with repeatedly providing target readers (the ones advertisers will pay a premium to reach) with useful, relevant information which they can’t find anywhere else – not with viral hits clicked on by anonymous drive-bys.

Lytollis notes that his own redundancy notice arrived just days after Newsquest received a grant from Google for a project making it easier for non-journalists to provide news and features to the company free of charge.

A glance on the News and Star website today shows plenty of quality journalism on there to enjoy from the mainly young newsroom team and some remaining veterans. Chief reporter Phil Coleman was shortlisted for the national Paul Foot Award in 2019 after his investigation led to the arrest of a fake doctor who worked in the UK for 22 years without qualifications.

The most-read stories on the News & Star at the time of writing look like a healthy mix of hard news and local issues.

In the good old days when print paid the wages of huge newsrooms, it also led to a certain space-filling mentality which is perhaps less likely now when every story is scrutinised for clicks. How many readers look at all those vox-pops, nibs and fence-sitting leader columns I wonder?

But in Cumbria and around the UK we have allowed something beautiful to be destroyed. Local newspapers at their best are machines for binding communities together, sharing local knowledge and fighting for the rights of ordinary people by providing them with a voice and demanding answers on their account.

I remember covering local council meetings and court cases, quizzing developers about controversial plans and speaking to bereaved families about the avoidable deaths of loved ones when I was a junior reporter (and the only reporter on my little weekly). I marvelled that this vital watchdog role was being entrusted to a fresh graduate who did not know his journalistic arse from his elbow.

I was paid £8,000 a year in 1998 (less than today’s minimum wage when adjusted for inflation). It was clear that Johnston Press cared more about maintaining its then 40% profit margin than it did about paying a wage that would provide the communities it served with experienced newsroom professionals.

Sadly the picture has deteriorated since then. Patch reporting has gone out of the window in some places, with pools of reporters instead filing stories for multiple titles across a vast area that they rarely visit.

Thankfully this is not the case everywhere. And I take my hat off to the thousands of local newspaper/website reporters around the UK who continue to wear their shoe leather out performing a vital watchdog role in their communities.

And there are signs that the ship is now turning around.

Regional press giants Reach and JPI Media are expanding.

Whilst the Lytollis story has a sad ending, he’s not bitter reflecting that: “Journalism had given me access to the famous and the powerful, to ordinary people with extraordinary stories. It had taken me to places I would never have known. It had given me everything, satisfaction, confidence, partners, friends, a living, a life.

“I’d always loved the job. For all its stresses, it lifted me more than it weighed me down.”

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog