New national newspaper launches don’t appear out of thin air. Even if they only take nine days, which was the case with The New European – a ‘pop-up publication’ launched by my company, Archant, in the aftermath of the UK’s Brexit vote.

June 24 was a shocking day, whichever way you voted in the referendum on Britain’s future in the European Union. Many people had gone to bed the night of the vote believing the Remain campaign were on track to victory. UKIP leader Nigel Farage had even conceded defeat.

So when the vote went the other way, and by a relatively tight margin, millions of people were left feeling stunned that such an historic decision had gone against them. The sense of dismay in many parts of the country – those parts marked out in vivid yellow on the graphics plastered across all of our TV news channels – was palpable.

That Sunday, I received an email from Matt Kelly, the chief content officer I’d recruited to Archant the previous November. The email read:

“Jeff, I realise this will sound a little crazy but if ever there was a perfect time to launch a new national newspaper, this is it. There are 16.5m people out there feeling really hacked off and I can’t think of any newspaper that properly represents that sense of anger many of them are feeling. A pro-European newspaper for the 48%. Wdyt?”

What did I think?

I thought he was right; it did sound a little crazy. Launching newspapers is usually a long, expensive and very challenging process.

In very recent history, there were at least two other brave efforts that had bitten the dust prematurely; Trinity Mirror’s The New Day and Cumberland News’ 24. It was the kind of environment that would make any chief executive think very carefully.

But he was also right about the opportunity. The 48 per cent was both a clearly identifiable and very passionate audience. We even knew exactly where they were to be found; the referendum data gave us the perfect distribution map.

Plus, it was true there had been newspaper launches in the recent years which had managed to carve a new space in what might have seemed to be an impossibly crowded market, The i in particular.

Of course there were dozens of outstanding questions but I was keen to hear more and perhaps use this idea as a counterbalance to what promised to be a rather sober senior executive meeting that Tuesday as we discussed the potential downsides of Brexit for the media industry.

“Not crazy,” I replied. “Bring it up at the exec and let’s discuss.”

As it happened, Matt almost forgot to bring the idea up on the Tuesday executive meeting. I think we were all wallowing in a morbid expectation Brexit was going to make a tough industry even tougher.

Finally, after a couple of hours of prudent consideration and planning for potential downsides, I looked around the table and asked if anyone had any positive thoughts. This was Matt’s cue, and his idea had evolved since the weekend.

![]() It would be a paper with a very limited shelf-life, published into the zeitgeist of interest Brexit had stirred up. We described this new formula for print launches as ‘pop-up publishing’, turning the traditional recipe of high-cost research and development followed by a massive launch advertising campaign entirely on its head. This, instead, would be agile, low-cost, and with an elegant exit baked into the plan.

It would be a paper with a very limited shelf-life, published into the zeitgeist of interest Brexit had stirred up. We described this new formula for print launches as ‘pop-up publishing’, turning the traditional recipe of high-cost research and development followed by a massive launch advertising campaign entirely on its head. This, instead, would be agile, low-cost, and with an elegant exit baked into the plan.

It would not be a website. Instead, and totally counter to the perceived wisdom of digital-first, we’d focus on establishing it in print.

After all, who would care or even notice if we launched a website? And who would pay for it?

It would be a blend of serious Brexit debate and news and also the lighter, more fun cultural side of Europe. Every word in it would be original and focussed on the great things that bring us together as European. One thing it would not be, Matt was keen to point out, was party political.

“The whole point is the 48 per cent isn’t aligned to any one party. That’s why there’s no newspaper there for them today,” he argued.

This was an important consideration since Archant has a long and proud history of not taking political sides editorially. We like to give our community of readers the facts and assume they are smart enough to make decisions themselves. Framed that way, as transcending party politics, this new newspaper fitted that mandate perfectly.

The business case would be centred around cover price. Given we had very recently seen the public’s unwillingness to fork out 50p for a new newspaper, the proposed cover price of £2 seemed bold. But both Will Hattam, our chief marketing officer, and Matt seemed sold on the idea this would be a high quality product people would want to carry around like a badge of honour.

Cover price was not going to be the thing which made or broke The New European. How close we could get to articulating the emotions of the Remain camp would be the deciding factor.

If Matt or I were expecting the room to push back against this prospect of launching a national newspaper (unknown territory for us as a leading local newspaper and magazine business), we had no reason to worry. Everyone instantly got the idea and saw the potential.

Enthusiasm for the project grew quickly as we talked through how we would overcome what might seem, traditionally, to be significant barriers.

At Archant we have a very talented team of in-house designers and Matt leads a team of 500 or so journalists. He also had a fantastic contacts book with some of the best writers and thinkers in the UK, having spent 20 years in national newspapers. So we had enough content resource to make it happen. But what about distribution? What about marketing? What about selling advertising?

All these important and challenging questions were compounded by a single, looming reality; if we were going to do this, we had to be quick. The point about zeitgeists is they disappear as quickly as they surface.

Today’s zeitgeist is tomorrow’s fish and chip paper (or was, at least, until the EU outlawed wrapping chips in newsprint for health reasons).

We agreed, given the clear impossibility of launching a new newspaper in three days flat, we would still have to aim for a launch the following Friday if we were to have maximum impact. This was late Tuesday afternoon. We were talking about a launch date nine days away. Was that even possible?

Even with a fair wind and the necessary expertise and infrastructure, the idea of designing and filling a new newspaper with terrific original content, then getting it printed, then distributing it and marketing it nationwide was daunting to say the least. But as I looked around the table I did some mental maths. The seven senior executives who comprise One Archant’s management team had close to 150 years of industry experience between us. If anyone could do it, this team could.

Will was confident in his team’s ability to deliver, which was good enough for me. His head of circulation, Darron McCloughlin, was sure he could arrange a national distribution network in time. Nick Schiller, our group operations director, arranged a quickfire deal with the Guardian to use their Berliner-format presses and publish The New European in that most continental of formats.

But perhaps it was Craig Nayman, our chief commercial officer, who had the tallest order, selling advertising into a newspaper nobody had ever seen, with a circulation nobody could know and with a polarised audience which might deter some brands. In the event, it was job he managed to carry off and The New European had paid-for advertisers from day one and continues to attract premium rates in the market.

The next day we talked through a business case put together quickly by the finance team. Even without advertising, the commercial proposition seemed strong. Given we weren’t going to have an advertising campaign, instead using our marketing team and to generate PR opportunities and spread the word, the project had a remarkably low circulation target to achieve break-even. Not only did it feel like an exciting new newspaper. It felt like an exciting new publishing model.

I decided on the spot to greenlight it. It was definitely worth a punt. Even if the paper did not sell, I was happy the process would be great for us as a team. We would learn new things and take confidence from our ability to innovate and challenge the perceived wisdoms.

The fact it was a print project and not digital, which, like all legacy media businesses is a platform we are constantly developing, only seemed to add value to it. It was, in many ways, completely counter intuitive. This was a project very few businesses in the country could undertake. And even fewer, perhaps only one, actually would.

After a last minute wobble on price – we debated the benefits of a cheaper £1 – we resolved on a £2 price, and a large initial run to be printed by the Guardian presses in London and Manchester. We also decided we would only commit to an initial four issues, in keeping with the idea of pop-up publishing. In hindsight, this was the best decision we made in the entire project. Knowing this ‘pop-up publication’ was only designed for a very short life liberated us from all the typical attendant anxieties and risks associated with a venture of this size.

There was only one thing left. The name. It’s called ‘The New European’, Matt said.

It may have sounded like the title of an Ultravox album from the 1980s but seemed to fit perfectly the spirit of adventure and optimism we had in mind. And it demonstrated yet another great benefit of pop-up publishing; no time to dilly-dally about with dozens of alternatives and weeks or months of market research. No time to let yourself be talked out of the first idea, the idea that got the project started in the first place.

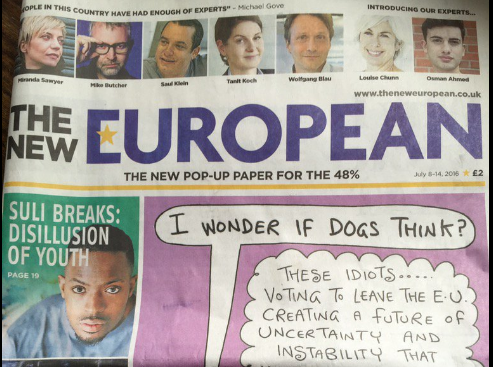

So that was it. The New European and pop-up publishing were born. Then the work really began. Our first issue featured articles from Jonathan Freedland, Miranda Sawyer, James Brown plus Tanit Koch, the editor-in-chief of Europe’s biggest selling newspaper, Germany’s Bild, Wolfgang Blau, the Conde Nast digital boss, and Peter Bale, CEO of the Centre for Public Integrity.

On its very distinctive front page, there was a large cartoon from Private Eye cartoonists Kerber and Black in which a dog’s owners idly wondered aloud if their pet could think.

The thought-bubble above the dopey-looking dog’s head read: “These idiots… voting to leave the EU, creating a future of uncertainty and instability that will have a knock-on effect for generations to come… leading to isolation and beleaguerment for this once great nation!!!”

It seemed to capture very well the blend of seriousness and irreverent humour that has since characterised the paper.

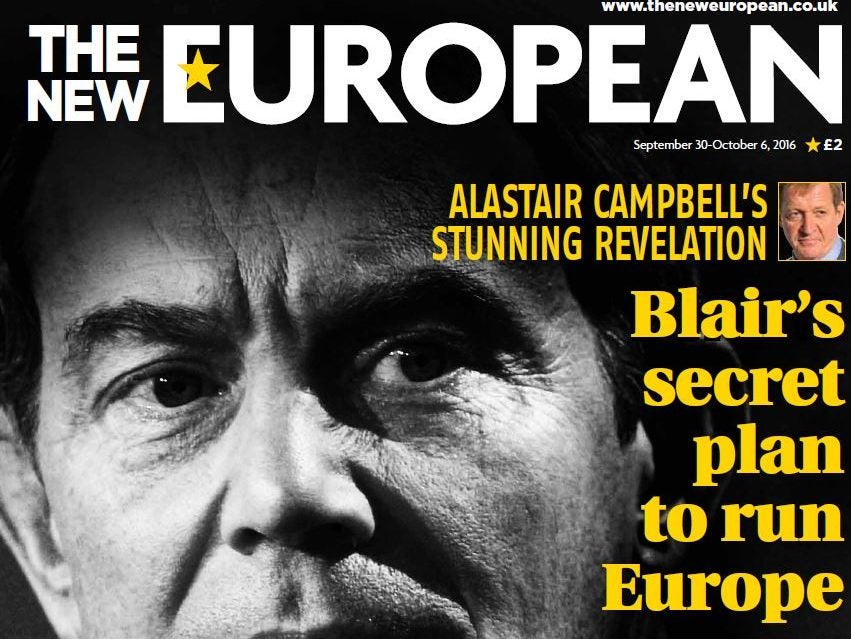

The paper’s launch attracted considerable interest from other media, even within the crammed news agenda of post-Brexit. The Archant team were interviewed dozens of times, and had appearances on Sky’s Ian King Live and the BBC’s Daily Politics show with Andrew Neil, besides plenty of radio and press appearances. The striking design of the paper was deliberately bold and the front pages had the feel of great posters. There’s really nothing quite like it in the UK market and it really stands out on the newsstand.

Another satisfying aspect of The New European is, although plenty of people disagree with what it stands for, hardly anyone has criticised it as a product.

In fact quite the reverse – critics from media as varied as Mashable, Business Insider, The New York Times and The Guardian have showered it with praise. Mario Garcia, the world’s leading newspaper designer, dedicated an entire blog post to it. If people knew the entire design was conceived in a single afternoon, and the masthead itself in less than 20 minutes, it could seriously undermine the business of every media design agency in the western hemisphere!

But aside from the quality of the paper itself, it’s perhaps the miracle of distribution that was the deciding factor in The New European’s success.

No point having the greatest new newspaper in recent years if you can’t get it to the shelves. That first week, Archant’s circulation team managed to have copies on sale in more than 20,000 shops, supermarkets and garages. As I’m writing this, on the eve of Issue 12 (who’da thought it!) that figure is now more than 40,000 retailers in the UK plus outlets throughout the Republic of Ireland, France, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium and Luxembourg.

For me, this was the most satisfying aspect of The New European story; the strategy of One Archant had created an environment in which this was achievable. Previously it would have been unthinkable, and actually laughable, to think we could have pulled this off.

That first week, we sold more than 40,000 copies. And although sales dipped in the dog days of August, in September we have seen three consecutive weeks of circulation rises.

Every single issue has been profitable. That in itself is an almost absurd achievement.

The quality of the paper seems to have got better and better. Contributors to date include Sir Richard Branson, who interrupted his birthday holiday in Necker to write a lead piece for us and then widely praised Archant for the way we’d seized the opportunity, Alastair Campbell, the leading philosopher AC Grayling, Dylan Jones, Hardeep Singh-Kholi, Parmy Olson, Patience Wheatcroft, Bonnie Greer, Nick Clegg, Chuka Umunna, Simon Barnes, Will Self, Howard Jacobson, to name just a few.

Paul Morley’s three-week-long articles on David Bowie’s European years made for some fabulously striking covers and Issue 11’s five-page investigation into how mainstream press had covered the issue of migration before the Referendum won the paper a hugely positive response on social media, and quite a few hardcore Brexit haters as well.

One observation leveled at The New European, though, is it’s a one-off, the product of a near-perfect alignment of events which opened up the space for such a new product. And so, the argument goes, while Archant deserves great credit for spotting and seizing the moment, it’s not necessarily a repeatable trick.

I disagree. I think pop-up publishing, as a model for launching new print products, is a sensible response to a world hungry for in-depth coverage on certain topics but for only a limited period of time.

As a content proposition it’s well-suited to our fast-moving world.

As a business model it’s a low-cost, low-risk model which allows for experimentation and dramatically caps the exposure for the business should it turn out we’d got the idea hopelessly wrong. One thing is certain. We were not hopelessly wrong with The New European.

I believe The New European will continue to evolve in shape and form. We will need to think hard about what is the right digital presence for the brand since there is clearly an affection and demand for it. But we should also think beyond that – events, magazines, merchandising. We now print on a rolling four-week basis, but should demand for the newspaper fall away there’s no reason why the brand won’t carry through to another platform.

Ultimately, that’s the beauty of pop-up publishing. You never quite know where you’re going to pop-up next. For instance, we’ve already designed and sold hundreds of mugs and t-shirts bearing the image of that cartoon dog from the very first issue, which has appeared each week in the Kerber and Black cartoon. We’ve even given him a name. Rexit. Turns out he’s not so dopey after all.

Jeff Henry is CEO of Archant, publisher of the New European.

This essay is taken from: Last Words? How Can Journalism Survive the Decline of Print? Edited by John Mair, Tor Clark, Neil Fowler, Raymond Snoddy and Richard Tait Abramis Academic Publishing Bury St Edmunds £19.95. January 2017. Available at special pre-publication price of £15 to Press Gazette readers from Richard@abramis.co.uk

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog